Body and Soul

Broadening the Focus on Gay and Lesbian Health

|

Things would be much easier if that proverbial apple a day really did keep the doctor away. But getting and staying healthy is, of course, much more complicated, even for those with healthy diets.

Things get even more complicated when sexual orientation gets added to the health mix.

Gay and lesbian health issues often seem to be driven by a crisis mentality, and for some valid reasons. AIDS devastated the community during the eighties and early nineties, demanding an urgency until then unknown in community-based health responses. The success of that response has been proven in clinical advances in the treatment of HIV, although AIDS remains one of the most important challenges facing the gay community, as infection rates threaten to take off again among a new generation of gay men.

But the challenges that remain don’t negate the successes achieved. And as the long-term effects of that success make themselves more and more apparent — longer lives for those with HIV and advances in stopping the spread of the virus — the broader range of health issues facing the gay and lesbian community come more into focus.

Many of the health issues facing gays and lesbians aren’t perceived as crises in the community — they may, in fact, seem mundane. We know about cancer, after all — the media are full of reports and studies on what causes cancer and what may prevent it. Why should gays and lesbians be any more concerned about cancer than our straight friends and family?

But if you’re gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, you may be at higher risks for some types of cancer. Gays and lesbians also have higher rates of smoking than the nation at large, and alcohol and substance abuse continue to cause both physical and mental health problems for large portions of the community.

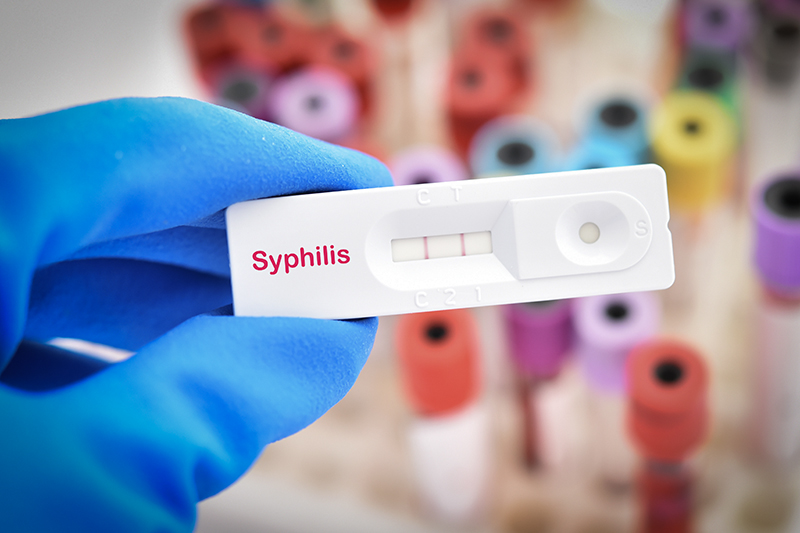

Lately, the community focus has been on antibiotic resistant staph infections, more accurately known as Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MSRA). Recently, doctors in Los Angeles reported seeing an unusual number of gay men with MSRA infections. Not long after, MSRA infections were found in gay men in other major cities, including a handful of cases in Washington, D.C.

Because MSRA, and staph bacteria in general, are transmitted primarily by skin to skin contact, the appearance of the infections among gay men has caused much speculation about the possible emergence of a new sexually transmitted disease.

“I’ve seen a fair amount of what I call low-grade panic, ” says Dr. Doug Ward, who has treated some of the D.C. cases. “Epidemiologically, it’s upsetting if it’s getting into the [gay] community. ”

But Ward says much of concern, while understandable, is misplaced.

Everyone has staph bacteria present on their skin. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 25 to 30 percent of the U.S. population is colonized with staph bacteria in the nose. In addition to skin-to-skin transmission, the possibility of nasal colonization — basically, the presence of staph in the nose without causing infection — has led to warnings about not sharing bullets and other items used to inhale drugs such as cocaine and crystal meth.

An MSRA infection can cause deep and painful sores, and in some rare cases lead to serious blood infection and other life threatening problems. MSRA is resistant to the penicillin-related antibiotics generally used to treat common staph infections, but it is still treatable with other antibiotics.

“It’s a nasty thing, and somewhat more difficult to treat, ” says Ward. “[But] if you don’t sit around worrying about getting a staph infection, then you shouldn’t worry about getting an MSRA infection. ”

While much worry about staph infections has centered on gay men and possible sexual transmission — and actual transmission routes for most of the cases have not been determined — the larger concern would actually be one that doctors and medical professionals have been warning the public about for years now: the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, which leads to resistant strains of many disease causing bacteria. Many fear that the development of resistant bacteria may soon outpace the development of new antibiotics.

