Trans Awakening

Earline Budd's journey has been difficult and dangerous -- and led her to bring compassion to her activism

On Wednesdays, Earline Budd is behind bars.

It’s usually from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. when the 51-year-old spends her time at the D.C. Department of Corrections. She’s there by choice, serving not time but her clients –talking to gay and transgender inmates about their plans upon being released.

It’s a discharge-planning volunteer effort Budd started more than six years ago and it’s become one of her many duties as a treatment and healing specialist for Transgender Health Empowerment (THE), an organization that she helped found in 1996.

As a local activist, Budd also lends her time to other efforts, notably her recent testimony before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee in support of including transgender people in the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA).

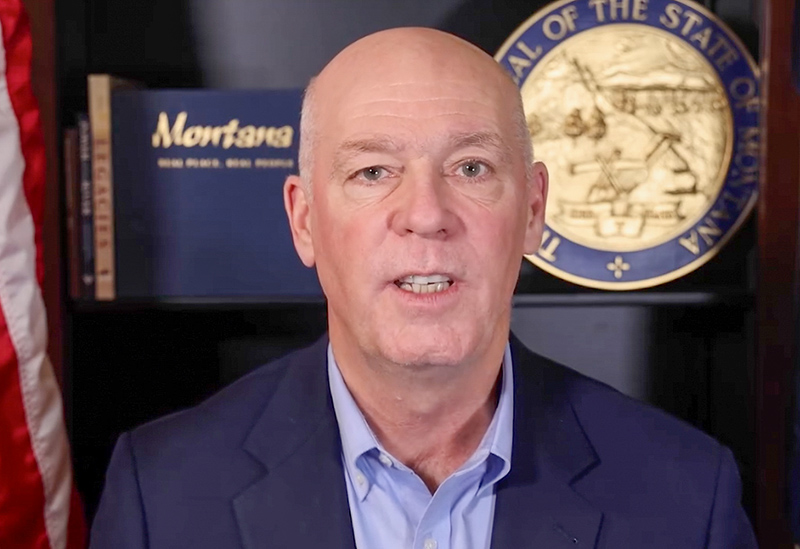

Earline Budd

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Budd herself will be the first to admit that she has not led a completely immaculate life. Her passion to help others stems from her own struggles as a transgender woman, from incarceration as a teenager to living on the city’s streets as a prostitute and drug user.

Budd managed to find her way out of the darkness to emerge as one of LGBT D.C.’s most prominent figures.

”She’s the Oprah Winfrey of the transgender community,” says a client at THE’s offices.

”If it wasn’t for Ms. Budd, I would be dead. No doubt about it,” remarks another.

Friday, Nov. 20, marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance, which THE, the DC Trans Coalition and others will observe with a nondenominational evening service at the Metropolitan Community Church. Budd will spend that day thinking about the senseless violence and indifference that has claimed the lives of so many in the city’s transgender community.

Tyli’a “NaNa Boo” Mack, who was stabbed near the THE office in August of this year. Elexuis Woodland. Stephanie Thomas. Ukea Davis. Tyra Hunter.

The list, as Budd says, is endless.

The list is also a reminder of the difficult path Budd has taken, in her own life and in her choice to serve others.

METRO WEEKLY: The people you are helping here today, what are they doing at Transgender Health Empowerment?

EARLINE BUDD: Because I’ve been volunteering at the jail now for over six years, they have given me the ability to have what we call a support group, as well as conduct individual sessions in what’s called discharge planning. I actually work from the jail to help get transgender inmates set up and connected to services so that once they get released from jail, they come to THE. Many times some of them don’t come here. They find themselves back on 5th and K [an area known for prostitution]. What I have to do then is become creative and do outreach and just try to do harm reduction and get them back in.

MW: What do you do when you meet with inmates in D.C. Jail?

BUDD: If they’re transgender, I ask are they being treated fairly while they’re in jail? Are they getting their hormone therapies? Are they getting mental-health services? Are they getting substance-abuse programming? I collaborate with Unity Health Care and the Department of Mental Health in the jail, so once we get that situated, then we start talking about the target release date. Many of them are serving no more than 90 to 120 days, so at that point I say, ”Once you get to 60 days, then we need to be talking about what services we’re going to be providing you when you come to the community.”

MW: What led you to start this program?

BUDD: I decided to do it because of my history. I knew, being an ex-offender myself, what services were not being provided in terms of while you’re in jail and when you’re coming home. In 1994, I was released out of federal prison and that’s when I started going to the group called TADD, Transgenders Against Discrimination and Defamation. That group is where I started doing my outreach — then the Department of Health approached me and asked if we wanted to become a nonprofit.

