The defense was no surprise on Jan. 13.

The Department of Justice had announced in October its plans to appeal the July decisions striking down section three of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) as unconstitutional.

The filing of its appellate brief in Gill v. Office of Personnel Management and Massachusetts v. United States before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, though, signaled how the administration has changed in the two years since President Barack Obama took office. It also was a sign of the limits to, as the president himself put it recently, any evolution on marriage equality at this time.

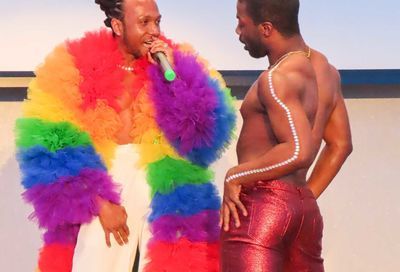

![President Barack Obama with Vice President Joe Biden [left]](/articles/attachments/2010-12-23_feature_story_5879_5905.jpg) President Barack Obama (Photo by Ward Morrison/Metro Weekly)

President Barack Obama (Photo by Ward Morrison/Metro Weekly)

For more than a year and a half, the Obama administration has been faced with an unenviable quandary: Defend laws Obama says are discriminatory, like DOMA and ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” or don’t defend those laws and explain why it is picking and choosing which laws the executive branch chooses to defend.

Because the laws have been around for about 15 years and upheld by a number of federal courts, however, a decision by DOJ not to defend the laws would have been highly unusual – though experts disagree as to whether it would have been unprecedented. What’s more, Obama – while calling for the repeal of both laws – has refused to say in recent months whether he believes they are unconstitutional. Were he to do so, particularly after losing at the trial court, that would give DOJ a basis – however thin – for refusing to defend an otherwise validly enacted law on appeal.

The defense of DOMA has put the administration on the defensive with an expanding circle of LGBT activists and some allies since the Justice Department filed a brief defending the law in a federal trial court in California in Smelt v. United States on June 11, 2009.

The Smelt brief, which referred on more than 10 occasions to the ”traditional” definition of marriage, was met with strong opposition from the LGBT community. Most strikingly, the Smelt brief declared, ”DOMA does not discriminate against homosexuals in the provision of federal benefits.”

Across the country, in another case challenging a part of same law, U.S. District Court Judge Joseph Tauro disagreed. A year after the Smelt filing, Tauro found in Gill v. Office of Personnel Management and Massachusetts v. United States that the law does discriminate against homosexuals. He found that the federal definition of ”marriage” and ”spouse” – traditional or otherwise – violated the constitutional requirement of equal protection of the laws because ”irrational prejudice plainly never constitutes a legitimate government interest.”

In the Jan. 13 appeal, though, some of the Obama administration’s top lawyers – including Assistant Attorney General Tony West, who heads the department’s Civil Division – argued that DOMA was constitutional and was motivated by something other than irrational prejudice.

The basic argument advanced by DOJ – that DOMA made sense, or is rational, because the states hadn’t reached a uniform decision about same-sex marriage in 1996 – has not changed much since Smelt.

The changes that have been made, though, presumably reflect a greater understanding at Justice of the president’s policy views on this issue. For example, there are no longer any references to a ”traditional” definition of marriage in the brief.

Also, perhaps, the brief simply represents a decision by DOJ’s lawyers that this is the path to take to have the best chance of succeeding in defending the law. The more nuanced language could reflect what DOJ lawyers appear to believe is a less discriminatory, and thus more likely constitutional, enforcement of DOMA.

For example, in arguing that section three of DOMA is constitutional and simply was ”maintaining the status quo,” DOJ asserted on Jan. 13 that the law was passed ”during a period of change” and ”would allow states that wish to make changes in the legal definition of marriage to retain their inherent prerogative to do so, while permitting others to maintain their existing view.”

Just one-and-a-half years earlier, DOJ had expressed what is, essentially, the same idea very differently. Then, DOJ argued that DOMA was ”preserving a longstanding federal policy of promoting traditional marriages” and that would ensure that federal laws ”do not encompass relationships of any other kind within their ambit.”

Should we, as a nation, recognize same-sex marriages within our understanding of marriage or not? Between 2009 and 2011, the Department of Justice changed its tone and eliminated any implicit approval of the decision by a state – or Congress – to keep that ”traditional” definition and reject same-sex marriage.

In a way, then, this is a step forward.

DOJ did, however, keep defending the law. And, what’s more, it did so in a way that ignores the plain discriminatory intent of those members of Congress who passed the law in 1996.

As the House Judiciary Committee report on DOMA makes clear, the law was passed – as its supporters on the committee wrote – because of ”the orchestrated legal assault being waged against traditional heterosexual marriage by gay rights groups and their lawyers.”

Rather than defending the actual reasons stated by Congress for passing the law, the administration instead argued in its Jan. 13 brief, ”As the GAO concluded, there are over a thousand federal laws implicated by DOMA, showing that the federal government undoubtedly does have a substantial interest in determining eligibility for benefits under federal laws and programs that may touch upon family relationships.”

In downplaying the discriminatory intent of the law, DOJ has taken an argument used for the past 15 years by equality advocates as a reason why marriage equality is needed and turns it on its head. Anti-gay animus, and no ordinary decision about ”benefits,” was the basis for the passage of DOMA.

Although DOJ’s Jan. 13 filing defending section three of DOMA represented a kinder, gentler view than that offered by the government in 1996 or even 2009, it cannot erase the discriminatory intent or impact of the law that led Judge Tauro – though not yet President Obama – to decide that it is unconstitutional.

![President Barack Obama with Vice President Joe Biden [left]](/articles/attachments/2010-12-23_feature_story_5879_5905.jpg)