Becoming Law

On Sept. 21, 1996, President Clinton signed DOMA into law – a turning point for the marriage debate that left a mark of discrimination still on the books

by Chris Geidner

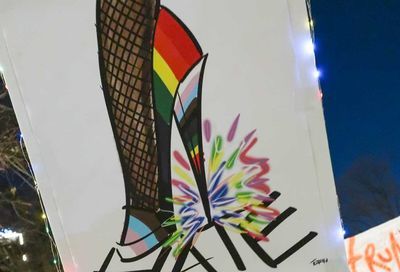

Illustration by Scott G. Brooks

September 29, 2011

The conclusion of a four-part series marking the 15th anniversary of the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act

By the time the Senate passed the Defense of Marriage Act on Sept. 10, 1996, there was no question what President Bill Clinton was going to do when the bill was presented to him.

Months earlier, May 23, 1996, Clinton made his first comments on DOMA, jumbling the specific effect of the bill but echoing comments from his press secretary that he would sign it. On July 11, 1996, the administration issued a Statement of Administration Policy: ”The President … has long opposed same sex marriage. Therefore, if H.R. 3396 were presented to the President as ordered reported from the House Judiciary Committee, the President would sign the legislation.”

Bill Clinton and the Defense of Marriage Act

(Illustration by Scott G. Brooks)

But, asked if that was the only path, people around at the time — from LGBT advocates to Clinton staffers — almost universally say no. As the then-head of the Human Rights Campaign, Elizabeth Birch, says of the impact of a Clinton veto of DOMA at the time, ”He could have survived it. Absolutely.”

Paul Yandura, who worked in the White House gay and lesbian liaison’s office at the time, puts Clinton’s decision to support DOMA in stark terms.

”He could have said, ‘Look, I’m just going to veto this.’ If you look at the polling around that time, he was way ahead in the polls. And so, could he have taken a five-point dip? Sure. Were we worth it? I guess they decided that we weren’t.”

Yandura sees the decision as a political one. That view is shared by Richard Socarides, the Labor Department’s White House liaison when DOMA was introduced in the House in May 1996, but became the White House liaison to the gay and lesbian community in the midst of the debate over DOMA. Socarides says, ”It was clear to us from the first moment we heard about it that it was a Republican Party campaign stunt to box Clinton in and to give them something to run on against him, and they were very, very clear on that.”

But for former Sen. Tom Daschle, then the Senate Democratic leader, and the 32 Democratic senators who voted for it, DOMA was essentially the lesser of two evils — he says they considered a constitutional amendment to restrict marriage to be almost ”inevitable” at the time.

”There was a strong movement to pass a constitutional amendment to put in constitutional law the notion that marriage is between a man and a woman. And the concern that many of us had was that you couldn’t beat the constitutional amendment,” he says. ”So, you had to come up with an alternative to a constitutional amendment and argue that this was better for all concerned. And that was a big part of the tactical and strategic decision-making that went into the run-up to the vote itself.”

As to whether the Republican presidential politics of Bob Dole — the Senate majority leader at the time of DOMA’s introduction — were key, Daschle says only, ”I would defer to others on that. I don’t remember that part of it.”

Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.) does. He says politics were at the center of DOMA, noting of Dole’s campaign, ”They were lagging behind Clinton, and they saw this as a classic wedge issue. They saw it as a way to force Clinton to either take a position that would be unpopular in the country as a whole – or alienate gay people. It was all the Dole campaign.” Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.), who led the Senate opposition to DOMA, said as much at the time, calling the bill the ”Endangered Republican Candidates Act” in his opening statement in the July 11, 1996, Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the bill. He went on to say of DOMA’s intrusion of state regulation of marriage, ”I assume that Bob Dole’s copy of the 10th Amendment has a new hole in it.”