In 1996, we were awarded $20,000 dollars to do capacity building to become a nonprofit organization. Up until ’96, we were a support group of just four or five individuals. Dee Curry was the director of the group and then I took over. Within three years I built the group up to about a 100 members. In terms of what name we should use, we said that most of the people who will be attending are transgender. We talked about despairing health issues that we have around denial, HIV and substance abuse. And then we talked about self-esteem, which is driven by empowerment. And that’s how we got Transgender Health Empowerment, T-H-E.

MW: Do you ever get tired of the work you do?

BUDD: I have gotten tired so many times. I think what keeps me going is that every time I look at someone that walks through the doors, that has a sense of hopelessness, and they’re struggling, I start to think back to how it was for me. And immediately it just hits me: I can’t let them go back out that door with a sense of hopelessness. I want them to leave knowing that there is help. I’m 51 years old, I’m HIV-positive, and when I came up in the latter part of the ’70s and then the ’80s, these services were inconceivable. They were nonexistent. I’m just so happy to be a part of something where we can see that there is success.

MW: Let’s go back to your childhood. What is your earliest memory of being transgender?

BUDD: At the age of 9 my family was struggling with what they were calling my ”gender identity.” My mom later told me that she would be laying out clothes for my sisters and myself, and what she said to me was, ”We would lay out your pants and shirts for you to get into, and we’d come back up and you’d have on your sister’s clothes every time. So when you became 10, we decided to take you to have your head checked-out because we thought there was something clearly wrong with you.”

They took me to the old Children’s Hospital on 11th Street, and had me go through the mental health [department] and I played with blocks and did all of that, came out, no problems, no mental-health issues. Then my physician — I’ll never forget his name because it was Dr. Gay — he did a lot of physical stuff, in terms of checking my chromosomes, my genes. I was actually at the age where they talked to me about what was going on because my parents were semi-illiterate. They had kids at an early age and never got an education. But the fact was that they came back with [a chromosome-based diagnosis] and it was causing me to act out feminine tendencies.

MW: What happened when you started to hit puberty?

BUDD: Well, I was fully transgender at 14. I didn’t identify with male clothing, so as I started getting older, I would find something of my mom’s or sister’s to wear. By the time I was 13, I was actually looking at other guys in the bathroom in school, and wanting to be in the cheerleading squad, just all those things that little girls do. My idol back then was a Flip Wilson character called Geraldine. When I was 13, hitting the streets, I would tell my mother that I had to go to school for a school play in which I was playing Geraldine. But I was actually dressing up in girl’s clothes and going out.

MW: How did you make that leap to the street?

BUDD: It just happened. When I was 13 my mother had picked up on the fact that I was wearing her bras and panties. She had a problem with that and she locked them up. I decided that if my mother wasn’t going to give me these things, I was going to go steal them. When the police caught me, they called my family and told them, ”We have your son here, he’s dressed in girl’s clothing and he was trying to steal some panties and bras.” And my parents said, ”We don’t want him back, not as long as he’s acting like that, maybe you could take him and straighten him up.” The police said they couldn’t take me in unless my parents said I was out of control. And my parents said I was out of control.

They put me in a program called PINS, Persons In Need of Supervision, at the age of 13. I stayed in there, locked up, for four years. They kept calling my parents, telling them I was there, and my parents would say they couldn’t take me back if I’m still acting like a girl. When I was 17, they couldn’t hold me any longer.

It absolutely did make me feel abandoned. I remember so clearly how I wrote letters saying things like, ”Daddy, this is your son, a child who’s gone astray, I realize that I’ve done wrong, but now I’m straight and I’m okay.” I was lying. I did that because I wanted to go home. But I didn’t get home. Not that way.

MW: When you were released, did you go home?

BUDD: Yes. When I came out I went home and I knocked on the door and my sister came downstairs, I’ll never forget it, and she said, ”Mom, Dad, Shorty is at the door.” That was my nickname. And then I heard someone say, ”How does he look? Has he changed?” And my sister said, ”You’re not still faggy are you?” And I said something horrible and slapped my sister. She hollered and told my father and he came running down the stairs with a hammer. He chased me to 14th and U and assaulted me by hitting me in the head with the hammer. I pleaded to him to stop, and people around us were saying, ”Don’t hit him again,” so he didn’t. He left me there, lying on the ground. At that point I knew it was all about survival. That was the first night of my life that I was homeless.

MW: Where did you go?

BUDD: I had heard about downtown on 9th Street where the transgenders were. But they weren’t called ”transgender,” they were called ”drag queens” back then. So I went down there and met some older transgender women and they took me under their wings. I told them I was put out by my family and had no place to go and they told me, ”Girl, you have to grow up fast. There’s going to be things you have to do in terms of surviving.” I asked them what, and they would take me to the bars and say, ”You see all these old men sitting around smoking big cigars? They have money. And they’ll give you money, but you’re going to have to do things you may not want to.”

