Note for Note

The National Symphony Orchestra's Emil de Cou brings music to the masses

A word of advice to those planning to attend a concert conducted by Emil de Cou: Remain in your seats. No autopilot standing ovations, please.

Unless — unless — you are moved by the passion of the music, unless you feel as though de Cou and the orchestra have really, truly earned it. In that case, exclaims the Associate Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra, go ahead and “act like you had a great time!”

“I like when people respond honestly,” he says, “because many times people who come to concerts regularly, they are not as engaged as people who are having the visceral excitement of hearing it for the first time.”

|

The fortysomething de Cou is one of America’s foremost conductors. (Oh, and he happens to be gay, partnered for 21 years with another out gay maestro, Leif Bjaland, Music Director of Connecticut’s Waterbury Symphony Orchestra.) Before landing at the NSO in 2002, de Cou worked primarily with the San Francisco Ballet and for the American Ballet Theatre.

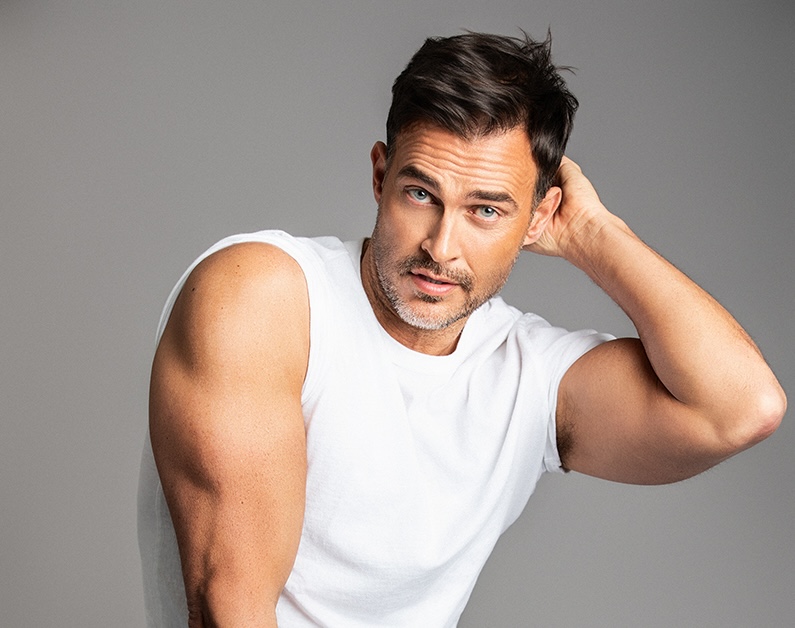

Tall, classically handsome, and refreshingly candid, de Cou was recently named the inaugural NSO@WolfTrap festival conductor. And next Friday, July 29, at Wolf Trap he’ll lead the orchestra in perhaps its most unique performance ever: they will provide live, note for note orchestral accompaniment to the beloved classic, The Wizard of Oz.

“The [producers] were going to premiere it at the Hollywood Bowl,” says de Cou during a recent late morning chat in the Eisenhower Theater’s bird room, “but it was cancelled. So ours is going to be the premiere.” While he admits that playing in time to the 1939 movie musical will be “tricky,” he’s looking forward to the challenge — and to the opportunity to present Oz‘s lavish score in a way that no one’s ever heard it before.

Growing up in what he calls “a pretty homophobic atmosphere” in Orange County, Calif., de Cou took refuge in his high school band room, where his teacher frequently let him conduct rehearsals. Unlike other high profile conductors, de Cou is not into showboating (“I like to promote the music and the orchestra”) and he feels most strongly about the part of his mission allowing him to helm the NSO’s semi-annual American Residencies, in which the orchestra tours through individual American states, free Family Concerts, and the esteemed and essential Young People’s Concert series.

“Each year, we have about 30,000 D.C.-area kids come through and hear the orchestra play a really terrific program,” he says. “I think that’s the most important thing I do. Because for many — if not most — of these kids, it’s the only time they hear an orchestra or live music.”

Refreshingly down-to-earth and gently-spoken, de Cou is frustrated by what he calls the “perceived snobbery” of classical music and the fine arts.

“It drives me crazy,” he says. “It’s perpetuated by the media. You see it in films and commercials and I think it’s really harmful. It’s a way of preventing people who are not of means — people who need the arts as a way of having a complete life — from coming to the arts. It’s a bad thing.

“The arts can be the great equalizer,” he continues. “Everybody [should be able] to experience classical music. We have cheap concerts, we have free concerts, they’re accessible. And we should be doing more. The American promise doesn’t work unless everybody has equal access to all great things that exist.”

METRO WEEKLY: When did you first develop an interest in classical music?

