Greek Idol

In Master Class, Tyne Daly creates a remarkable presence, breathing life into a much-documented icon with great care

It is to Terrence McNally’s great advantage that three of his plays are being staged simultaneously at the Kennedy Center since anyone who sees only Golden Age, the labored 19th century backstage-at-the-opera drama, would never believe him capable of the far superior Master Class. An intriguing, well-crafted piece about the life and career of überdiva Maria Callas, Master Class is an entertainment that transports. McNally not only gives us a tangible complex personality, he captures something real and true about what it is to sing opera.

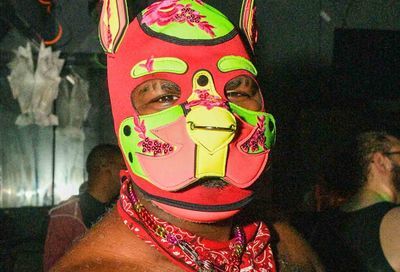

Tyne Daly in Master Class

(Photo by Joan Marcus)

As the title suggests, the play consists of a master class in which Callas puts several students through their paces while critiquing them before an audience (us) of aspirants and aficionados. Callas did give several such classes at the end of her career, but McNally’s is not a reenactment, it is a jumping-off point for an exploration, with dramatic license, of what drove Callas as an artist and a woman.

Though she is prickly, undermining and ruthless with her wit, we see here, through her anecdotes and reveries, that Callas’s hardness is intertwined with an essential vulnerability and the lasting wounds of a complicated life. And though she may torture her students, she nevertheless strives to push each one of them to a higher plane of understanding and thus performance. With restraint, rhythm and a powerful ability to evoke mood and place, McNally paints this woman with increasing detail as the class progresses. And yet, to his credit, he does not fill in every space or draw every line — Callas maintains her mystery, even though we learn much about her. And indeed the accuracy of what we learn matters less than the power and clarity of the vision McNally brings to his portrait of this legendary woman.

As with Golden Age, McNally is still writing for a mainstream theatrical audience. The polish, the more obvious jokes, and the presence of the simpering Manny, Callas’s accompanist, all speak to the needs of the theatrically spoon-fed. But with so much of interest also going on in this piece, such cons are tolerable.

As Callas, Tyne Daly creates a remarkable presence, breathing life into the much-documented icon with great care. Though she has fun with the quirks and dramatics, she balances them well with the deeper melancholy, despair and damage that reside in McNally’s Callas – we feel the connection between the witty, sharp-tongued teacher and the long-ago heartbreaks that served to form her carapace. And though there are times when McNally gilds the diva lily, Daly manages to dampen the effect with an air of credibility and understatement.

Interestingly, in a construct such as this, it must be said that part of the magic of Daly’s performance is also the undeniable fact that it is Tyne Daly being Maria Callas. As Callas teaches her singers to sing with an actor’s concept of embodiment, Daly shows us what it is to embody. Elsewhere, such a layer would break a necessary fiction; here it works as the perfect reflection of the fiction Callas made of herself, the fiction her public made of her, and the way all celebrities must contend with the concept of persona.

It also gives us two roles as audience; Callas’s audience and Daly’s, and that toying with our perceptions is clever and provocative. And yet when Callas steps away from her students and falls back through time to re-live pivotal moments in her life, Daly, being the accomplished actress she is, disappears to leave Callas alone on the stage.

Serving as sidekick and pianist is Jeremy Cohen as Manny, a man willing to suffer Callas’s casual abuse for the chance to share the stage with the legend. Cohen reasonably complements Daly’s Callas, but he cannot buck the hokey qualities of the role as written and thus often sets the teeth on edge. Although each singer-student learns something about themselves under Callas’s harsh hand – and we learn something about Callas – director Stephen Wadsworth finds no way to give the pairings frission.

To April 18

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

$25-$80

202-467-4600

kennedy-center.org

Indeed, the only moments that matter are when Callas stops interacting and begins to teach; then, through Daly’s skill, we begin to see what McNally has to tell us about Callas, her art and opera as a whole — and t hat is what remains compelling, unique and memorable.

Of the singer-students, Laquita Mitchell, playing and singing (very nicely) the Second Soprano, generates the most energy with Callas, although it is hard to tell where her timidity ends and her toughness begins. Ta’u Pupu’a as the Tenor has a kind of verite credibility, but his nascent interplay with Callas stalls out when McNally inexplicably makes her listen instead of teach. As the First Soprano, Alexandra Silber over-cooks her newbie but still serves as a good foil for some of the diva’s better one-liners. Finally, Clinton Brandhagen as the stagehand who occasionally lumbers into the highbrow proceedings, just about covers the ground, but as with the others he never quite generates the necessary sparks with Callas.

Still, this is a haunting, intelligent and original play with much to say about the artistic process. Opera 101 not a prerequisite.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!