Because I had been incarcerated during my juvenile period, I was well aware of sex. It wasn’t like I was a virgin. I had had boyfriends and everything when I was incarcerated. So one thing led to another, they showed me how to prostitute. I worked for a couple of different pimps in those years — made some quick money, ended up getting my first room in a run-down shack, paying like $30 to $40 a week for it.

MW: Were you afraid for your life at that point?

BUDD: I was afraid of having someone else running my life. I would make the money and it would go to them? They would buy me coats, clothes and cosmetics and feed me, but it was frightening, being 17. One of the pimps I worked for didn’t know at first that I was transgender and he had taken me out for four or five dates. He took me to dinner at a place called the Ebony Inn over on Sheriff Road and showed me off to the other pimps and they said, ”Oh, she is so fine.”

When you have a pimp, eventually they ”break you in,” so when we got ready to go to bed, he went to break me in and found out it wasn’t to be broken in, that in fact I had [male genetalia] and he went off. He went and got a gun out from the drawer and pointed it at me and I saw my life flashing in front of me. He said, ”You’re not a girl, you’re a faggot, you’re a man. How dare you?” And then he told me that he had spent too much on me to kill me, and that I was going to make all the money that he spent on me back, or else he was going to shoot me dead. So he was taking me back to 14th and P to prostitute, and make his money back.

So he was sitting across the street in a car with the gun. He had me on the corner prostituting, and he said that when I got in a date’s car he would follow and make sure I turned the trick, then I was supposed to turn the money over to him. The car that I got into turned out to be an undercover officer. He said to me, ”Don’t act strange, stay calm. We know that in fact the gentleman across the street is a pimp. Does he have you out here against your will?” And I said, ”Yes.” He said, ”Is he armed?” And I said, ”Yes.” He said, ”We’re going to pull out so he can follow us, and then squad is going to jump out and capture him.” And that saved my life.

MW: Did you get arrested as well?

BUDD: No, they let me go. And I ended up going back downtown and prostituting. I had learned the ropes. The older girls had told me how to make money. I would stay in the hotels. Sometimes I would sleep in alleys or in abandoned cars. Prostitution led to me getting further involved in criminal activities. I found myself going back through the jails and the criminal justice system, going back and forth.

MW: What changed? How did you begin to find your way out?

BUDD: Finally, this was in the late ’70s, I had heard about a gay group that was meeting at Church Street called the Gay Activists Alliance, and I thought that if I got myself connected, maybe I could get help. I went there and the organizers saw me sitting in the back of the group and said, ”Come here, little girl.” I told them I wasn’t a girl, that I was just wearing girl’s clothes, that I was a gay boy. And one of them said, ”Oh, you’re transgender.” I’ll never forget it — he turned to me and said, ”Well great, I’m Frank Kameny.” From that day forward I always referred to Frank as my father. I love him so much because even though the GAA wasn’t for transgenders, it was for gay men, they never put me out. They made me feel like I was a part of something. And today, I love saying it: I’m an African-American transgender woman.

MW: What was the hardest lesson you learned on the street?

BUDD: Sex. Learning and understanding that I had to have sex with anybody, no matter who they were. And then there were times that I had to have unprotected sex. And I know today that it was through that avenue that I contracted HIV.

MW: How did you find out that you had contracted the virus?

BUDD: I was diagnosed in 1991, believing I was probably infected in the ’80s. We used to do shows at a club called the Brass Rail, and the Inner City AIDS Network was right around the corner from the club. They came and recruited people as peer educators to give out condoms and all of that. I volunteered, and I got certified as a peer educator. But I always knew that I had done a lot of things to put myself at risk of getting HIV. I never ruled out that in fact one day I might be diagnosed with HIV. In 1991, when I went to jail and got incarcerated again, they took my blood and came back and told me I was HIV-positive. I said, ”Okay.” And the doctor said, ”You’re not upset?” I said I wasn’t upset because I was a peer educator and I knew the facts. ”Now I just need to know what’s next,” I told him. ”What do you need me to do?” And they started me on [treatment with] AZT.

MW: How did you break your drug addictions?

BUDD: My drug problem was not to the level that it inhibited me from being functional. Even though I had a crack-cocaine problem, a PCP problem, I drank, and I did ecstasy. But I loved money so much — at some point I realized that I did not want my checks to keep going to the drug man, so I gave it up. In 1991, I decided that enough was enough.

MW: Do you think being locked up played a role in that?