So what, then, are health issues for gays and lesbians? In many ways, our health concerns mirror those of the straight community. Cancer, for example, can strike almost anyone, regardless of age, gender or sexual orientation. But just as age and gender can impact how and when cancer strikes, sexual orientation can impact how cancer strikes in our communities.

Sunday, March 16, marks the start of the National Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Health Awareness Week. Sponsored by the National Coalition for LGBT Health, the week aims to highlight some of the most pressing health issues facing the community. Some of them are familiar, some perhaps not — but all of them are important aspects for a healthy community.

SLOW BURN

|

For a smoker, lighting up is as natural as flushing the toilet or hitting the snooze button. The decision to have a cigarette hardly even occurs — one minute you’re just breathing, and the next, you’re inhaling. But if you’re gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, your nicotine fix may be more entwined with your sexual orientation than you think, according to some GLBT health care providers.

“When people come out, it’s a major influence in their lives, ” says Kathleen DeBold, executive director of the Mautner Project for Lesbians with Cancer. DeBold highlights the bar-centric lifestyle that many gays and lesbians find themselves in, where smoking always seems to be just an arm’s length away.

A 2001 Harris Interactive/Witeck-Combs Communications study found that over a third of gays and lesbians smoke, compared with one-quarter of all adults. And a 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey conducted by the CDC estimated that the number of gay youth who smoke is nearly double that of straight youth.

This “niche market ” status has earned the gay community a special place in the ad campaigns of tobacco company marketers, who have increased their “outreach ” efforts with ads designed with the gay market in mind.

“Lucky Strike has an ad with the tagline, ‘When you hear the word fag, we’ll be there.’ Like they’re behind us or something, ” says DeBold. “It’s ironic, because cigarette companies are one of the biggest contributors to the radical right. ”

Image creation has long been the forte of tobacco companies, which created the Marlboro Man in the 1950s to counter the feminine status ascribed to filter cigarettes. The Marlboro Man was just the baseline step toward today’s ultra-savvy cigarette ad campaigns.

“Cigarettes are marketed to fit any attitude, ” says DeBold. “If you’re femme, it makes you sexy. If you’re butch, it makes you tough. If you’re a queen, it gives you that bitchy, sassy, queeny persona. You want to fit in? It can do that for you. You want to rebel and be an outsider? It does that too. Smoking is one size fits all, and every size is bad for you. ”

To counter gay-specific tobacco marketing efforts, some groups have created gay-specific smoking cessation programs aimed at helping gays and lesbians quit with a support group they can relate to.

“The response from our clients is, ‘I can talk freely about my life here,’ ” says Mary Beth Flournoy, clinical program manager and head of the smoking cessation program at Whitman-Walker Clinic. “There’s an openness and humor about it that comes naturally with the gay community. ”

For instance, at the meetings, people can feel free to talk about how to deal with smoking in gay bars without worrying that someone in the group will be made to feel uncomfortable.

Whitman-Walker’s smoking cessation program consists of seven sessions over the course of six weeks. The first two weeks focus on preparation and education as clients find quit buddies, examine why they want to quit smoking and psych themselves up for the final drag. The “quit ceremony ” takes place in the third week, when everyone publicly throws away their cigarettes. The remaining weeks are filled with relaxation techniques, discussions with health experts and dealing with any relapses.

“In the old days, they’d show you pictures of black lungs, ” says Flournoy. “Today, most people know about that. We don’t do the gruesome stuff so much, and we don’t send the ‘You smoke so you’re bad’ message. ”

Another classic misconception, according to Flournoy, is the “quitting by epiphany ” theory. The average smoker tries to quit six or seven times before being successful, she says.

“We encourage [our clients] to sit down and look at why their previous quits didn’t work. Figure out what your hardest cigarettes are, which ones you need the most, and work on those. ”

The Mautner Project has also run a smoking cessation program since 1990. Both programs are open to any type of technique that helps people quit, including recently popularized prescription drugs like Zyban and Wellbutrin. Their thinking is that no possible harm that these drugs can do is worse than smoking.

“Some people can go cold turkey, some people need the drug, ” says DeBold. “Whatever works. ”

DeBold suggests that one reason gay people have such a hard time quitting is because of the constant tsk-tsking that society projects toward gay life in general, turning the right to smoke into a last stand.

