Police Story

For Sgt. Brett Parson the GLBT police beat always comes back to the street

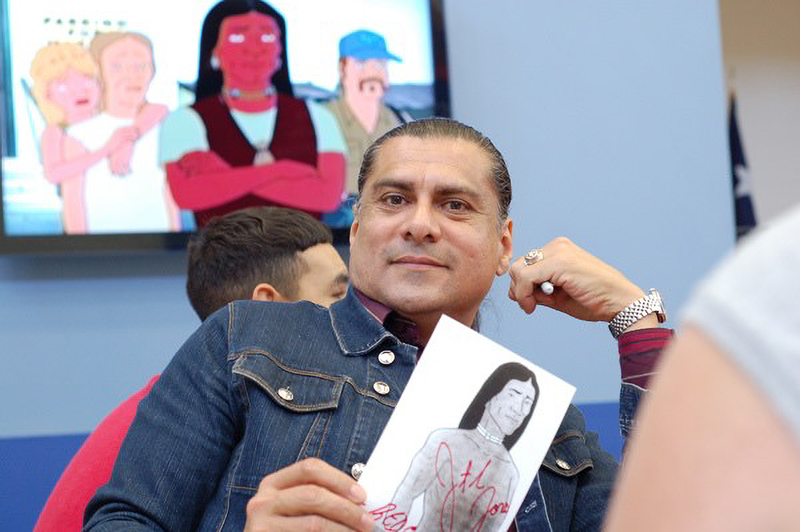

If you’ve been to even a handful of gay and lesbian community meetings in the D.C. metro area, chances are you’ve seen the jovial big guy with a badge, Sgt. Brett A. Parson. You may have seen him on Pennsylvania Avenue at Capital Pride. You probably saw him chatting with the crowd at the 17th Street High Heel Race.

Since 2001 when he became the head of the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department’s new Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit (GLLU), the city has had plenty of chances to see Parson as he tirelessly promoted the unit’s existence to the gay and lesbian community.

But even with all the public appearances he’s logged, perhaps the place you’ve seen him is the place he says he most wants to be — out on the street, being the cop he’s always wanted to be. A native Washingtonian, Parson exudes much of the tough guy aura you expect from a cop, from the burly build to the gruffly-told jokes. But as an openly gay police officer responsible for building the bridge between the police and a sometimes wary GLBT community, he’s built a reputation that’s well beyond stereotypes.

|

He came out to himself during his sophomore year at the University of Maryland, when a speech by an out gay athlete set off an epiphany. ” It finally hit me what I was,” he says. “I knew I was different than all the other kids. Now I finally had a word for it.”

Although he had always wanted to be a cop, his love of hockey for a few years took him across the country as a professional referee with the National Hockey League. His experiences there were highlighted in Dan Woog’s Jocks: True Stories of America’s Gay Male Athletes. Although he left the NHL in 1992 to pursue a law enforcement career, his coming out sports story was better accepted than one might expect, with “95 percent of the people” being accepting.

“I think I’ve had this fantasy story,” he says. “I haven’t had any nightmares.”

Parson’s experience as a gay man in the police department has followed much the same course, and lends to the straightforward approach he takes in his work. In its few years of existence, the GLLU has grown both in its presence within the GLBT community and in its role within the police department. On March 11, the unit opened its new office on Dupont Circle, a milestone for both the MPD and the gay community.

“I’d like to think it’s my take-charge attitude and my ability to lead, but I actually think it’s more my sensitive side,” he says of his success with GLLU. “And to some extent…my internal martyrdom. I’m not afraid to die for anybody else. I take that as an honor to have to do that, and I’m not afraid to do what I have to do to protect someone else.”

METRO WEEKLY: Tell me about the office in Dupont Circle and what its purpose is.

BRETT PARSON: It is definitely not a station or a substation. When people hear the words “station” or “substation” the assumption is that there is a full-service police [operation] and this is not that. This is exactly what it sounds like — it’s an office, a place where we hang our hats, where we have desks, where we keep our paperwork and things. We want this to be a place where when we are there, people feel comfortable dropping by, saying “hello.” We do not want this to become a location where people go when they are in crisis — the first thing you should do is dial 911. Don’t come to us, we’ll come to you — that’s the reason they give us those fancy lights and everything. But we’ll certainly schedule meetings there and hopefully it will become a focus of the community.

MW: How many people are involved in the Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit?

PARSON: The staff is 12 right now. Four of us are full-time police officers. The additional eight people that make up my staff are civilian volunteers, including four reserve police officers, who are trained and have limited police powers and wear a uniform. Then four police auxiliaries, who are citizens just like you or some other citizen who donate their time and expertise to the police department.