EMIL DE COU: I came from a family that didn’t have classical music because it wasn’t part of my parents’ world. There was a lot of jazz, because my dad’s from New Orleans, but my parents came from a working-class background and they didn’t have the means or the exposure to classical music. I knew that I wanted to play an instrument, not exactly knowing what or how. My uncle played an accordion, so suddenly I was given accordion lessons. [Laughs.] What a horrible thing that was. It just didn’t resonate with me….

I attended a high school where they had a really good in-school music program. I went to the band director and said ”What can I play?” He gave me a French horn and a few months later I was in a marching band uniform. It was really terrific. You know, being a teenager is awkward anyway, but being a gay teenager…[the band room] was like a safe place in my high school. I’d just hang around with all my nerdy music friends. My teacher knew I loved music, and she took me and a friend to see Fantasia. From that point on I knew conducting was what I wanted to do. It was the ”light going on in your head moment.” I just thought, “I can do that, I want to do that, I will do that.”

|

MW: Did you study with anyone of note?

DE COU: I studied with a lot of different teachers. But my last teacher was Leonard Bernstein at the Hollywood Bowl. The physical act of conducting is unique to your body. I’m 6’3″, and Bernstein was extremely short, and so what he could do physically, if I tried to mimic him, I would look ridiculous. So in that regard you can’t have somebody say ”You must move your arm exactly like this.”

Conducting is an emotional gesture you’re giving to the musicians, especially a great orchestra like the National Symphony. They really don’t need a tick-tock metronome beat. They could stay together pretty well with practically anybody [conducting]. What they want from a conductor — what they respond to — is someone who is incredibly passionate, to the point of raw emotion, at rehearsals and, especially, concerts.

MW: How much of an orchestra’s performance a result of who the conductor is?

DE COU: The conductor does most of the work in rehearsals — that’s the thing the audience never sees. In a sense, the performance is an elevated version of the rehearsal. But a conductor is sort of like a film director — I see the conductor as being ”off camera.” I’m not a fan of the idea that people go to a concert to watch the conductor. I’d rather they watch the musicians or just close their eyes.

MW: Still, sometimes audiences attend specifically to watch the conductor. Bernstein, for instance, was famous for his histrionics.

DE COU: Bernstein was like a cult personality — his live performances became more exciting as an event than if you were to listen to the recordings in a dispassionate way. He was so charismatic — he would fill a room with his personality.

MW: He was also famously closeted.

DE COU: Yes, he didn’t come out until shortly before he died. He was also self-loathing as a Jew, and certainly to a degree as a gay man. Anti-Semitism and homophobia prevented him from becoming a music director in Boston and a lot of other places. He actually had disdain for people who were openly gay. People who were bisexual or closeted he went a little easier on. But when he left his wife, and his partner died of AIDS, it sort of turned him around. He was a very conflicted person.

MW: What kind of reaction do you get when people learn that you’re gay?

DE COU: Here [at the NSO] it doesn’t matter. And it doesn’t matter so much in large cities because large cities by nature are cosmopolitan. I hate to say it — no, I don’t hate to say it — but where the arts thrive, people tend to be more liberal because they think and they’re open-minded. And generally in liberal, open-minded communities you don’t have prejudice. In smaller cities, where people are narrow-minded, they might have the arts but they want it in their own way — which excludes people they don’t want or people they don’t like. In modern day culture people don’t come out and say they don’t want you because you’re a Jew or black or gay, but they’ll find some code for it, some wink-and-nod way of saying that you’re not the right fit.

MW: Can you perceive your sexuality ever keeping you from being named a music director?

DE COU: In certain places, yes, I think without question. I’ve heard of it happening. I won’t mention his name, but a friend of mine is a very talented conductor. And he’s been out and with his partner for many years. He doesn’t come in the room like some ’60s communist freak or something. He applied for a position of music director. And the final question some guy on the orchestra’s board asks is “Is there anything in your personal life that would bring shame upon the organization?” And my friend thought, ”Well, what possibly could he mean?” They wanted to know if he’d stay closeted or if he’d do an Act-Up protest or something as soon as they made him music director.

The orchestra doesn’t care if the conductor is gay. They want some honest music-making. They want to be inspired. The boards seem to care more because the conductor is looked at as their equal — you’re at the top of the pyramid. And boards are generally run by the heads of business.

MW: Which is what you pretty much have at the Kennedy Center.

DE COU: Yes, but we are very fortunate to have a smart, open-minded board.

MW: More and more, the arts are being de-funded, and financially strapped high schools are shuttering their music programs.