“We react very defensively toward ‘do not smoke’ messages because we’re persecuted already, ” she says. “Society is always saying, ‘don’t be gay, don’t be lesbian,’ so when someone finally says ‘don’t smoke,’ most people react with a ‘fuck you.’ ”

DeBold has also encountered clients who feel that being gay comes with enough baggage to justify smoking. Between homophobia-inspired layoffs, familial alienation, the Christian Right and staph infections, why not light up if it helps you relax and escape for a moment?

“That’s a question that makes our work very hard, ” she says. “What we try to emphasize is that smoking kills more gay people than AIDS, than hate crimes, than breast cancer. It’s a true killer, and we’re glad that it’s finally on the radar. ”

CHECKING CANCER

|

There was a time when HIV was called gay cancer. We now know that this is not the case, and that no cancer is wholly confined to a specific segment of the population. But neither is cancer completely blind to sexual orientation, a fact that has gained an increasing amount of attention within the medical community.

“People are becoming more aware and open to cancer screening, ” says local physician Doug Ward. “The recommendations we make to gays and lesbians are similar to those for everyone. For women, breast and cervical screening. For men, prostate screening. ”

Ward cites prostate cancer as the biggest concern for HIV-negative gay men. He recommends that anyone over the age of forty get screened, which involves a rectal exam and a blood test. African-Americans and those with a family history should get screened earlier.

A particular concern of Ward’s is the increasing number of gay men for whom the gym is church and anabolic steroids communion — the use of which can increase the risk of prostate cancer as well.

“Anyone who’s using steroids or testosterone supplements absolutely needs to be concerned about that. ”

Cancer is also a concern for the gay community because of the prevalence of one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases, Human Papillomavirus(HPV). Current estimates by the CDC and others are that among sexually active adults age 25 to 30, up to three-quarters carry some form of HPV. The most commonly known form of HPV is genital warts. However, there are up to 100 different strains of HPV, some of which cause warts and others that cause cancer.

Dr. Philippe Shiliade, Whitman-Walker Clinic’s Medical Director, says that the most frequently seen form of HPV among gay men is genital warts, which are typically removed by freezing or burning. They can also be infected with strains of the virus that cause cancer, which is one of the reasons many medical groups have begun recommending that gay men undergo regular pap smears to screen for anal cancer.

“The risk of anal cancer in the general population is small, ” says Shiliade, but that risk goes up significantly for men who have sex with men. He recommends that HIV-negative gay men who have receptive anal sex receive a pap smear every two to three years; HIV-positive men should have them every year.

Although many specialists are recommending these regular screenings, the recommendations are not universal. Though studies indicate that the disease is on the rise, Ward cautions against a panic.

“In all honesty, ” he says, “I’ve been doing this for fifteen years and have only seen two cases of anal cancer, and both were in patients with very advanced HIV. ”

The problem with anal pap smears, says Ward, is that even if they do turn up a precancerous legion, there’s little that can be done except to keep a close eye on it.

“With cervical pap smears, there’s a well-established protocol of what to do, ” he says. “I’ve sent patients with precancerous anal lesions to a rectal surgeon and the response is, ‘Why did you send this patient to me?’ ”

Gay men who receive anal pap smears may also find that health insurance plans may not cover the tests, at least until further studies show a more definitive preventive link between the tests and increased anal cancer rates.

While gay men are facing increases concerns about anal cancer, lesbians have been told to be on heightened alert for possibly high rates of breast cancer. Ellen Kahn, Director of Lesbian Services at Whitman-Walker Clinic, urges lesbians to balance concern about breast cancer with caution against hysteria.

“There was a lot of attention given to breast cancer in the lesbian community several years back, ” she says. “If you look back at that research now, you can see that it wasn’t always scientifically sound. ”

Kahn points out that the lesbian community was much more bar-centered twenty years ago, and as a result, those women were more likely to drink, smoke and to be overweight — all of which increase the risks for breast cancer.

“It was also much earlier in the liberation of the queer community, ” she says, “before people began to take better care of themselves and feel valued as members of society. ”

Barbara Lewis, a physicians assistant at Whitman-Walker Clinic, agrees.

“In a lot of the lesbian community nowadays, it’s not so cool to drink at all, ” she says.

Regardless, breast cancer remains the biggest cancer risk for lesbians. The reason, both women feel, is a general reluctance to get screened. Kahn postulates that there isn’t “effective communication targeting the women who partner with women community. ” The American Cancer Society recommends women begin monthly breast self-exams at age twenty.