Daschle’s argument — that DOMA was stopping something worse — doesn’t fit with the recollections of most LGBT advocates engaged in the debate at the time. Evan Wolfson, who was then running the National Freedom to Marry Coalition while a lawyer at Lambda Legal, says, ”That’s complete nonsense. There was no conversation about something ‘worse’ until eight years later. There was no talk of a constitutional amendment, and no one even thought it was possible — and, of course, it turned out it wasn’t really possible to happen.

”So, the idea that people were swallowing DOMA in order to prevent a constitutional amendment is really just historic revisionism and not true. That was never an argument made in the ’90s.”

”You Never Know What Would Have Happened”

Although the constitutional amendment may not have been the central question as Daschle remembers, it is clear that, as Yandura puts it, Clinton’s decision to support DOMA ”was a political decision that they made at the time of a re-election.”

Socarides explains, ”Presidents make tough calls all the time, and I think that there were people advising the president – the president had a group of political advisers who, at the time, actually believed that if the president had vetoed the bill, that his re-election would be jeopardized.”

He adds, ”I did not believe it then, and I think history has proven those advisers wrong. But they actually believed it at the time – and I convinced myself at the time that they actually believed it and that there was no convincing them otherwise. That’s not to suggest that the president’s political advisers thought it was a good idea. Nobody was happy about it. But there were many more people who were resigned to it than were outraged by it.”

Why many advisers were, at best, resigned to Clinton’s signing DOMA into law, in Andrew Sullivan’s mind, it also raises a question about LGBT advocacy at the time. Looking back, he says that he and Wolfson had more freedom to address the issue than groups like the Human Rights Campaign and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

”We didn’t have to tell our paymasters and our funders and our fundraisers that we were doing all of this only to lose. They don’t like that – it’s institutionally not the way lobby organizations want to run. They don’t want to tell their memberships, ‘I’m sorry we’re losing, but it’s good for us.’ They would rather avoid anything that could lose, wait until they got something that they knew could win,” Sullivan says. ”My point was, ‘No, no, no, we wait for-fucking-ever if we do that. So, let’s get it out there. I’m sure we’re right. I’m sure we have the better arguments.’ And that was Evan’s position, ‘Let’s just face this down.”’

Yandura — who says that he thought at the time that the organizations’ positions made sense — now agrees that stronger pushback could have mattered: ”You never know what would have happened if they would have said, ‘No, fuck you. We’re not taking DOMA. We ate ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.’ … You know what? You’re going to take a hit. You know what? You have really smart people around you, figure out how to politically do this.’ You just never know what would have happened if HRC and NGLTF said no.”

Birch, though, says, ”That’s silly. We went at it tooth and nail. It was like hand-to-hand combat. It was extremely painful.”

”The idea that we couldn’t pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, but we were going to somehow be able to stop DOMA, it’s folly in its analysis,” she says. ”One of my largest fights when I was at the Human Rights Campaign was with [the late Sen.] Paul Wellstone (D-Minn.). Beloved, almost a folk hero in terms of progressive policy. But he voted for it. And he said, ‘Don’t you want me here to fight for other things?’ And I said, ‘No, because if you vote for this, you will no longer be Paul Wellstone.”’

Socarides defends HRC’s efforts, saying, ”As someone who was there – and I’ve had my differences with Elizabeth Birch and with HRC – they fought and she fought extremely hard over this. As someone who was in touch with her every day, pretty much every day during this period, she was an – probably the hardest – extremely determined and effective advocate against this bill. She was very clear, both in person and in writing, on the grave consequences to the country, really, and to President Clinton’s reputation in history and very clear that the stakes could not have been higher.”

Although she opposed Clinton’s decision, Birch notes the abrupt and successful way he eliminated the issue from the campaign: ”Clinton moved very expertly and took it out of play – but it was incredibly painful. There wasn’t even a chance for discussion.”

To those who say there was no way Clinton was going to announce that he would veto DOMA in the midst of the 1996 re-election campaign, Wolfson says, ”I don’t agree with that. I think we are entitled to demand much more of politicians, and I think it would have been in Bill Clinton’s interest to do that. There’s always been this failure to appreciate that the American people like politicians who stand up for what they believe in and who make a case, particularly when it’s something ultimately that most of them either don’t care about or can understand in a different way if given a way to understand it.”

