Royally Wronged

The Washington Shakespeare Company has concocted a 'Royal Hunt' that resides between the sublime and the subpar

For many ancient cultures and aboriginal tribes, worshipping the sun as a sovereign deity was as natural to life as eating grain and breathing in fresh air. For the Incans, they worshipped their earthbound god as no less than the son of the sun, a belief that inspired cruel intolerance and mockery from a relatively small army of Christian Spaniards in the middle of the 16th Century. And although the soldiers were outwardly determined to convert the peaceful natives to their own spiritual inclinations, time would reveal their authentic idol as nothing more than shimmering, shiny gold.

Peter Shaffer’s historical retelling The Royal Hunt of the Sun visits that tempestuous South American conquest with an eye for justice and a nose for sniffing out hypocrisy and religious tedium. It’s a sprawling, intimidating script from the author of Amadeus and Equus, dressed with lofty ideas and competing themes of politics and theology. There are unresolved questions of loyalty, honor, and faith, and although director Steven Scott Mazzola doesn’t attempt to update Shaffer’s 1965 epic drama, it’s the kind of resonating theatrical literature that highlights the notion that entire nations and unscrupulous rulers still commit unfathomable crimes in the name of their gods, hiding under a veil of religious sanctimony and diplomatic integrity.

Captive audience: Mezzacappa and Pereya (Photo by Ray Gniewek) |

There are peaks and valleys of drama in Washington Shakespeare Company’s rugged production, which is nothing if not visually articulate and musically astute. WSC employs original work from Mariano Vales, whose lush melodic interludes and drifting incidentals provide a sublime, enchanting score that consistently moves the story forward. Vales’ captivating combination of Shaffer’s text with poetry and indigenous Quechuan music is delivered by a serene trio of women (Leslie Sarah Cohen, Katherine E. Hill, and Beth Madeline Rubens), and Krissie Marty is credited with imaginative choreography indicative of traditional Incan gestures.

The sparse set designed by Matthew Soule features an enormous cloth backdrop bathed in the shadows of Ayun Fedorcha’s ambient lighting, and Cynthia Abel Thom’s costumes merely hint at the period without bearing elaborate, heavy armor or expensive artillery. The effect is tasteful and feels appropriate for the dark, hollow playing fields inside the wide Clark Street space.

It seems that Mazzola, who by day works at The Shakespeare Theatre, has learned a thing or two from that theater’s Michael Kahn on moving actors around a stage. While he demonstrates a gift for lively, physical staging and graceful pageantry, his troupe toggles back and forth between presentational college fare and a mature brand of unique stagework. The ensemble is energized by rousing group scenes, but the smaller duets and trios frequently fall flat. Mazzola also employs a curiously inconsistent form of sign language that lends no value to the exchange, and the use of the same actors in multiple roles adds a confusing dimension.

|

For all of their dense ruminations on soul-searching and self-preservation, the general execution by the actors lacks the same spirit that drives the dialogue. They make lovely music together, but not much else by way of heartfelt conviction on matters of death and glory. As the arrogant commander of the expedition, James Foster Jr. offers a wooden, recitative performance, and Daniel Ladmirault’s self-righteous chaplain is rife with scornful melodrama.

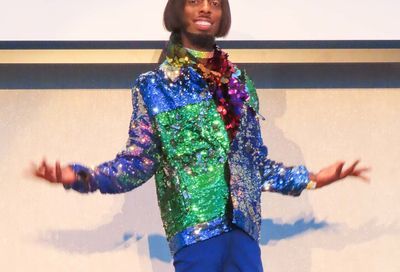

Thankfully there are exceptions, and ironically enough, it is Peter Pereyra’s Incan god Atahuallpa who brings the most humanity to Shaffer’s story. The second act opens with Atahuallpa held captive by the conquistadors, and Pereyra is in fine form as a humbled Peruvian lord who must win over his enemies. As he dances and fences with the opposition, Pereyra is a convincing force.

The saga is regaled through an apprentice narrator, and like a young Luke Skywalker, Matt Mezzacappa is an engaging presence as the ”little lord of hope” pageboy to Foster’s general. The older version is portrayed by Jim Jorgenson, and the effect is a ghost’s memory of how a fraternal contract borne out of greed sparked the fall of the Incan Empire.

Ultimately Shaffer’s play is produced for its lingering effect and inevitable post-show debate, not for its convoluted drama and inelegant plot. And while their ambitions are admirable, WSC has concocted a Royal Hunt that rests somewhere between the sublime and the subpar.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!