Another concern is that lesbians are less likely to carry a child than most women, which puts them at a higher risk for ovarian cancer. One remedy that’s been suggested for this is to have lesbians take birth control pills, which trick the body into thinking it’s pregnant. Neither Kahn nor Lewis personally advise this, however.

“I wouldn’t put someone on the pill just for that, ” says Lewis. “There’s just too much we don’t know. ”

The misconception that lesbians are at no risk when it comes to cervical cancer is also being dispelled. HPV is the leading cause of cervical cancer. Since women who do not partner with men are less likely to acquire HPV, they have been dismissed as a low-to-no risk group in the past. But this doesn’t take into account the reality that some lesbians have had sex with at least one man at some point in their lives, as well as the fact that HPV can be transmitted by sharing sex toys.

“Physicians should not assume that women who have sex with women aren’t at risk, ” says Shiliade.

Abstinence, highly touted by conservative groups, is indeed the surest way of circumventing such cancer-causing STDs. In the case of HPV, safer sex practices such as condom use don’t necessarily block the spread of the virus, which can be present both on and around the genital and anal area. Still, many medical professionals deem an abstinence approach unrealistic.

“Yes, there is a risk of long-term predisposition to cancer [for those who have HPV] ” says Ward, “but that risk is still pretty low. Personally, I think recommending abstinence is going too far. ”

Thinking Healthy

In many ways, mental health has been a dominant issue in the modern LGBT movement. After all, it’s only been thirty years since the psychiatric establishment — in the form of the American Psychiatric Association — removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Over the past decade, research into depression, substance abuse and other issues have made mental health a pressing issue for the gay and lesbian community.

The National Coalition for LGBT Health says that members of the LGBT community have a higher incidence of mental health problems and stress-related disorders, including depression, eating disorders, anxiety, low self-esteem and substance abuse, with contributing factors that include social prejudice, internalized homophobia, discrimination and violence.

According to the Coalition, gay men report higher rates of depression, panic attacks and eating disorders than heterosexual men, while drug use, combined with low self-esteem, results in behavior that increases the risk of HIV transmission. Similarly, lesbians report higher rates of alcohol and drug dependence, and higher rates of depression and anxiety than heterosexual women.

LGBT youth, often faced with ostracism from family and friends when they admit their sexual orientation, are at a higher risk for suicide attempts than their heterosexual peers, according to multiple studies and surveys. They also experience feelings of self-hatred, depression and anxiety. Transgender prejudice is also “pervasive,” the Coalition says, contributing to inadequate training and experience for mental health professionals to properly serve transgender individuals in need of support services.

“[These issues] have been around for a long time,” says Anne Clements, director of mental health, addiction and day treatment services at Whitman-Walker. “Both anxiety and depression have been compounded — and perhaps have increased a great deal — with HIV. We still have a lot of people seeking help after getting an HIV-positive diagnosis, even though there are a lot of support groups out there and a lot of really good education programs. It’s an adjustment that people have a depressive reaction to.”

Isolation, though, is what Clements cites as the “biggest enemy” of gay and lesbian mental health.

“Being around people with your same issues can be very helpful,” Clements says. “Building a support network that’s not centered around the bars, drugs, or exclusively around sex, has a positive impact on people’s mental health.”

“There’s a lot of room for the development of more drug, alcohol and tobacco-free activities, ” Clements says. “But it all comes back to the individual. The more that individuals in the LGBT community talk about these things, the more educated and sophisticated the community gets, then the more it seeks a healthier, diverse life.”

Local gay psychiatrist Neill Williams finds the community’s focus on body image to be another burning issue for his gay and lesbian clientele.

“It really alienates a lot of people who can’t achieve those body ideals they’re seeing on TV and in newspapers and magazines,” Williams says. “It causes a lot of anxiety, depression and poor self-esteem.”

Williams recommends building self-esteem on qualities that are less externally-oriented, such as education and quality of friendships. “I’m also a big proponent of exercise,” he says. “[It’s] a great social outlet, a physical and mental outlet to deal with stress, and help prevent some of those depression and anxiety feelings from happening.”

“If you’re recognizing that you’re not feeling well,” Williams says, “you need to communicate that to friends and family. Often they’re able to be a sounding board and help you decide if you need to seek professional help.”

Local gay psychologist Michael Radkowsky, who treats mostly gay men and same-sex couples, encourages gays and lesbians to reject the stigma that’s often associated with addressing mental health.