Despite the attempts, such as they were, inside and outside the White House to push Clinton in any different direction on DOMA, Yandura says that by time the bill was introduced in May 1996, the debate already had turned to a question of semantics.

”At that point, it was like, ‘How are you going to talk about it?”’ he says. ”There was no more, ‘We can stop this. We can sidestep it.’ I know that we were all hoping inside, and there were conversations, but [no].”

By the summer of 1996, as Democrats prepared to head to Chicago in August to re-nominate Clinton and Vice President Al Gore, the decision on DOMA already was established and publicized.

Socarides notes, ”It was extremely discouraging, but once you knew a decision had been made, it was time to move on. We were in the middle of a re-election, and in politics it’s always about the alternatives, and the alternatives we knew were going to be far worse, and it was time to move on and get the president re-elected.

”That was my job.”

On Aug. 29, 1996, Clinton accepted his nomination and addressed the Democratic National Convention.

”Look around this hall tonight, and to our fellow Americans watching on television, you look around this hall tonight — there is every conceivable difference here among the people who are gathered,” the president said. ”If we want to build that bridge to the 21st century we have to be willing to say loud and clear, if you believe in the values of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, if you’re willing to work hard and play by the rules, you are part of our family and we’re proud to be with you.”

Going on to say, ”We still have too many Americans who give in to their fears of those who are different from them,” Clinton then said, ”So look around here, look around here — old or young, healthy as a horse or a person with a disability that hasn’t kept you down, man or woman, Native American, native born, immigrant, straight or gay, whatever; the test ought to be I believe in the Constitution, the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence.”

Yandura points to that as a significant moment, saying, ”I think a turning point for him was when he went to the convention and talked about gays and lesbians. All he did was say, ‘Look out there, look across the room, you see … gay and straight.’ He didn’t say, ‘I’m for gay marriage’ or ‘I’m gonna go further.”’

Saying how different a time it was then, Yandura continues, ”That’s all he said, and after that, you can see, the press turned,” referencing what he perceived at the time as a decreased focus by the press on a ”rift” between Clinton and the gay and lesbian community.

”And we were raising money [from gay and lesbian donors],” he also notes.

As the money was raised and the campaign continued on, Dole — the man many say was at the center of DOMA’s introduction — was out on the campaign trail full time, having resigned from his Senate seat in June 1996. As such, when the Senate voted to pass DOMA on Sept. 10, 1996, Dole was no longer a senator and didn’t even cast a vote on the bill.

”I Am Signing Into Law H.R. 3396”

Ten days later, Sept. 20, 1996, the bill passed by both chambers of Congress was sent to the White House and ”presented” to the president.

At that point, Clinton had 10 days to sign the bill.

The White House Press Office released a statement from the president, in which he said, ”Throughout my life I have strenuously opposed discrimination of any kind, including discrimination against gay and lesbian Americans.”

Then: ”I am signing into law H.R. 3396, a bill relating to same-gender marriage, but it is important to note what this legislation does and does not do. I have long opposed governmental recognition of same-gender marriages and this legislation is consistent with that position.

”This legislation … has no effect on any current federal, state or local anti-discrimination law and does not constrain the right of Congress or any state or locality to enact anti-discrimination laws.”

Clinton’s statement closed: ”I also want to make clear to all that the enactment of this legislation should not, despite the fierce and at times divisive rhetoric surrounding it, be understood to provide an excuse for discrimination, violence or intimidation against any person on the basis of sexual orientation. Discrimination, violence and intimidation for that reason, as well as others, violate the principle of equal protection under the law and have no place in American society.”

Much has been made of the way he signed it.

”President Clinton waited until the dead of night yesterday to sign legislation aimed at preventing gay marriages, timing his action to minimize public attention and contain any political damage just 45 days before the election,” The Washington Post‘s Peter Baker reported at the time. Socarides says that the ”dead of the night” legacy of Clinton’s signing is slightly overstated.

