Field Goals

Wade Davis talks about life on the gridiron, after the NFL and out of the closet

It seems fair enough to say that Wade Davis has an impulsive streak.

Six years ago on Christmas Eve, stranded in a Chicago airport by a Midwestern snowstorm, Davis called up the man he’d been chatting with after meeting through an online dating site a few weeks earlier. Davis suggested he fly back to New York City so the two could have their first in-person date.

”When I walked in I was like, ‘Damn. This boy’s hot,”’ he laughs. ”And he had an accent, too. I’m like melting.”

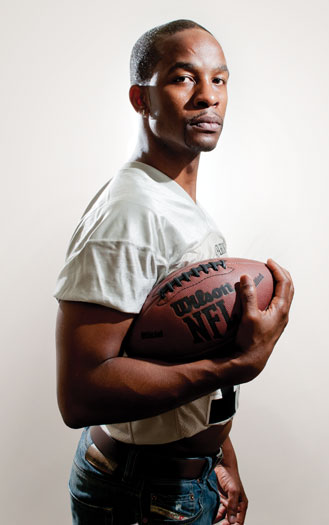

Wade Davis

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Later, sitting on the couch at a Christmas Eve party watching his date from across the room, Davis had already made his decision: ”I knew at that moment I would marry him. It was not a question in my mind, I was going to be with this guy forever. Six years later, he hasn’t gotten rid of me.”

It’s a trait that makes sense for a former professional football player, a man whose career as a free-agent cornerback in the NFL took him from the Tennessee Titans to the Seattle Seahawks to the Washington Redskins. After a lifetime of playing football – from pick-up games in the backyard to college ball at Weber State University in Utah – his left knee took him out of the game in 2004.

”I don’t have much cartilage left,” says Davis, who just turned 35, emphasizing the point with the audible grinding when flexing his knee. It was an injury that made him a risk for an NFL team, which is the end of the road for a free agent. ”When you’re a journeyman, you’re pretty much done.”

His football career may have ended, but suddenly he had the opportunity to do the one thing that he had always felt forbidden: crack open the door of his closet. After briefly moving back to Colorado – the state where he moved with his family as a teenager after being raised in Louisiana – he decided to take the leap and move to New York City.

”I just felt so free — I couldn’t wait to kiss boys, go to clubs, all of those things that I thought being gay was,” he says. But the experience didn’t match up to his expectations.

”Going to clubs, dancing with my shirt off, it wasn’t that great. People on drugs or they’re drunk and they’re just dancing around and everyone’s sweaty,” says Davis. ”I felt uncomfortable. I felt awkward. I wanted to kiss a boy, but he’s sweaty and disgusting — it was a weird phase for me.”

What ended the phase was his discovery of the New York Gay Football League. For Davis, finally, two parts of himself – football player, gay man – could coexist naturally.

”That was really the point where I felt, I can fit in here,” he says. ”There are gay guys that like sports; it created a whole new family for me.”

That set him on the journey of becoming a gay man comfortable with himself, a journey that culminated in June of this year when he came out publicly in a profile on OutSports, the gay sports website. But there’s been much more to that journey for Davis. Over the past eight years he’s focused himself on working with LGBT youth, from his day job at New York’s Hetrick-Martin Institute, to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) sports advisory board, to being part of President Obama’s LGBT outreach team. Using his own experience of both success and the closet, his goal now is to help LGBT youth of color experience much more of the former and a lot less of the latter.

Because impulsiveness isn’t the only streak Wade Davis has. There’s also determination.

METRO WEEKLY: When did you know that you wanted to be a football player?

WADE DAVIS: When I was 6 or 7, I was drawn to football on television. I would sit in front of the TV for hours and somehow I understood the game. I couldn’t explain it to anyone, but I just understood it. My neighbor’s house and ours didn’t have a fence in between, but it had a fence going around the edges, so we had probably a 30-by-80 football field in our back yard. We would play this game called ”Smear the Queer.”

MW: I’ve played that.

DAVIS: I’m pissed off at the name of that game, because the queer is actually the toughest guy — you’re willing to go pick up the ball and get tackled by 20 other guys. So why are you the queer at that point? Anyway, from that moment I started playing and I realized I was better than most of the kids out there. My mother didn’t want me to play because I was very small and skinny and frail. And my grandmother was like, ”He’s my baby! Don’t hurt my baby!”

But I just didn’t stop playing it. And because it was in my backyard, it was every week or every day. Summertimes, we’d play from 9 a.m. till the sun went down. We’d just drink water out of the water hose.

MW: Did you understand what the name of that game meant then?

DAVIS: I had no clue what that meant. I didn’t have the language to understand what ”queer” was at the time. I didn’t even really know what ”gay” meant at the time. The only term I was conscious of was the term ”bull dagger,” cause my grandfather used that referring to lesbians, or women who looked more masculine. I remember we were in the mall one day and he was like, ”Look at those nasty-ass bull daggers over there.” I was like 10 years old — you don’t even know what that means, but you start to relate certain comments to certain people.

MW: When did you start playing team football?

DAVIS: When I moved to Colorado, in seventh grade. [I learned] there’s some politics involved, even at the little-league level. I wanted to be a running back and the coach was like, ”You can’t make a pocket.” I knew it was bull — his son was a starter and I was better than his son. There was no doubt in my mind. I was stronger, I was faster, I had moves, but his son played. So I started playing cornerback and receiver. That’s when I fell in love with Deion Sanders and I decided I’m going to play cornerback forever. Deion Sanders was, for my generation, probably like what Willie Mays was to another generation. He was bigger than life. I had over 40 to 50 football cards. I had a life-size cutout. I had posters. My whole room was a shrine.

MW: When did you first have an inkling that you were gay?

DAVIS: I was in a gym-class locker room — not football, but a high school gym-class locker room. I was pretty late in understanding that. I just remember going home, watching straight porn for hours trying to focus on the woman and make myself believe that what happened was just what guys do as a comparison thing: ”Oh, I’m just comparing my body to this guy.” I think that that does happen amongst adolescent boys, but I knew at that moment it was different. Like, when I saw this guy, I wanted to hold his hand, kiss him, touch him. It wasn’t just that I wanted to have a flex off. So that was the first moment that I knew there was something different.

MW: So you go to college, you’re playing ball. How did you construct a closet?

DAVIS: I started to emulate everything that I saw straight guys do that I thought I should do. Having a girlfriend, wearing oversized pants and oversized T-shirts. Making sure that if I went to a club I took a girl home with me – whether we did anything or not, which most times we didn’t. I looked the part of a straight guy, a football player who didn’t do anything that was gay. And I was always a shit-talker. I was born to talk shit, so that came easy for me.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!