Calling on Clinton

As gay rights take center stage, some wonder why the popular former president is seemingly in the wings

By Justin Snow

January 3, 2013

There were high expectations for former President Bill Clinton when he walked out onto the blue-carpeted stage at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C., in September.

The former president had become a staunch defender of President Barack Obama, leaving behind perceived animosity developed over a long and brutal primary fight between Obama and Hillary Clinton in 2008. With Hillary Clinton serving as secretary of state and Obama in a heated race against Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, all eyes were on the great communicator Sept. 5, with supporters hoping Clinton could lend his charisma and fight to a president sometimes perceived as distant.

”We’re here to nominate a president, and I’ve got one in mind,” Clinton said to cheers from the packed Time Warner Cable Arena.

President Bill Clinton

For 50 minutes Clinton spoke about the economy in a policy-heavy speech that ran 10 minutes longer than Obama’s own speech the following night. Often veering from his prepared remarks, Clinton dissected Romney’s plan for the economy in a style that reminded many what made Clinton one of the most successful politicians of the late 20th century. Observers declared Clinton’s speech a rousing success, but for LGBT Americans there was no denying what was left unsaid.

Considered a pillar of the modern Democratic Party, two of the most lasting legacies of Bill Clinton’s presidency were anti-gay policies that have taken nearly two decades to undo, and whose undoing has been largely assisted by the president Clinton went to Charlotte to help re-elect.

Despite campaigning a year earlier on the promise that gay and lesbian Americans would at last be allowed to serve openly in the American military, Clinton and Congress approved ”Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 1993 as a compromise to the full ban on gay servicemembers that existed when Clinton entered the White House. Gay people would be allowed to serve under Clinton’s compromise, but by sharing their sexual orientation they faced discharged. And discharged they were, with more than 14,500 LGB servicemembers fired under the discriminatory ban before its repeal in 2011.

”He probably should have mentioned it,” gay retired Army Gen. Keith Kerr told Metro Weekly in a phone interview from his California home shortly after Clinton’s speech last September.

The 81-year-old Kerr, who worked for years to repeal DADT and was a member of Hillary Clinton’s 2008 campaign for president, said acknowledgment by Bill Clinton of the policy he signed into law could have sent a strong message more aligned with a party convention that highlighted Obama’s repeal of the discriminatory policy multiple times.

Although Kerr said he initially supported DADT as a compromise when it was implemented in 1993, he quickly grew wary of its misuse as it became a ”weapon of vengeance anytime someone had a gripe against a gay servicemember.”

Sue Fulton, an out gay veteran and graduate of West Point, added that Bill Clinton is probably sick of being blamed for DADT and the corner he was pushed into by congressional Republicans.

”Too many people in the gay community blame him for a policy that was in principal a decent compromise. The problem was that the policy wasn’t implemented as promised,” said Fulton. ”Perhaps he’s more culpable for DOMA than DADT, but it’s hard now to remember the political climate of that time and how much things have changed.”

Indeed, while the political climate of the 1990s has been blamed more than Clinton for the implementation of DADT, it is his signing of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act for which he has faced continued criticism.

It was shortly after midnight, Sept. 21, 1996, when Clinton signed DOMA in what was a highly expansive and intrusive federal ”power grab” that forbid federal recognition of same-sex marriages in all states.

In a statement released one day before signing DOMA into law, Clinton hinted at his qualms with the bill.

”Throughout my life I have strenuously opposed discrimination of any kind, including discrimination against gay and lesbian Americans,” Clinton said. ”I have long opposed governmental recognition of same-gender marriages and this legislation is consistent with that position.”

In the same statement, Clinton affirmed his support for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act and urged Congress to pass that legislation.

”I also want to make clear to all that the enactment of this legislation should not, despite the fierce and at times divisive rhetoric surrounding it, be understood to provide an excuse for discrimination, violence or intimidation against any person on the basis of sexual orientation,” Clinton said. ”Discrimination, violence and intimidation for that reason, as well as others, violate the principle of equal protection under the law and have no place in American society.”

It was not popular to oppose DOMA in 1996. Congress approved the bill overwhelmingly with only 14 Democrats voting against the bill in the Senate. Although the act was largely meaningless at first, that changed as the fight for marriage equality expanded. When Massachusetts became the first state to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples in 2004, those couples were denied more than 1,000 benefits enjoyed by married straight couples because of DOMA.