”He didn’t sign it in the middle of the night to try and hide it from anybody,” Socarides says.

”The reality behind that story was that a decision was made that, if he was going to sign the bill, he should sign it as soon as he could. Just to sign it and get it done with so that we could put as much time between the actual election and his signing of the bill,” he says. ”On the day it arrived at the White House, the president was traveling — he was in the Midwest. So, when he got home they put it in front of him and he signed it.”

At 12:50 a.m., Sept. 21, 1996, in the early hours of a Saturday, the president signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law.

Although some advocates involved at the time were able to understand the president’s desire to get the bill off the table to diminish the issue’s impact on the fall elections, a mid-October 1996 advertisement run by the Clinton/Gore re-election campaign showed how strained the relationship between the gay, lesbian and bisexual community and Clinton had become in the wake of DOMA.

Yandura, who had left the White House to run gay and lesbian outreach for the re-election campaign, says, ”I was in my office at the re-elect, and I got a call from [then-HRC communications director] David Smith, irate as shit, like, screaming at me, and I didn’t know what happened because no one told us.”

What had happened was that the campaign had responded to an ad from the Dole campaign questioning Clinton’s values by running an ad of its own on Christian radio stations touting Clinton’s signing of DOMA, as well as proclaiming his support for laws banning late-term abortions.

”I got a copy of the ad and it really was, ‘Oh, don’t worry, we don’t like the gays either, we’re against the marriage thing.’ There was no possible way that if anyone would have seen that — in my office or Richard or any of us — that it would have ever gotten through,” Yandura says, noting that he considered quitting over the ads. Talking about the difficulty of explaining ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and DOMA itself to gay, lesbian and bisexual voters, he says, ”I felt like we used a lot of political goodwill to get where we were. This was the last straw. When I heard them myself, I remember my heart sunk and I just thought, ‘I can’t do this, I just can’t do this.”’

Yandura says, ”We were being told to tell the public that the ad agency made them and they weren’t approved by the campaign. I refused … because that was clearly not the case.” When campaign staff like Yandura didn’t believe that explanation, he says the campaign ”wound up pulling them, which, I’m glad they did.”

Frank, the out gay representative from Massachusetts, also heard about the ads — and says he ”raised hell” with his sister, Ann Lewis, who was the communications director for the Clinton/Gore campaign: ”I called my sister and said, ‘What the hell are you guys doing? You can’t do this,’ and it got pulled. But it shouldn’t have been on in the first place.”

Yandura adds that if people like he and Frank hadn’t complained, the ads likely would not have been pulled. ”If we would have said, ‘Okay, that’s fine, it’s the religious right,’ they would have probably played them.” The ad was pulled, the country moved on, and, on Nov. 5, 1996, William Jefferson Clinton won re-election, handily defeating Bob Dole and garnering more than double the electoral votes of the former senator from Kansas.

The Defense of Marriage Act, meanwhile, had become the law of the land.

”It Was Like a Checkmate”

In less than five months, the Defense of Marriage Act went from an idea to a federal law.

Nonetheless, the lawsuit in Hawaii that had launched the debate in Congress continued forward. The case brought by Ninia Baehr, Genora Dancel, Tammy Rodrigues, Antoinette Pregil, Pat Lagon and Joseph Melilio led to the historic decision on Dec. 3, 1996, that Hawaii’s refusal to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples was unconstitutional under the state’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws.

The Hawaii trial court found that the state had failed to prove what the state Supreme Court had ordered it to prove: that the marriage law’s ”statute’s sex-based classification is justified by compelling state interests” and was ”narrowly drawn to avoid unnecessary abridgments of the applicant couples’ constitutional rights.” Toward the end of the decision, after reviewing all of the evidence that had been presented by the plaintiffs and the state, Judge Kevin S.C. Chang concluded: ”[T]he evidence presented by Defendant does not establish or prove that same-sex marriage will result in prejudice or harm to an important public or governmental interest.”