MW: What’s different about being a police officer and being a police officer in the GLLU?

PARSON: The first thing I want to do is turn that question around and tell you what’s not different. We’re police officers just like any other police officers in D.C., with full jurisdiction and full investigative authority and arrest powers. We specialize in dealing with the GLBT community. Other police officers may be assigned to the sex offense branch, the check and fraud unit, or school resource officers — they each have a specialty and when issues come up in that particular subject area, they are called upon to assist. That’s what we do in GLLU. We specialize in dealing with a community that has been traditionally under-served, disrespected and discriminated against. There are many ways that we serve that community, and probably the most important is that we do not just focus exclusively on community relations. We do general policing.

When I took over this unit in 2001, one of many demands I had was that this unit not be restricted to dealing with just the 69 square miles of the District of Columbia. In fact, the majority of the GLBT community that law enforcement comes in contact with don’t actually reside in D.C. They might work here, they might socialize or be entertained but then they go home to their suburbs in Maryland or Virginia. If we say we’re not going to serve them then we’re leaving out a huge part of the GLBT community.

MW: How did you end up with this assignment?

PARSON: I didn’t volunteer for this position, I was directed to do this. [Chief of Police Charles H. Ramsey] said he needed me to do this and I’m a police officer and I do what I’m told. It’s actually a very funny story. I was on vacation in Colorado Springs. My vacation is normally doing something hockey related, so I was teaching a referee seminar in Colorado Springs at the Olympic Training Center. I got back to my room late at night and the oh-shit light was flashing on the phone — you know, you see the light flashing and you go, “Oh, shit.” I picked up my message and it said to call the chief. I did and he said, “Brett, how would you feel about taking over the Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit?”

I’ve been out since I came on the department so I knew that everybody knows I’m gay, it’s not a big deal. So I said that I was in charge of a major narcotics strike force and having a blast locking up drug dealers and solving homicides — I don’t think [GLLU’s] really what you want me to be doing.” He said, “No, I don’t think you understand. I’ve already transferred you. I just wondered how you feel about it?”

Capital Pride 2001 was my first day on this job. I came into it with anxiety and hesitancy. Up until then, if you mentioned my name to anybody who knows law enforcement in the Washington area, the first thing they would say was, “Man, he’s a good cop. By the way, did you know that he was gay?” My fear, and it will continue to be my fear for as long as I’m in this job, is that that will change over the years to “He’s the gay cop. He used to be a really good cop.” So I’m really fighting to make sure that this unit continues to do street level law enforcement and maintains the respect of our peers. That’s an important aspect of what we do because in order for us to effectively serve the GLBT community, we have to be respected by the law enforcement community.

MW: Is the problem that you may be perceived as being more focused on public relations than on actually arresting people?

PARSON: I cringe when I hear that. The two things that I hate to hear is that we are “administrative” and that we are “community relations.” We are police officers. We are on the street doing police work every day. Yes, part of our job also includes doing outreach to the community, training, education, singing “Kumbaya,” and doing all the community relations. And my job as a supervisor and commanding officer obviously has some administrative work. But crime is not getting solved by doing administrative work.

|

MW: How long have you been on the police force?

PARSON: Since 1994. My very first assignment was before I even graduated from the police academy. It was the year of the World Cup in 1994 and my academy class was put on the streets because they anticipated all this rioting and stuff surrounding the soccer games. Of course, none of that panned out at all. But I got to wear a World Cup police badge. My first patrol assignment after the academy was in the 4th Police District, which is up on George Avenue corridor. I worked what’s called the lower end, Columbia Heights and Mt. Pleasant. My dad grew up in the 4th District.

MW: What was the first time you came out after you joined the police?

PARSON: I have no idea because it was not a conscious effort on my part. When I chose to leave professional ice hockey to go into law enforcement, my partner and I decided it was going to be a non-issue. I was not going to change pronouns. I wasn’t going to be ambiguous about what our relationship was. And it was never an issue, from day one at the academy. So I really can’t pinpoint a day — it just didn’t happen.

Let’s face it, I’m not exactly a wallflower and if there was anybody who had a problem with it, chances are they probably weren’t going to stand up to me and say, “Oh, you’re going to fuckin’ hell.” It just wasn’t going to happen. Could somebody else who had a different personality have gotten away with it the way I did? Maybe yes, maybe no. I don’t know.

MW: You were born and raised in and around D.C. What was your family like growing up? How would you describe them?

