The Next Generation Awards 2010

Some people turn to drinking and partying to cope with heartbreak. Harjant Gill turned to filmmaking.

”When I started college, I was all set to be a biologist, like a good Indian son,” says the 28-year-old, who went to San Francisco State University. ”But I went through this devastating heartbreak my freshman year. The first guy I was in love with, he really broke my heart.”

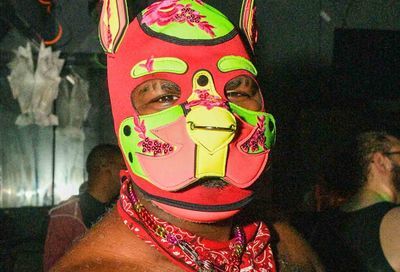

Harjant Gill

Harjant Gill

So Gill, whose interest in filmmaking had been piqued a few years prior by the ”moving and powerful” work of Indian-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta (Fire), signed up for a filmmaking class for gay and lesbian youth offered by a San Francisco community center. And out of that class came Everything, Gill’s first short film.

”To this day it remains a film that has played the most out of all my films,” says the American University adjunct professor of anthropology. Gill has gone on to make a half-dozen films, mostly documentaries, many of which have played the festival circuit.

”Film has an incredible ability to really inform people and sort of change their opinion, or create a climate for change,” says Gill, who is certainly helping create such a climate. He was recognized as one of 30 youth worldwide creating change in their communities profiled in the International Youth Foundation’s 2002 book Our Time Is Now. Since 2006 he’s been distinguished as a Point Foundation Scholar. And now, he adds a Metro Weekly Next Generation Award to his credits.

”I grew up feeling like I was constantly being victimized by society because I’m gay, and because I came out at an early age,” says Gill, who moved to the U.S. from India with his family when he was just shy of 14. He came out to his parents a year later. ”I felt like I was fighting against the system at all times.”

The Next Generation Award builds on the earlier support that helped to change Gill’s feeling of victimization, particularly the Point Foundation’s fellowship.

”The Point Foundation gave me the opportunity [to go to grad school] and provided the emotional support and really a sense of family and mentorship,” he says. ”I was able to break out of this victim mode because they nurtured and supported me.”

Gill says his siblings, an older sister and a twin brother, ”have been really incredibly supportive about me being gay. I think in some ways, even though they’re not gay, they were able to break out of the sort of traditional ideas about what it means to be Indian, or living in an Indian family, because they saw me doing it.” Gill’s sister now lives in Las Vegas while his brother actually lives with him in D.C. He works as a nurse at the National Institutes of Health. ”We’re identical twins but we’re complete opposites of each other,” he says.

Meanwhile, his parents in San Francisco ”are actually very excited about my film work for the first time.”

The new excitement was sparked by a commission from an Indian national television station to make a documentary focused on his ancestral Punjabi region.

”My mom has been calling me, giving me all sorts of ideas about how I should make my documentary,” which is on the broader subject of gender and masculinity. Gill, who grew up a Sikh but now considers himself closer to Buddhism than any other religion, says Punjabi culture embraces a machismo similar to what might be found in traditional Latino culture.

”Sikh men are considered to be the alpha males of India,” Gill explains. “As a consequence, Sikh communities are hesitant or resistant to accepting gay and lesbian identities and people.” Still, he adds, ”there isn’t any direct animosity [toward gays] — there’s nothing in the scriptures or any of the texts that condemns homosexuality.”

Prior to this project, Gill says his parents had seen some of his films, but had expressed dismay that he was so public about being gay. ”The issue of sexuality is always a touchy subject in my family,” he says. ”Just sexuality in general, not just being gay or straight. We don’t talk about sex.”

But sex and sexuality is increasingly being broached in India, where the government finally decriminalized homosexuality last year. ”It’s an exciting time in India,” says Gill. ”You see a lot of films now coming out dealing with gay themes. Before they would just hint at two people having something.”

Gill’s doctoral dissertation explores another Indian theme, examining a relationship between north Indian cinema and migration. ”People construct their notions about migration, work, labor and a sense of their gendered selves based on what they see on the cinematic screen,” he says, ”because film is such a huge cultural component of life in India.”

Gill is fascinated by the notion of migration and specifically what drew his parents to move halfway round the world. He has long wondered ”what would compel somebody to give up their entire life, their family, their entire community and kinship network and move to a completely strange place?”

Gill plans to continue in academe full time even after earning his doctorate next year. ”I really enjoy teaching. Every time I go to class, it’s like I can forget about the rest of the world,” he says. Plus, anthropology is ”an investigation into everything. It’s always brought me closer to understanding the world.”

But a part-time future in filmmaking is also a given, and Gill considers the art a type of ”applied anthropology.”

”I don’t think I can stop making films,” he says. ”I tried that last year, and now I’m going back to India to make this film. I just don’t want to be at a point where I rely on film as a means of income. I want to do them because I’m passionate about them.”

And he’s long since recovered from that initial heartbreak. Gill has been dating a guy, Nick, ever since he got back in January from a year in India. ”I’m really thankful to have him in my life.”