For Evan Wolfson, the decision was exactly what was needed to offset DOMA’s passage. Co-counsel on the case with Dan Foley, a local Hawaii attorney the couples had found to represent them in 1991, Wolfson says of the decision, ”I wrote at the time … that the earth had just moved, that this was a tectonic shift in our movement, in our country’s history, in the conversation about marriage and that we now had the American people’s ear and could talk about who gay people are and why marriage matters in a way that was going to profoundly change things.”

He adds that this conversation would benefit other efforts, in his view, because, ”A deeper understanding would show that marriage has always been a battleground on which larger questions of inclusion and equality and freedom and what kind of country this is going to be have been contested.”

But the victory did not lead to marriage equality in Hawaii. A constitutional amendment was proposed to and, in November 1998, passed by voters that allowed the Legislature to ban same-sex marriages in the state.

And, on the federal level, DOMA was a painful loss that stuck in people’s minds and, advocates say, altered the debate.

Elizabeth Birch calls DOMA and the Hawaii amendment ”horrifically difficult battles that were enormously expensive,” and adds, ”We did pay a price at the federal level in that we could not achieve other things. It ended up coming in and really scooping out the vestiges of any force that the Democrats had or any conviction to get anything done – and so nothing got done. But I blame the Republicans — who played it like a massive chess game, and it was like a checkmate.”

HRC’s legislative director at the time, Winnie Stachelberg, says, ”I think it set us back significantly, from a number of vantage points. I think it was deflating for our community. It was hurtful. I think, politically, it opened the door for the state DOMAs, the state super-DOMAs … an all-out assault of anti-gay initiatives. Congress passed and the president signed a piece of legislation that people say should be repealed and is unconstitutional — and yet, at the time, it passed so overwhelmingly, with support from purported allies.”

Birch adds of the anti-gay Republicans, ”They won. They used it. And then they used it over and over and over again. Honestly, I think it’s been [only in] the last couple of election cycles where it’s just been wrung out. It’s just not potent anymore.”

From a lawmaker’s point of view, Barney Frank says that DOMA ”forced people to commit prematurely, so that a lot of members of Congress and other elected officials had to commit against marriage. That wasn’t helpful to us.

”We really couldn’t make the argument in favor of same-sex marriage until we had it,” he says, pointing to the emergence of marriage rights in Massachusetts and other states as important changes in the political landscape. ”What’s changed the fact of this debate is that we had marriages and nothing bad happened. Reality beats fiction, but in the absence of reality it’s hard to do that.”

That debate in 1996 was an essential part of creating the reality of the successes since, says HRC’s political director at the time, Daniel Zingale: ”It was certainly a moment of maturation for us in experiencing for ourselves what our new allies in the civil rights movement were telling us, which is that the road to equality is a long struggle. And, just because you’re right, you don’t get what you know you deserve when you know you deserve it.”

Looking back over those successes and failures of both movements, Andrew Sullivan sees a similar, if more active, message.

”We have to use our defeats as ways of educating and illuminating,” he says. ”And we’ve got to take risks. And we’ve got to be able to lose in order to win.”

Richard Socarides, who continued to serve as President Clinton’s gay and lesbian liaison after DOMA’s passage, adds, ”I think what made it easier to move on was that nothing changed; the law was signed and nothing changed. What made it easier to move on is that [because] you couldn’t be married anywhere, no one was immediately affected. The fact that no one was immediately affected, that made it easier to move on.”

Wolfson agrees, to a point, saying, ”Evil and discriminatory as DOMA is, it does not prevent states from taking steps to end marriage discrimination and that’s precisely where we need to focus our efforts — and that’s, of course, where we did focus our efforts.”

It was the success of those efforts — the marriage equality case in Massachusetts in 2003 that led to same-sex marriages there in 2004 — that showed DOMA’s teeth, Socarides says: ”We only saw later, almost eight years later, only began to see the real damage of the legislation.”

