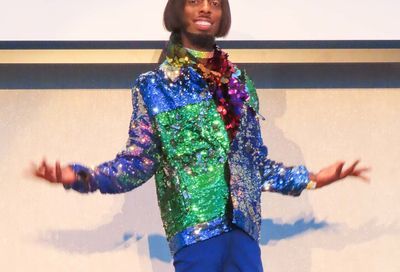

Interview: SMYAL’s Sultan Shakir

SMYAL's newest executive director took the reins of the organization in August. Now he hopes to build and expand upon its mission to build youth leaders.

Sultan Shakir had once planned to be a musician, even going to the Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University to major in double bass performance. But a funny thing happened on the way to the stage: Shakir got bitten by the activist bug.

“I actually decided at that time in my life that I could continue with the path I was on, which was to become a performing artist,” says the former community organizer who cut his teeth fighting predatory lending practices in downtrodden neighborhoods in West Baltimore, “or I could use my youth to help change the world, and help change some of the power structures that are in place and are intentionally keeping people oppressed.”

Throwing himself into campaigns to create change, Shakir went to work for the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) as a field director, focusing on various political fights aimed at advancing LGBT rights. He eventually rose to the position of campaign manager, overseeing the fight to pass marriage equality legislatively, both in the District and in Maryland. After those victories, he began working as HRC’s youth and campus engagement program director, providing the perfect springboard to his current job as executive director of Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders (SMYAL), after former executive director Andrew Barnett announced he would be stepping down last summer.

For Shakir, social justice and fighting oppression — in whatever form it takes — has always been important. In that way, SMYAL’s mission, which is to provide support and resources to LGBT youth and encourage them to take on leadership roles in advancing causes they believe in, dovetails nicely with his professional background. But Shakir isn’t content to rest on SMYAL’s past successes, saying he feels the organization’s programs are “ripe” for expansion. That expansion comes with a price tag — Shakir will have to ensure SMYAL gets its fair share of government grants, as well as seek financial support from corporations, private foundations, and individual donors by convincing them that the organization is a worthy cause in which to invest their money.

“Part of the challenge that any executive director faces is identifying what the organization has the capacity and resources to do, and what the organization does well,” Shakir says. “So is there more work we could do? Absolutely. Until we stop hearing about LGBTQ youth struggling in school or with their sense of identity, or needing more resources, there is a need for SMYAL.”

METRO WEEKLY: Tell us about your childhood.

SULTAN SHAKIR: I was born and raised in North Philadelphia, in a household that I would call religious — and I want to clarify that because I think that, like a lot of other households, it was sometimes religious and sometimes not. Specifically, we were raised Muslim. The interesting thing about that is my parents came through the Black Power movement, and the Nation of Islam, so it was partially about God and religion, but also partly about race and society, and how society saw black people, and how religion — particularly Islam — could help strengthen the black family that was destroyed through slavery and the institutions after slavery.

And so, in my childhood, from both the religious and cultural sides, I remember feeling a sense of disapproval — a sense that I was failing to do what the religion expected of me as a strong black man, because I was gay in a male-dominated society that didn’t see being gay as a strength. I see a lot of youth, nowadays, who are in similar spaces, where even if you’re not in the religion, you still feel its pull and the message from those who claim to speak for the religion that being gay makes you ‘not enough,’ that being gay, or lesbian, or bisexual, or transgender, is not okay.

Even when I was working at the Human Rights Campaign in a similar role, we had a program where we would work with youth who were the same age as some of the youth at SMYAL, and a lot of it was about identity development. And at one point in a retreat we did every year, we would ask the youth to stand in a circle. And we would mention different scenarios or comments, and if you agreed with the comment, you would step into the circle; if you didn’t, you would stay where you were. And one of the comments was that being gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender was a sin. And over half the youth would step inside the circle. We really had to spend a lot of time unpacking that, because a lot of the work we were doing, as we do at SMYAL, was about developing youth leaders. From my own experience, I know that, unless you can really be comfortable as your complete self, it’s challenging to stand out in front of anything and lead.

So, I went to college in Baltimore, and that was where I think I had my first really transformative moment, in terms of my relationship with people in power. I was doing community organizing in West Baltimore, and I was working with low-income residents, many of whom were struggling with predatory lending at a time when it wasn’t really on the national radar. We had one member who was in a loan, she had a “balloon payment,” where she would pay a little bit each year, and at the end of the loan she would be forced to pay a large amount. And the mortgage company knew she wasn’t going to be able to pay that, and so they took her home. One of our members became a member of the community organization and helped us do that kind of education and organizing work. He actually had a job where he said it was clear that his main role was to put people in loans they couldn’t afford, so the mortgage company could take the house back and sell it to somebody else. Banks understood that they were ripping people off, and understood that they were in a largely unregulated market that nobody was paying attention to, because it was a market that was only affecting poor black people.

