Checked Out

Gay man claims hostile environment at the Library of Congress after being outed

On one hand, the Library of Congress is the institution that houses a large portion of the late gay-rights icon Frank Kameny’s legacy – despite criticism from anti-gay activists. It’s a federal institution that since 2009 has celebrated LGBT pride in June.

On the other, the Library of Congress has faced a class-action suit filed by black employees claiming a culture of discrimination. In 2008, Diane Schroer, a transgender woman, won a sex-discrimination suit against the library.

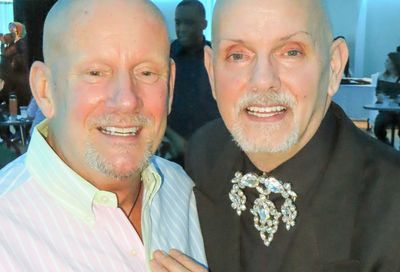

Peter TerVeer

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Peter TerVeer, a gay man, says he’s seen far more of that discriminatory landscape than of any embrace of LGBT employees. Enough, in fact, that he filed a discrimination complaint and is preparing to sue.

”The physical effects, the emotional distress it’s been causing me, has been out of this world, more so than anything I’ve experienced before in my life,” says TerVeer, 30, sitting in the shadow of the library’s colossal Madison Building, in which he once worked. ”I was put on disability back in October – but leave without pay disability. I haven’t received a check from them since. I’m basically bankrupt at this point. I’ve got $12 to my name. I’m making preparations to go back to [my family in Fremont,] Michigan. I can’t afford it here anymore. I’ve tried to move on, to get another job, to get out of this. I’ve appealed the decision of them firing me. I don’t have the money to pay for my treatment, for my therapy.”

The distress, says TerVeer, began after his supervisor in the Office of the Inspector General learned he was gay. When he began the job as an analyst in early 2008, he was closeted at work, though out in other parts of his life. As a seemingly straight guy, the captain of his high school football team, TerVeer says he was treated as the ”golden boy” of the office, joining the supervisor and his family, for example, for a college football game. The adult daughter of TerVeer’s supervisor, however, was able to see past the closet door on Facebook. In an August 2009 Facebook message screen capture provided by TerVeer, she wrote, in part: ”My bestest friend ever is gay. He’s one fabulous [fashion] student in sanfran. So sorry, I just didn’t know.”

Regardless of the daughter’s disposition, TerVeer says his work situation went drastically downhill from there.

”Subsequently, each conversation he then began with me added a significant religious element,” TerVeer stated in a March 13 affidavit related to his discrimination complaint, referring to his supervisor. ”He began regularly lecturing me about his religious beliefs in an effort to force me to submit to those at the exclusion of mine. … [My supervisor] directly confronted me about my sexual preference for the first time on June 21, 2010. He came into my office on that date and said he wanted to educate me on Hell and that it was a sin to be a homosexual. He said he hoped I repented because the Bible was very clear about what God does to homosexuals.”

Four days later, TerVeer states, he and his supervisor had a dispute regarding TerVeer’s annual performance review: ”[He] became extremely upset and vehemently denied that my homosexuality and his personal views had an impact on his ratings of me. He accused me of attempting to injure his career and reputation and to ‘bring down the Library.’ I declined to sign the review and reiterated that I believed [he] was engaging in illegal discrimination and harassment of me because of his religious views regarding my homosexuality.”

At the same time, TerVeer also sought medical attention for the stress he was experiencing at work. A physician’s assistant treating him stated on a Library of Congress medical form, ”Mr. TerVeer has been suffering from worsening anxiety/panic attacks as a result of stress in [the] workplace. Attempted treatment with [anti-anxiety medication] Lorazepam, but symptoms worsened. … Currently engaged in psychotherapy.”

TerVeer says that therapy included getting a job working as doorman at a gay bar, Number Nine, at 1435 P St. NW.

”That was part of the remedy, to keep me working and to keep me social, keep me in an environment that was supportive of me, versus the hostility I faced,” he says. But the comfort of that safe haven was also breached, he adds, by being filmed while working the door by a higher-ranking supervisor. TerVeer guesses that this second supervisor may have been trying to collect evidence to show that his disability claims were meritless, adding that the two never discussed the incident.

”He never talked to me about it, and I never spoke to him,” he says. ”I didn’t know what to say. What do you say? ‘What the hell are you doing filming me here?’ Because of everything that was going on, I didn’t want anything to complicate things. I let him do what he wanted to do. While it was traumatic for me to have him come there, particularly with everything going on, I just didn’t want to have to deal with it. I had a job to do.”

While every such story may have two sides, Gayle Osterberg of the library’s public affairs office confirms that no one from the library will be speaking about TerVeer’s discrimination complaint, following a policy of not commenting on ”personnel matters.”

TerVeer, meanwhile, seems grateful for the opportunity to speak out and to pursue his complaint as far as possible.

”I’m looking to be made whole again,” he says. ”I want my career back. I’ve lost a lot. I’ve become bankrupt. My credit score is gone. I’ve been fired from a government agency. The physical and emotional toll this has taken on me – on top of the financial toll – has just been astronomical. I’ve never been in a position like this before in my life. On top of having filed a discrimination complaint against your boss, you find yourself lacking places that will take you.

”I don’t want this guy to do this to someone else. He has supervisory capacity. Should he have some other problem with another employee under him, finds out they’re gay, I don’t want him doing this to anybody else. It was bad enough I had to go through it. I’ve been to hell and back and I don’t wish this on my worst enemy. No one can prepare for the devastation. You try to pick up the pieces and move on and find out you can’t. That’s hard.”

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!