PARSON: A circus. I come from a Jewish household, Russian Jews. Both sets of great grandparents came over from the old country. I didn’t grow up in a very traditionally religious house but it was definitely a Jewish house, you know, nagging and guilt and all that shit. And lots of chicken soup. My father owned his own company and was around an awful lot. He had control of his time. My mother was a professional dancer, and also kind of a stay-at-home mom. She spent quite a bit of time traveling the Washington Metropolitan area with dance groups, so I grew up running around the city with my mom and dad doing stuff. We had family vacations every summer. We’d pile into the Cadillac and be gone for a few weeks during the summer. It was a very positive, loving family.

MW: How was your coming out with them?

PARSON: I probably had one of the better experiences. I didn’t choose to come out to my parents until I had a life partner. And my [then-partner] and I had been together for about 6 months or so when both of us decided we wanted our families to know what was going on, so we both went to tell our parents on Thanksgiving. I had no anxiety about it. I knew my parents would not have a problem with it. It was just going to be a matter of delivering it.

My mom and dad were waiting for me because we were getting ready to go out for the traditional Thanksgiving Jewish meal of Chinese food, and I said, “Sit down, I want to tell you something.” I never do that. “What, what, what? We’re hungry,” my dad said. I said, “I’ve got something I want to talk about.” “Can we talk about it in the restaurant?” “No, I don’t want to talk about it in the restaurant.”

So we talked about my work in professional hockey at the time and how I was away from home and there are parts of me you never see. My father finally said, “What are you trying to say?” I said, “Well, there’s somebody in my life. And his name is Mike.” And my father said, “And we needed to stay away from the Chinese restaurant for that? Come on, let’s go.” No issue whatsoever. Didn’t miss a beat. We talked about it throughout dinner, and they called the neighbors over from another table: “Hey, our son’s gay, isn’t this great? Want an egg roll?”

MW: How did you end up working in professional hockey?

PARSON: I caught the hockey bug when the Capitols came to town back in the seventies when I was 7-years-old. I knew how to ice skate but when I saw the Capitols I knew that’s what I wanted to do. And the hockey was probably better suited for me as far as my personality. Looking back, it was a good way to get rid of some of that frustration and anxiety I didn’t even realize I had. [At least] through the physical part of it, because I’m not a very prolific scorer. I play a much more physical game.

I played youth hockey out in Columbia, Md., and established a reputation as not the most skilled player but one of the tougher players. I took my share of penalties. When I was 16, I was suspended and told I had to referee some little kids’ games. So I got up early on a Sunday morning to go ref hockey games for six-year-olds and I loved it. I skated for the whole game, they couldn’t kick me off the ice because I was in charge, and when I blew my whistle people listened. And they gave me ten dollars a game. It was great! I decided I wasn’t going to play anymore, I was going to be a referee.

When I was 17, I got a phone call from a referee who was working the Atlantic Coast Hockey League, which was like the armpit of the minor leagues. [The scheduled] referees couldn’t get in for a game in Roanoke, Va., because of snow. Of course I went. And it just snowballed from there. After a few years I got a call from the National Hockey League asking me to come into their training program as a referee. But I never intended for that to be my career at all. And that’s why I got out of it, because I wanted to be a police officer. That’s what I always wanted to be.

MW: When did you first know you wanted to be a cop?

PARSON: When I was born. [Laughs.] I’m one of those lucky people who was always sure of what he wanted to do. Like a little kid who sees a policeman on a horse and says, “I want to be a policeman.” I’ve never grown out of that. I still have that youthful stupidity towards this job — I can be surrounded by absolute horse shit and I’m thrilled because this is what I love doing. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

MW: You’re very well known in the community and you’re seen at a huge number of community events.

PARSON: I tell people all the time that there’s a fine line between famous and infamous.

MW: But you’re seen so much I have to ask, is there anything you want to do later in life? Do you want to run for political office?

PARSON: I am not a politician. I know there are lots of people who will read that and say, “Bullshit. Look at the way he works a room.” That’s my personality. That’s just me and the way I treat people. I’m not a consensus person. I don’t make decisions based upon what’s popular or based upon surveys or polls. Never have. If you look at the jobs I’ve had, I tend to make decisions that aren’t very popular. So my gut reaction to that question is always, “Fuck no.” But who knows what I’m going to be at 60 when my body finally poops out on me and I can’t chase drug dealers. Maybe at that point I’ll go back to school and get a law degree and become a judge. I don’t know. I’m here now and I don’t want to be behind a desk legislating. I’m an operations guy.

