Common Ground

Interview with DJ Mandrill

Getting the bartender’s attention isn’t much of a problem at the Deep End. Except for a few stray patrons parked on the stools, the crowd seems determined to remain on the dance floor. The bass is so loud and so deep that even the flames of the tea lights are driven to dance, bounding up from their wicks with each dark, rhythmic thud. Though at first glance the clientele appears to be exclusively African-American, it gradually becomes apparent that the Deep End is more diverse than most people may expect.

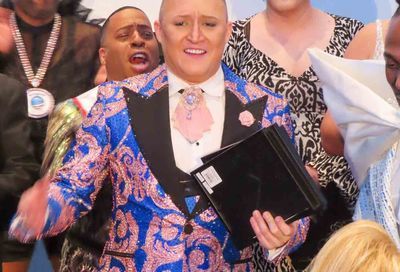

In a culture that prefers to view itself in simple black and white, DJ Mandrill has spent a career espousing the merits of thinking in shades of gray. His party, The Deep End, which celebrated its first anniversary on January 16, is where Mandrill tries to make that sentiment materialize.

“After twenty-two years of experience, I’ve found there’s a place in the middle, that gray area, that works,” he says.

But twenty-two years ago, Washington was a city without much to offer those seeking a middle ground. Dupont Circle was a place many gay black people felt unwelcome, forcing them to form their own scene independent of the area, and gay newspapers like the Washington Blade still largely ignored communities of color.

“I know 45-year-olds who still won’t read the Blade,” says Mandrill. “They don’t know that it’s changed. They only know that when they tried to pick it up way back then, they weren’t there.”

“It was pretty bad back in the Seventies,” he continues, recalling a time when clubs often made blacks of any age show three forms of ID, even as white adolescent twinks sporting peach-fuzz entered with hardly a second glance. “As culturally diverse as it is, mixing has always been very difficult. Washington tends to be very culture conscious and politically conservative.”

With the Deep End, Mandrill hoped to attract older gay black men, a demographic he sees as the most disenfranchised. His goal was to reestablish “the connection of the older teaching the new,” a passing on of legacy he feels is fading.

“A lot of people were saying to me, ‘You think you’re going to get 40-year-old men to go clubbing on a Wednesday?'” he laughs. “But so many bars cater to the younger audience. It makes people feel old, unwanted and insignificant. And what’s worse is the people in charge of those clubs are of that older age. It boggles the mind.”

Mandrill’s success in convincing middle-aged black men to abandon pragmatics and party on a work-night has not, however, overcome the unalterable fact that many older men are closeted and do not go to gay clubs. Helping these men come to terms with their sexuality may be something neither he, nor possibly anyone, can do anything about.

“I don’t think anyone is as homophobic as gay men,” he says. “But even more so, I don’t think anyone is as homophobic as black gay men. That’s an exaggeration, but in my experience in the black community, [homophobia] is overwhelming.”

Mandrill also points out that the perception that more blacks are closeted than whites is probably false, comparing it to the illusion that the welfare rolls are fully stocked with black teenage mothers of four. Therefore, he tries to make the Deep End neutral ground to encourage a motley crowd. To do this, he’s learned to take into account what the crowd wants to hear when choosing music, rather than simply play god at the turntables.

“You can’t just play brand new music and the stuff you like,” he says. “And you can’t just play what they want to hear, because you’re a jukebox if you do that. You’ve got to fall somewhere in between.”

Pushing the musical envelope is one more technique Mandrill uses to open people’s minds, forcing his audiences to at least sample something unfamiliar before they declare their distaste for it. It’s simply an extension of his philosophy for life. He does say, however, that he “no longer wants to shove music down people’s throats.”

As for those who get a little uneasy at the idea of attending a party where their color or gender may be a minority, Mandrill considers that even more reason to check it out.

“It’s important for people to put themselves in a space where they feel what other people, particularly people of color, have to deal with every day. It’s empowering.

“The way we grow, the way we change, the way we broaden our perspectives is by putting ourselves with who we are most uncomfortable.”

He pauses a moment, and then smiles, and like a doctor reassuring a patient about the size of the needle, adds, “It’s only uncomfortable for a minute.”

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!