Lightning Strikes Again

Bringing back Tracks for a special reunion weekend

Like so many others, Patrick Little credits Tracks in making him the gay man he is today. ”It’s a common story of Tracks,” he says. ”I walked in the door straight and came out gay a few years later.”

Little, a native of Fredericksburg, Va., eased into his sexuality by initially only going to D.C.’s legendary gay nightclub on Thursday nights, which was an industrial/goth/punk-themed party, more straight than gay. ”I knew there were gay nights, and that was too scary,” he says, chuckling at the memory. Eventually, though, he did muster the courage for Saturday nights. ”Once I’d gotten over the huge hurdle that was, ‘I’m going on a gay night,”’ he says, ”I realized it wasn’t only gay folks there. There were straights as well. It was less scary.”

Tracks logo

Ed Bailey, D.C.’s leading gay nightlife impresario, refers to Tracks, his very first club, as ”a game changer” in the city. ”Tracks was a social haven for gay people that also allowed you to move beyond just the sphere of the gay community,” Bailey says. ”It allowed you to be gay and social with people that weren’t just gay, but all kinds of people.”

This weekend, Little and Bailey will help commemorate the influential club with a series of parties, all part of an improbable but inspiring Tracks Reunion event that Little helped cultivate through Facebook over the past couple years. ”We started to have conversations with people, and realized that it was a viable idea to have a reunion,” says Little, who spent six years of a 12-year career at Tracks as the club’s last general manager. It became especially viable once most of the key players from the club’s 15-year reign in D.C., 1984 to 1999, signed on — most significantly founder and owner Marty Chernoff.

”I’m thrilled about this reunion,” says Chernoff, who launched Tracks D.C. a couple years after the original Tracks in his home of Denver, which is still in operation today. ”I would love to say that I’m a great social motivator,” Chernoff says, referring to his club’s socio-cultural impact, ”but it would be disingenuous. The real truth is: I saw an opportunity to have a positive business influence, and the fact that I was able to do some good work is a nice fringe benefit.”

Much of Chernoff’s good work is immeasurable. ”I am what I am today because of Tracks,” says Little, noting that the slogan ultimately applies to all of those associated with the reunion. Without Tracks, Little might not have developed the management and marketing skills he now puts to use as an Alexandria-based executive recruiter. Without Tracks, Bailey, who’s a club DJ as well as a promoter, might not have fallen so hard and so completely for the club world. He might have opted to pursue a career in linguistics instead, putting to use his master’s degree from Georgetown.

Without Tracks, in other words, D.C.’s gay nightlife scene would likely have been significantly smaller. There’d be no Town Danceboutique or Number Nine, to name two of Bailey’s current ventures with longtime business partner John Guggenmos. Guggenmos was part of the team that revived Tracks in the first half of the 1990s through stronger promotion and beefed-up security. ”Had it not been successful, I probably would be done, back in Colorado or Wyoming with therapy clients,” admits Guggenmos, a Wyoming native who earned a master’s in counseling from George Washington University.

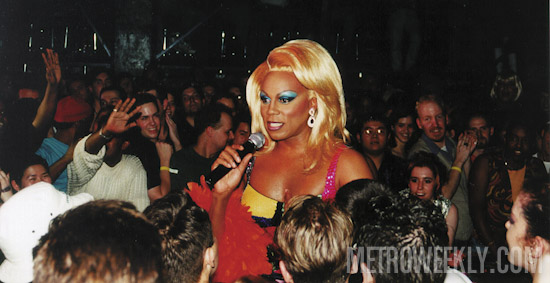

Everybody say love! RuPaul at Tracks — Click for more photos

But Guggenmos adds that it was the patrons — the club kids — who really made Tracks extra-special. ”They’re the ones that created the energy and the dynamic,” he says.

”Tracks was special because you got to meet so many different people from so many different walks of life,” Little adds. ”It was kind of an island of misfit toys, I guess you could say, but I mean that in an endearing way…. Tracks was a really safe place to go. It was without judgment. It embraced people’s uniqueness.”

Of course, it wasn’t necessarily safe getting there. ”Back then gay bars were in the ghetto,” he notes. Tracks stood a few blocks from where Nationals stadium is today. ”Back then, it was a lot of public housing, and the neighborhood certainly wasn’t developed as lovely as it is now.”

But there was just something about that place, and that time. ”People hold Tracks so dear to their heart,” Little says. ”It’s been really humbling to know that I was part of something that was so transformational, whether it be from a social standpoint, or the music.”

Bailey, who DJ’ed Saturday nights and was in charge of promotions every night at Tracks in the early ’90s, couldn’t agree more and we sat down with him to get a fuller look at the club that forever changed the nightlife of Washington.

Read more about Tracks Reunion Weekend:

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!