DE COU: I get angry when they take music away from schools because something resonates in human nature with the arts and music that no other thing can give to you. And in school, especially in teenage years, it’s like the special ingredient that you need to become a human being. It can change your life, or put you on a new track, or make you a better-rounded person. Without the arts or music, you can be adrift for years. Because if you don’t get it at that age, it can mess you up. Not all kids, but for kids who don’t fit into certain cliques, the outsider kids, who wind up maybe morphing into something violent or ugly. Because great music is a great emotional outlet. You can throw yourself into a whole Tchaikovsky symphony and wallow around for a while and have some emotional fulfillment….

|

A civilization’s culture used to be judged on artistic and imaginative creativity, not on huge SUVs and pointless wars and aggression and violence. We live in a shallow time with shallow leaders. The arts is the great corrector. Without the arts, the country will spin off into some empty shell of what it was supposed to be.

MW: It’s what we leave behind that we carry into tomorrow, be it legacies of technology, legacies of war and destruction. But I agree with you: some of the most potent legacies are those that are artistic in nature. Music transcends boundaries. Anyone can listen to Tchaikovsky, for instance, and have a response.

DE COU: It’s so powerful. That’s why these concerts we do at Wolf Trap and at Carter Barron in the summer are incredibly important. They’re not all profound Mahler symphonies; we do some silly, light pieces as well. But I always try to put something in that has substance so people can be moved. And it’s so needed now because we live in such horrible times. Music is the invisible voice of mankind.

MW: Do you feel as though classical music is in any kind of danger of losing its audience?

DE COU: I don’t think so. Our country now has more orchestras than it ever has had — we have, per capita, more orchestras than Europe, and that’s where classical music came from. But the orchestra world moves very slowly. If you look at a symphony concert, it pretty much is presented in the same manner as it was presented a hundred years ago. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but trying to move forward and make it more modern without breaking it is the trick. And you have to do that, as they say, very delicately because it’s a very fragile thing you’re dealing with — a huge, invisible, intangible thing. You can’t let the art form just sit like a museum, because it will atrophy and die. But you can’t slick it up and make it something it’s not because then you’ll have ruined its magic.

MW: So what’s the answer?

DE COU: If I knew that, I’d make a million dollars and off I’d go. [Laughs.] It’s being done slowly and people are experimenting. At most symphony concerts you have an overture or short piece, a concerto, an intermission and a big symphony. And that’s pretty much the format. If you looked at first concert Tchaikovsky did at Carnegie Hall, it was like a weird grab bag of all sorts of short pieces. It was much more eclectic, almost like symphonic channel surfing instead of this holy trinity of three pieces on a program.

Concerts, especially in the 19th century, were just more exuberantly thrust together. But there is a rhyme or reason to how they were done. I think you can still have a great symphony on a program, but I also think if you just make it a bit more surprising, it engages the audience more because they’re not quite sure what’s going to happen next.

MW: Are you doing your part to bring that element of surprise to concerts?

DE COU: Well, I try to with the things we do in the summer. But to really do it, I would have to have a very indulgent board of directors and a lot of money and my own orchestra.

MW: Let me ask you about The Wizard of Oz. How does the live orchestra incorporate itself into the existing soundtrack?

DE COU: We take the music track off the film and the orchestra plays along in its place using the original scores. The problem with The Wizard of Oz is that MGM threw away their entire music warehouse to make room for props in the ’70s. So this very elaborately written score by Harold Arlen and Herbert Stothart was thrown in the garbage. So they recreated the whole orchestra soundtrack the way it was recorded in Hollywood in 1938 and we will play it live in sync with the film. It’s very tricky to pull off. We’ll accompany all the songs, all the dances, all the underscoring. It’s like somebody cleaning the Sistine Chapel. You’ve known this film so well and you are somewhat aware of the underscoring but to hear it played live….

I was listening to the score and watching the film again and they do clever things that I wasn’t even aware of even though I’d memorized the film. The sound of the orchestra changes from when you’re in Kansas to when [Dorothy] opens the door to Oz. Suddenly, all these instruments are used that had not been heard in the first 15 minutes of the film. It’s very subtle but very powerful.

MW: Do you have a favorite classical piece?

DE COU: Almost anything by Tchaikovsky. Certainly Tchaikovsky’s “Fifth Symphony,” if I had to name one piece. There are certain composers that you feel like you know exactly why they wrote what they wrote. It’s almost like getting in their skin, and that particular piece brings me to tears.

MW: What’s one piece you never want to conduct again?

DE COU: There are so many, really. It used to be [Ravel’s] ”Bolero” but actually I’ve gotten kind of fond of ”Bolero.” Still, it’s what a friend of mine calls musical crack. It’s cheap, it’s bad for you, but people love it.

Emil de Cou and the NSO will accompany the MGM classic The Wizard of Oz, on Friday, July 29, at 8:30 p.m., at Wolf Trap, 1551 Trap Road, Vienna, Va. On Saturday, July 30, the NSO will present music from movie classics, including 2001: A Space Odyssey, Singin’ in the Rain and An American in Paris. In-house tickets are $28-$38. Lawn is $18. Call 703-255-1860, or visit www.wolftrap.org. For more information on the NSO’s season, visit www.kennedy-center.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!