BUDD: Absolutely. Those six or seven years that I went in, I really had a lot of time to think about life: Did I want to come back out and go through the same thing? I decided I would never go back. I will not have someone tell me when to eat and when to sleep. Today I only go back to help people out, because I know how hard it is. I know what the struggles are. I’ve been there and I’ve done that. But in this phase of my life, I have flipped the script and I know that I need to be there to help those who can’t help themselves.

MW: Did you ever contact your parents or siblings again?

BUDD: I still called my mom, especially as I started getting older. My mom was like any mother, she had some understanding. When I would call her, she would say, ”I love you so much, I don’t know why your dad and them won’t come around.” She passed away from kidney failure in the ’80s when I was about 25. I coordinated her services and I got to see my grandparents and cousins and folks. They were looking at me like, ”Who the hell is this coming to a funeral in female’s clothes?” My dad didn’t say a lot. I sat next to him and that was the first time he hugged me. I knew something had happened, but I didn’t find out till later what.

After my last offense when I was serving seven years for distribution, my dad had started connecting with me and sending me money. When I came out of prison in 1994, he was in a senior-citizen home and said he wanted to see me. I thought this was strange. It was a turnaround for him, something was going on. At that point, I had gotten my first job at the American Psychological Association, working for the behavior and social-science program, under Dr. John Anderson, and it was paying me pretty good. I was a volunteer for the HIV Community Coalition and at Whitman-Walker Clinic under Cornelius Baker, so I had really started establishing myself as an advocate.

My dad knew these were some of the things I was doing. When he met with me, he said, ”Of all the kids in the family, you’re one of the only ones that seems to be moving forward, even though we used to call you the black sheep. I’m so proud of you.” Then he told me the reason he had started sending me money was that before my mother died she had told him to love me. He said, ”She knew she was going to die and she said, ‘Don’t turn your back on him. He’s still our child.”’ That just tore me up. I hugged him and I told him I loved him so much. Then he told me he that he wanted to make me his beneficiary. I asked him if something was wrong and he said no.

All of a sudden I got a call that he was sick. I remember the doctor telling me that he was not doing well at all, that he was coughing up black stuff, that there were infections, and that he had assigned me as the person responsible for making decisions. I would visit him every day and tell him that I loved him. He was conscious and cognizant. Finally, in November, his primary physician asked me if he could do a bone-marrow test. When they did that, he called back the next day and said, ”Ms. Budd you need to come to the hospital right away.”

I came up to the hospital and sat down with this doctor and he looked at me and said, ”I have bad news for you. Your dad has terminal cancer, and it’s in his bones.” I just kept saying, ”Please don’t do this,” and then he told me that my dad wasn’t going to live beyond 48 hours.

I thought it was impossible. This was the person that had come back into my life and it was making such a difference. And now to know that I was only going to have him for such a short period of time — this couldn’t be true. I went in to visit my dad and I said, ”Daddy, you didn’t tell me the truth. You knew you had terminal cancer. You knew you were dying and you didn’t tell me.” And he just looked at me and said, ”Dying is only a thing. It’s a phase.”

I was on the Whitman-Walker board at the time, and we were having a board meeting within a day or so after I had seen him. My cell phone went off and I stepped out into the hall. They said, ”Ms. Budd this is the hospital, your dad just expired, and if you can make preparations and come over, we’ll prepare him so you can spend some time with him, because he would have wanted that.”

I guess I share that to say that even though being transgender in life we struggle with families being non-accepting, I think the crux of that is that it’s not that families don’t want to accept us, it’s just that we are different. And especially when you’re a male-to-female transgender and you’re born into a family as a male, the fathers normally expect to see boys going on and carrying their legacy and their names. I could feel that that’s what was going on with my dad. But at the end of the day, I can’t say anything bad about my dad because he came to love me and treated me like a human being and it was phenomenal.

MW: You’re still religious?

BUDD: I never gave up on faith. I came up in a Baptist church. That’s been embedded in me.

MW: Many LGBT people feel rejected by their faith. You didn’t?

BUDD: A lot of us are on the other side. We tend to pull toward Christianity, to Christ to be our savior, because we know that we can’t depend on our families. When I was incarcerated I called out. I sat on the bleachers, knowing I was HIV-positive and I cried. I said, ”God, if you get me out of this one, I will get out and do what you want me to do. I will not continue the life that I was doing out there.” In 1994 when I got out, it was a whole new life. I kept my promise.

Transgender Health Empowerment, the DC Trans Coalition and others commemorate the 2009 Transgender Day of Remembrance with speakers and a nondenominational ceremony, 6:30-9 p.m., at MCC-DC, 474 Ridge St. NW. Visit theincdc.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!