“Seeking mental health treatment is a wonderful gift to yourself to heal and really be able to get the roadblocks in life out of the way,” Radkowsky says. “It’s unavoidable that any of us could have grown up in this society and not have negative feelings about ourselves, and not have been damaged in some way.”

Radkowsky finds that gays and lesbians grow up hiding sexual feelings, resulting in sexuality that develops separate from emotions. “That can make it really difficult to establish a relationship that includes being close with someone emotionally and being able to connect with them sexually,” he says.

“So much of what I see in my practice has to do with how we grow up and the negative messages that society continues to send us. We’re not allowed to marry. We just take that for granted, but it’s incredibly denigrating [to] feel that our relationships aren’t quite as good as everyone else’s.”

Despite having “a lot stacked against us,” Radkowsky points with optimism to the community’s ability to draw strength from its reaction to opposition and its resourcefulness in forging its own path without the clear-cut social landmarks that straight people enjoy.

“When you have to figure it out on your own,” he says, “you have a much greater sense of achievement because you didn’t just follow traditional ways of what’s acceptable. Instead, you can feel, ‘Wow, I did this journey on my own. I thought about what’s meaningful to me.'”

The Health Care You Deserve

|

But what you know about sexual orientation and health issues may not help you if you find yourself unable to take a critically important step in your own healthcare: Coming out to your physician as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. That means finding health care providers who understand LGBT health concerns and are free of the homophobia that can keep gays and lesbians from receiving necessary care.

Theo W. Hodge, Jr., is a gay physician who shares a Capitol Hill medical practice with another gay physician, Samuel Dotson. “Many of my patients have dealt with homophobic physicians,” Hodge says. “[Some doctors] have actually treated them poorly based on assumptions of sexual orientation and assumptions of perceived medical conditions, including HIV.”

Many gay and lesbian healthcare consumers seek out gay doctors, such as Dotson and Hodge, in an attempt to avoid the potential pitfalls of the straight-dominated medical establishment. However, says Hodge, that’s not necessarily the best way.

“If you have a gay or lesbian provider, it’s certainly something you might feel more comfortable with. But if you have a gay-friendly physician who’s well-versed in medicine, that will work just as well.”

More fundamental to your care is trusting your doctor enough to talk honestly about sexuality.

“It’s important to talk about your sexual orientation,” says Whitman-Walker’s Ellen Kahn. “And more importantly, to talk about your sexual behavior — regardless of how you identify — if you want the highest standard of care. If you don’t say, ‘This is who I am, and this is what my life is like,’ you can never get at that.”

Cheryl Fields, health education director for The Mautner Project, agrees.

“When you’re going to a provider with a lie,” Fields says, “and you’re trying to hide information because you’re afraid the physician will be homophobic or reject you, it’s very difficult to have an open conversation about anything.”

Fields recommends that LGBT people address their own comfort level with sexual disclosure and think about the issue before they go to their doctor.

“You don’t want to be in a situation where you’re in the room and the issue comes up, and then you’re panicked,” says Fields. “It’s better to have prepared for the conversation and assess how safe you are in having this conversation with your physician.”

Kahn says her office receives dozens of calls from women in search of physicians, nurse-midwives and dentists in the community who are lesbian-competent — a level of inquiry that Kahn finds “very promising.” Kahn has also seen an increasing number of women with HMOs and PPOs — plans that restrict members to a network of service providers — who are challenging their employers and health plan administrators who don’t address LGBT-competency and friendliness in the often-imposing directories employees must wade through to select a provider.

“People are becoming better advocates for themselves,” she says.

When choosing a provider, Hodge advises getting recommendations from gay and lesbian peers. You should also feel confident talking to doctors beforehand, either by phone or in a personal “meet-and-greet” interview, to gauge their responsiveness to gay and lesbian concerns.

“Sometimes you can walk into a waiting room and tell instantly if you’re going to be comfortable, ” says Hodge. “If you’re a young gay man, and you walk into a waiting room where everyone is a silver-haired 85-year-old, that’s a clue that the provider’s patient population is not going to be reflective of where you are.”

“If you take your health as a top priority, then you’re going to do things to ensure you live a healthy life, ” says Hodge. “[That means] being in a partnership with your physician. In any effective relationship, you have to have good communication, and if communication is hampered in any way because of the patient’s or physician’s discomfort, then you need to seek a new relationship.”

For more information about National LGBT Health Awareness Week, visit the National Coalition for LGBT Health at www.lgbthealth.net.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!