As same-sex couples began marrying in Massachusetts and eventually elsewhere, federal benefits – from government employees’ spousal health insurance to Social Security survivor benefits – began being denied to partners in those marriages. As same-sex partners began to end their legal relationships, questions about the way the other states would treat the end of those relationships arose from Virginia to Texas.

In those and many more situations popping up across the country, the real impact of DOMA began to become clear to people everywhere. Its original supporters, from the lead House sponsor, Rep. Bob Barr (R-Ga.), to Daschle and Clinton, turned on the legislation: All three support repeal of the 1996 law.

And, for people like Mary Bonauto, who was the lead attorney for Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders in the Massachusetts marriage case, a path forward – a path to dismantle DOMA – began to form.

Part 1: Domestic Disturbance

Before DOMA, there was another debate over marriage – within the gay and lesbian community

Part 2: Marriage Wars

In 1996, DOMA went from being introduced to being passed by the House – and given the OK of the Clinton administration – in less than 10 weeks

Part 3: Double Defeat

In 1996, ENDA was hoped to help ease the pain of DOMA, but instead fell by one vote in a Senate focused on a ”thinly disguised example of intolerance”

Part 4: Becoming Law

On Sept. 21, 1996, President Clinton signed DOMA into law – a turning point for the marriage debate that left a mark of discrimination still on the books

‘A Nice Indian Boy’ Spares No Layer of Sentiment

A blandly sweet gay romance, "A Nice Indian Boy," starring Karan Soni and Jonathan Groff, looks great but lacks buoyancy.

By André Hereford on April 5, 2025 @here4andre

Like a warm hug wrapped in a warmer turtleneck, A Nice Indian Boy spares no layer of sentiment limning the love story of two nice Indian boys, Naveen and Jay.

Actually, Jay, played by Looking's Jonathan Groff, is a white American orphan who was adopted and raised by an older Indian couple.

They've since passed on, but Jay is still the nice Indian boy whom Naveen (Karan Soni) brings home to meet his traditional parents, Megha (stand-up comedian Zarna Garg) and Archit (Harish Patel), and his moody older sister, Arundhathi (Sunita Mani).

The featured meet-the-parents encounter follows a generously paced first act, in which hospital doctor Naveen and professional photographer Jay almost meet-cute praying in front of the Ganesh altar at a Hindu temple. It's practically love at first sight, a mutual epiphany of interest and attraction that Soni and Groff make both cute and credible.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

The Magazine

-

Most Popular

Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban

Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban  Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer

Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer  Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal

Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal  Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures

Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures  White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures

White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures  Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya

Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya  Charges Dropped in Nancy Mace Assault Case

Charges Dropped in Nancy Mace Assault Case  White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"

White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"  'Porn Star University' Started by Gay-for-Pay Creator Andy Lee

'Porn Star University' Started by Gay-for-Pay Creator Andy Lee  WorldPride Warns International Trans Visitors About Travel Risks

WorldPride Warns International Trans Visitors About Travel Risks

Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban

Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban  White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures

White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures  White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"

White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"  Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures

Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures  Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer

Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer  'cullud wattah' is a Compelling Drama About Flint's Toxic Water

'cullud wattah' is a Compelling Drama About Flint's Toxic Water  Gay French Thriller 'Misericordia' is Creepy and Suspenseful

Gay French Thriller 'Misericordia' is Creepy and Suspenseful  Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya

Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya  This Week's Advertisers: Rep. Becca Balint - April 10, 2025

This Week's Advertisers: Rep. Becca Balint - April 10, 2025  WorldPride Warns International Trans Visitors About Travel Risks

WorldPride Warns International Trans Visitors About Travel Risks

Scene

Metro Weekly

Washington's LGBTQ Magazine

P.O. Box 11559

Washington, DC 20008 (202) 638-6830

About Us pageFollow Us:

· Facebook

· Twitter

· Flipboard

· YouTube

· Instagram

· RSS News | RSS SceneArchives

Copyright ©2024 Jansi LLC.