MW: What did you do after college?

SHAKIR: After college, I started working for a consulting firm called Grassroots Solutions. We got to do some really great work with different nonprofits. We worked with Planned Parenthood to help tell young unmarried women that the decision in that presidential election would have a huge impact on a woman’s right to choose. Particularly young women, who were also unlikely to vote.

From there, I went to work at the Human Rights Campaign, where, for seven years, I worked in the field department, running grassroots campaigns. I was the campaign manager for the D.C. marriage campaign and the Maryland marriage campaign. One of the first campaigns I did for HRC was called “Four Days for Equality,” when we were working with groups in Pennsylvania to bring LGBT people to Pennsylvania to knock on doors and to work in coalition with other organizations to defeat Rick Santorum. I got to do some great work that really impacted people’s lives, everything from passing marriage equality in Maryland, even when national groups said it wasn’t possible, to stopping a sexual orientation and gender identity-inclusive nondiscrimination bill from being repealed on the ballot in a small town in Florida.

After that, I worked at HRC as the director of campus engagement, and that’s when I started to focus my work on building the next generation of leaders, and working on unpacking what it is that young people need to recognize their own potential, and how we, as a community, can support young people in addressing the challenges they face. And then from there, the work naturally transitioned over to SMYAL, which is what SMYAL does on a day-to-day basis. It’s a strong, solid organization, where we are working with young people who have the potential to be leaders, and our job is to empower that.

MW: When did you first come out to your parents?

SHAKIR: In college, and that was a decision that was largely based on my faith. And I say that because what I was told from my faith at the time was that being gay was wrong. I also knew that lying was wrong. I knew I was gay, I knew it wasn’t a choice, I knew it was something I couldn’t change, and the only thing I could do was not lie about it. I’ll never forget sitting behind the cafeteria at school and just crying, because I could finally resolve in myself was that the only thing I could do was be honest about the fact that I was gay. I said to myself, “If anybody from here on out asks me if I’m gay, I will tell the truth about it.”

A couple of weeks after that, I went home from school, and my boyfriend called me from Baltimore, because he had a pair of capri pants, and the hem had come out. And this was before guys were wearing capri pants, and I said, “All right, don’t worry. Come up to Philadelphia, I’m sure we can find a pair.” And I get ready to go meet my boyfriend at the mall, and my dad — who was a big guy, a disciplinarian at school — comes to the top of the steps and says, “I was listening in on that phone call. Is that guy gay?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Are you gay?” And if this had been two months prior, I would have said no. But I said, “Yes, I am.” And he said “Okay.” And from there, he wanted to meet my boyfriend, and I said okay. It was rough.

I can’t speak for my dad. I have my own interpretation of my dad’s process of finding out his son was gay. I do know that it was very difficult for him, very difficult for my mother, who said, “You’re my son, but you’re sick.” And it was difficult for the family. My grandmother was always 100 percent supportive.

My family, now, is great — after they’ve had time to talk about it, time to process it. My dad even came to the Supreme Court rally when they were hearing the marriage case. He comes to my rowing meets, and hangs out with the other members of the gay rowing club. So, today, we’re in a much different place, but at the time, it was a very hard moment in the family history.

MW: Did they try to get you into reparative therapy or any religious group, or tell you not to act on it?

SHAKIR: No, they did not try to put me into reparative therapy. They were concerned about me going back to school because they thought I was being influenced by gay people in the school. And so they asked me to promise that if they sent me back to school, that I would never talk to another gay person again. So I made that promise, drove back to school, and that’s the last we really talked about it for a while. It was also really hard on my relationship with my boyfriend. We actually ended up breaking up, because I wasn’t emotionally able to process everything that happened with my family, and still emotionally support another person.

It also created a really big rift between my dad and me. My parents were divorced before I went to college, and I spent a lot of time with my dad. And not being unconditionally loved by him really hurt. So I stopped answering his phone calls, I would stop answering when other family members called, and I really retreated, because I wasn’t sure how to live a life with my family, and also live a life with a potential partner.

It wasn’t until sometime after college that I would say I forgave my dad about what had happened. And he said he wanted to see me, I went down to visit him in Florida that Christmas. And we didn’t talk a lot about it then, but we’ve talked about it much more since then. I mean, he’s asked about boyfriends, he’s been over to the house. This one day, we were sitting on the couch with my stepmom, my roommates are there — we’re all gay — and I’m flipping through the DVR, and I know that RuPaul’s Drag Race is going to come up, so I start flipping through very quickly, and he says, “Oh is that RuPaul’s Drag Race?” And I say, “Yes, it is.” And he says, “I love that show!” [Laughs.] So we sat there and watched about three hours of RuPaul’s Drag Race, which was huge, and a moment that, when I was first coming out, I never would have imagined happening years later.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.