MW: Is it difficult to maintain your position as a police officer and still be getting out to these different kinds of things?

PARSON: I think the most difficult part of my job these days is walking that fine line between advocate and enforcer. That’s a tough line to walk. It’s tough to walk into a male adult-oriented business where everybody knows there’s illegal activity going on and to hug people and to say “hi” and to make them feel good that the police are around and we support you. But on the other hand, if I see somebody doing a hand-to-hand transaction I’m locking their asses up. And I have. I think the reason we’ve been as successful as we’ve been so far is that the community respects that duality.

I don’t know if it’s a good analogy, but I think GLLU’s role is a lot like a parent. We love you, we support you, we advocate for you, we will protect you to the nth degree, but don’t you fuck up because we’ll spank your bottom. You know, some people might like that. [Laughs.] That’s the duality of it, the tough love kind of thing. I happen to be really good at that. It’s my background in counseling also. I’m not one of those huggy, feely counseling people that you leave smiling. When you leave me after a counseling session, you leave emotionally drained. I think that’s living, getting the core emotion. Whether you cry or you laugh, it’s still a good thing.

MW: Given your work in narcotics, is drug trafficking something you see playing a big part in the gay community? People tend to think of dealers and networks as other people in other parts of the city.

PARSON: Yeah, they think of a young black kid on the corner, slingin’ crack. That’s not my reality these days. I don’t think the GLBT community has really come to a realistic conclusion of how bad the drug problem really is. Now, you have to understand, I include alcohol as a drug. So when you add alcohol to all the illicit drugs — crystal meth, Ecstasy, GHB, ketamine — we’re talking about over 90 percent of the crimes I deal with involve drugs in some way. Either the victim was drunk or high, the suspect was drunk or high, a witness was drunk or high or everybody was fuckin’ drunk or high. That’s scary. And the community has yet to sit up and take notice just what an impact drugs are having. Just the fact that I lump alcohol in there freaks people out. But when I’ve got people who can’t stand up and they’re getting robbed, we got a problem. We’re drinking ourselves into oblivion. When you’re getting robbed and called “faggots” and I show you a picture of the suspect that I know did it and you go, “I can’t remember my fuckin’ name,” how do you expect me to solve that?

I want to make sure I’m clear: I am in no way saying that victims are responsible for the crimes they’re victimized by. What I’m saying is that if you’re going to ask me as a police officer to advise you as a community how to keep safe, I think the number one way to do that is to prevent yourself from being victimized. And the only way to do that is for you to have all of your senses working for you — being aware of your surroundings, making good judgments. It sounds like common sense but it’s common sense that usually falls to the wayside when a lot of these things are happening. I’m not blaming them for it. Anybody should be allowed to stumble or crawl home from a bar in D.C. or anywhere in this world, and have an expectation that they’re going to make it home safely. But there will always be people who take advantage of vulnerable people. And to the extent that we can make ourselves less vulnerable, we should do that.

MW: There is a stereotypical view that gay neighborhoods are safer.

PARSON: Oh, bullshit. You remember Adrien Alstad being killed [on his way home from working late at Annie’s last summer]? After we caught these people, everyone was jubilant and said, “I feel so much safer now that they caught these guys.” And I was saying something that I think people were being taken a little aback by, which was, “Don’t feel safe.” Let’s take something positive out of Adrien’s death, which is that we need to be vigilant. Crime occurs everywhere and regardless of whether you’re on 17th Street in Dupont Circle or Barney Circle in Southeast, you need to be vigilant. You need to be aware of your surroundings. You need to tell people where you’re going and you need to be sober while you’re doing it.

I am always fearful when a crisis occurs, that there’s this initial reaction where the community rallies and there are calls for public safety and cries of “we need to take care of each other.” Then the crisis ends and we all go back to our little naïve world. I don’t want people to remain in their little naïve world. I don’t think that vigilance is a bad thing. Paranoia is a bad thing, but there’s a difference between paranoia and vigilance. I think people need to remain vigilant no matter where they are.

I’m probably one of the only people in the gay community that walks anywhere in this city and I’m not going to get goose bumps. I carry a fucking gun and I know how to use it. Everybody else? Be fearful. Goose bumps are a good thing. An adrenaline rush is a good thing. Your asshole puckering up to the size of a pinhole is a good thing. That’s God’s gift to you of human instinct.

The Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit office is located at 1369-A Connecticut Avenue NW (entrance on Massachusetts Avenue side). Call 877-495-5995 for paging, or 202-727-5427 to leave a voicemail. For more information about GLLU visit www.gaydc.net/gllu.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!