Red, White and Bleu

Bleu Copas joined the Army in the aftermath of 9/11 -- but the Army decided it didn't want his help

Bleu Copas was 20 the first time he visited New York City — a trip that included a visit to the observation deck atop the South Tower of the World Trade Center. He remembers pressing against the glass for a better view. Five years later, back home in Tennessee, he saw it all come crashing down in the horror of 9/11. He says he recognized that moment as a historic turning point not only for the world, but for himself.

”I grew up with a lot of men around me who had been in the military. It was always something I looked up to,” says Copas, who had taken ROTC courses in college. ”When 9/11 happened, I was in graduate school for counseling, but I felt my services were needed.”

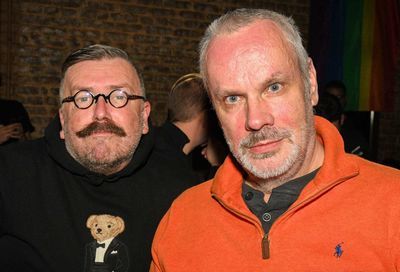

Copas |

The line from Sept. 11, 2001, to March 24, 2007, the night of the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network’s (SLDN) annual national dinner in Washington, is one that Copas could not have seen coming. It’s a line dotted with commitment, patriotism, investigations, insult and achievement, culminating with Copas’s scheduled speech at the SLDN dinner. And it’s another example of the minefield that gay soldiers navigate in the United States military.

Copas’s story starts with him as a young man raised in the Deep South, in a socially conservative, Christian family. For the most part, he played by the rules and didn’t make waves.

”I wasn’t out to anyone except my boyfriend,” Copas says of the years just before 9/11. ”We were in a relationship for four years. Oddly enough, he was the son of my battalion commander when I was taking ROTC classes. I eventually came out to my sister and my closer friends. There were mixed reactions, but all supportive. Though some of my friends were ‘supporting’ me through their prayers, to help me out of homosexuality.”

With his low-key relationship, academic achievements and ROTC, possibly the only rule Copas was breaking at the time was donating blood. As gay men are asked not to donate, he lied to give blood.

It’s the same sort of lie Copas had to tell when he enlisted in the Army in May 2002. Since Congress enacted the so-called ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue, Don’t Harass” policy into law in 1993, the military maintains that homosexuals are a threat to ”high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion,” but that those who can keep their homosexuality a secret won’t be rooted out.

”I knew about ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ going in. I was pretty much on my own, but I do a good job of feeling out a situation, knowing when it’s safe. … I was led to believe there wouldn’t be any ‘witch hunts’ as long as I held up my end of the bargain.”

And Copas did hold up his end of the bargain, making himself an exemplary soldier and officer, completing his basic training in October 2002 at Fort Jackson, S.C., before heading off to the Defense Language Institute (DLI) in Monterey, Calif., to become a Arabic linguist.

”In basic training, I was the ‘soldier of the cycle.’ I was a great leader,” says Copas, pointing to the distinction given to a single soldier during training. ”I was not the best linguist, but I was one of the top linguists.”

Throughout, says Copas, being gay did not interfere with his military duties. From Monterey to his final post at Fort Bragg, N.C., he says he enjoyed his time in the military and performed well.

”That community [in Monterey] was completely accepting and affirming,” he says, adding that the military-intelligence community at DLI was home to other gay soliders. ”I always felt at home. I had a close-knit group of friends who became my family. But even when I got to Fort Bragg, I didn’t feel threatened. I didn’t feel like there was homophobia in the air.”

His time in the Army even gave him the confidence to come out to his parents. Their reaction was not, however, on par with the reception he was finding in some open-minded corners of the military.

”I didn’t come out to my parents till I’d been in the Army about two years. It was horrible. It wasn’t rejection. It was like they were just completely disappointed. … Although they still love me, you could tell their trust in my word went down a few notches.”

The reaction from Copas’s parents may have been a sign on things to come: anonymous e-mails to Copas’s superiors, outing him as gay. At Fort Bragg, doing a lot of ”counting and cleaning,” as he waited to deploy — presumably to the Middle East where he could apply his training intercepting and translating Arabic radio transmissions — Copas joined the 82nd Airborne Division All-American Chorus. The e-mails outing Copas were directed to the leaders of the chorus, prompting them to ask Copas if he was gay.

”We’d go through these trainings each month about equal opportunity in the military. ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ was always addressed. And then it was just blatantly ignored. … I was asked flatly by my leaders in the chorus [if I was gay],” Copas recalls. ”I worked with SLDN once this all started. The moment that I knew something was going on, I called them. We were under the impression that if the policy had been adhered to, my case would’ve been dismissed.”

Copas says he and SLDN believed there were three points that should’ve led the Army to dismiss the case: First, the accusations were, and remain, anonymous. Second, Copas’s superiors, apparently ignoring policy, asked Copas is he was gay. Third, there was no evidence of homosexual conduct.

Those points, however, did not protect Copas. He was honorably discharged in December 2005 with the rank of sergeant. His dismissal was, however, notably newsworthy, illustrating for audiences across America how the ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy effects all Americans when anti-terrorism assets, such as Arabic linguists, are fired. Copas was asked to tell his story widely, to the New York Times and the Associated Press, for starters, and to audiences of Good Morning America and even The Daily Show With Jon Stewart.

”It was a bit of a shock initially,” Copas admits. ”I didn’t expect this big a reaction. It’s strained my familial relationships quite a bit, but I’ve also found so much support.”

He’s also found that despite being kicked out of the Army for being gay, the experience has not tainted his patriotism, as evidenced by his singing the National Anthem as the 2006 SLDN dinner.

”It was very emotional. My emotions were still high. At that point, it was like an affirmation of my contributions, of me doing my duty. SLDN was recognizing the fact that I had served.”

His parents have acknowledged his service as well, trying to overcome their discomfort with their son’s sexual orientation. Copas’s mother, for example, decorated his room at home — where he lives while completing his graduate studies at East Tennessee State University — with a floral arrangement marking Veterans Day. His father, Copas says, has offered his admiration for his son’s service and fight against ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Recent comments by Gen. Peter Pace, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, arguing that homosexuality is ”immoral,” indicate the military may be slower to change.

”I see my role as a voice for so many who have to remain silent. [And] in a position like this, you sometimes have to curb your views. I think Gen. Pace lost sight of that idea. His main job is to represent everyone in the military. In my opinion, what he said was just totally disrespectful.”

Copas says he’ll be talking about Pace’s comments in his SLDN speech Saturday — a speech he’ll begin in Arabic, even as he laments that his Arabic language skills are getting rusty. He does not, however, lament his time spent in the Army.

”Looking back, I’d still do the same thing. I might be more cautious. … If the policy wasn’t in place, I’d still be serving my country — and doing a damn good job.”

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!