READ NEXT

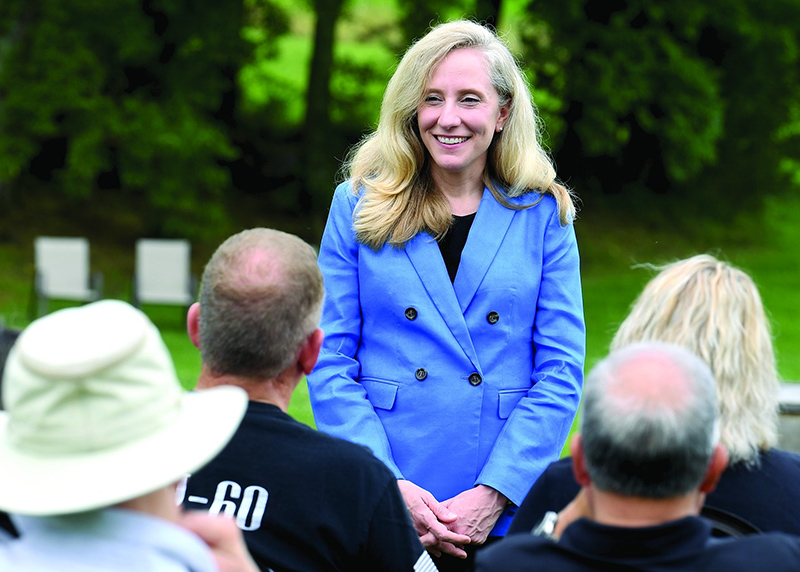

Abigail Spanberger Backed by HRC in Virginia Governor Bid

The campaign arm of the Human Rights Campaign is endorsing Democrat Abigail Spanberger, who is seeking to become Virginia's next governor.

By John Riley on April 23, 2025 @JRileyMW

The Human Rights Campaign PAC has endorsed Democrat Abigail Spanberger to be the next governor of Virginia.

The endorsement by the nation's largest LGBTQ advocacy organization comes at a time when some Democrats are urging members of their party to distance themselves from the LGBTQ community.

Spanberger, one of the more conservative members of the Democratic House Caucus during her six years in the U.S. House of Representatives, has been praised by some pundits for her criticism of left-leaning voices within the Democratic Party, especially on issues like public safety, national security, and support for Israel.\

‘A Nice Indian Boy’ Spares No Layer of Sentiment

A blandly sweet gay romance, "A Nice Indian Boy," starring Karan Soni and Jonathan Groff, looks great but lacks buoyancy.

By André Hereford on April 5, 2025 @here4andre

Like a warm hug wrapped in a warmer turtleneck, A Nice Indian Boy spares no layer of sentiment limning the love story of two nice Indian boys, Naveen and Jay.

Actually, Jay, played by Looking's Jonathan Groff, is a white American orphan who was adopted and raised by an older Indian couple.

They've since passed on, but Jay is still the nice Indian boy whom Naveen (Karan Soni) brings home to meet his traditional parents, Megha (stand-up comedian Zarna Garg) and Archit (Harish Patel), and his moody older sister, Arundhathi (Sunita Mani).

The featured meet-the-parents encounter follows a generously paced first act, in which hospital doctor Naveen and professional photographer Jay almost meet-cute praying in front of the Ganesh altar at a Hindu temple. It's practically love at first sight, a mutual epiphany of interest and attraction that Soni and Groff make both cute and credible.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

The Magazine

-

Most Popular

"Senate Twink" Says Video Sex Scandal Drove Him to Flee U.S.

"Senate Twink" Says Video Sex Scandal Drove Him to Flee U.S.  Abigail Spanberger Backed by HRC in Virginia Governor Bid

Abigail Spanberger Backed by HRC in Virginia Governor Bid  Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'

Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'  'Boop! The Musical' Is Broadway’s Happiest Surprise

'Boop! The Musical' Is Broadway’s Happiest Surprise  A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'

A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'  Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal

Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal  Lesbian Firefighter Awarded $1.75 Million in Lawsuit

Lesbian Firefighter Awarded $1.75 Million in Lawsuit  Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'

Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'  'Porn Star University' Started by Gay-for-Pay Creator Andy Lee

'Porn Star University' Started by Gay-for-Pay Creator Andy Lee  Nick Cave: The Wizard of Art

Nick Cave: The Wizard of Art

"Senate Twink" Says Video Sex Scandal Drove Him to Flee U.S.

"Senate Twink" Says Video Sex Scandal Drove Him to Flee U.S.  Abigail Spanberger Backed by HRC in Virginia Governor Bid

Abigail Spanberger Backed by HRC in Virginia Governor Bid  Lesbian Firefighter Awarded $1.75 Million in Lawsuit

Lesbian Firefighter Awarded $1.75 Million in Lawsuit  Nick Cave: The Wizard of Art

Nick Cave: The Wizard of Art  Trans Women Not Legally 'Women,' UK Supreme Court Rules

Trans Women Not Legally 'Women,' UK Supreme Court Rules  Chef’s Best Is A Culinary Extravaganza For A Cause

Chef’s Best Is A Culinary Extravaganza For A Cause  This Week's Advertisers: Nick Cave - April 17, 2025

This Week's Advertisers: Nick Cave - April 17, 2025  Off-Broadway's 'All the World’s A Stage' Is Tender, Timely, and True

Off-Broadway's 'All the World’s A Stage' Is Tender, Timely, and True  'Boop! The Musical' Is Broadway’s Happiest Surprise

'Boop! The Musical' Is Broadway’s Happiest Surprise  Naples Pride Sues City Over Drag Show Ban

Naples Pride Sues City Over Drag Show Ban

Scene

Metro Weekly

Washington's LGBTQ Magazine

P.O. Box 11559

Washington, DC 20008 (202) 638-6830

About Us pageFollow Us:

· Facebook

· Twitter

· Flipboard

· YouTube

· Instagram

· RSS News | RSS SceneArchives

Copyright ©2024 Jansi LLC.