The Legacy of Michael Kahn: An Interview with the D.C. Theater Legend

All's well that ends well for the departing artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company

“Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

The line, one of William Shakespeare’s most famous, hails from Twelfth Night, one of the bard’s most popular comedies. Though the Shakespeare Theatre Company has produced the play numerous times, it was directed only once by Michael Kahn, in 1989, three years into the artistic director’s three-decade tenure.

To say the phrase can be applied to Kahn is something of an understatement. One could argue Kahn, departing the Shakespeare after 33-years, was born to be one of the world’s greatest directors of stage (and opera), and that, upon taking the helm of The Folger Theatre in 1986, achieved for the intimate Capitol Hill-based theater a surge of greatness that brought it the kind of international prestige most regional theaters only dream of.

As for having greatness thrust upon him, that would come in the form of all the actors, designers, collaborators, and dreamers handpicked by Kahn to bring their own talents to light in each new production, adventure, or risk the company undertook. Shakespeare has always been relevant, of course. But Michael Kahn took it to new levels in Washington, D.C.

When Kahn — who had already served as artistic director at the American Shakespeare Company in Stratford, Connecticut and the McCarter Theater in Princeton, New Jersey — first arrived in D.C., The Folger was on its last gasp, having been defunded by the National Endowment for the Arts. Within his first three years, Kahn had turned things around. By 1990, his seasons had become so popular, there weren’t enough seats to accommodate audience demand. The company ultimately left the Folger (which, under the watch of Janet Alexander Griffin has had its own separate, brilliant, award-winning run that continues to this day) for the Lansburgh Theatre.

If over the past 33 years you’ve been fortunate enough to see one of Kahn’s sixty-odd productions at The Shakespeare, then you are abundantly aware of the meticulous care he brings to everything — from Shakespeare to Molière, from Pinter to Williams. That doesn’t mean every production is an out-of-the-park hit, or even a solid work of art, but there is a certain high level of quality associated with him that rises above all others. Every Kahn-helmed production exhibits the effort, creative muscle, careful thought, and, most of all, joy for creating theater that he and his collaborators put into their work.

“Michael doesn’t give an actor a character to play,” says Ted van Griethuysen, an actor who Kahn convinced to join the resident company in the mid-80s and who became a Washington star in his own right. “He figures that’s your job, that’s why he’s hired you. He can be demanding, he can occasionally be difficult, but very rarely. Michael expects a lot. He’s very smart, and in some ways I feel Michael’s been punished by being very smart. He’s a taskmaster, but he’s the taskmaster on behalf of your very best. One of the things I realized with Michael was that he really can’t stand watching an actor doing less than what that actor is capable of doing.”

The 84-year-old van Griethuysen credits Kahn with giving him a second life.

“When I arrived in Washington, I was 52,” says van Griethuysen. “You would think that by that time, the high point of a career had likely been passed, but I can’t say it was. In a fashion, at that point in my life, I was ready to do a lot of work of one kind and another, and Michael gave me the opportunity to do the parts that I wanted to do. He gave me parts I’d never dreamt of doing. I’m not sure that I would have reached my present age of 84 in fairly good health had it not been for the work that Michael provided me in those 30-some-odd years.”

He concludes, “A lot of actors will tell you that acting and life are pretty much the same thing for us, and in a fashion, Michael gave me life and opportunities to express what I had seen and learned as a human being about myself, about life, about the arts, about Shakespeare. He gave me room to breathe.”

Kahn is leaving the company he built in what he feels are good hands — Simon Godwin, the 40-year-old Associate Director of London’s National Theatre. “He’s very smart,” Kahn says of Godwin, who recently revealed his first full season for The Shakespeare. “He’s very energetic and committed to work. He’s got a wonderful personality that is very engaging and quick. He’s got tremendously interesting experience as a director. And he cares deeply about Shakespeare. The staff is already rather enchanted by him. He’s got that kind of personality. I think he was absolutely, absolutely the right person of the candidates. I think the board made a correct decision.”

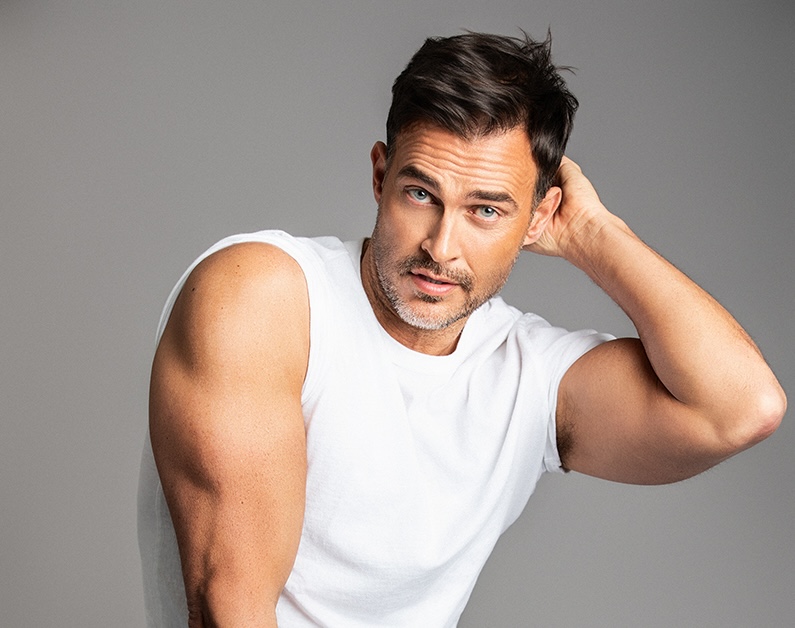

Kahn — who graciously took time from a demanding rehearsal schedule for his epic final show, Ellen McLaughlin’s adaptation of Aeschylus’ The Oresteia, to sit for a cover interview (his fourth with Metro Weekly) — seems at ease with his decision to leave, though at the time of the announcement a few years back, the news hit the local theater community with a palpable sadness. In the ’80s, Kahn, along with Joy Zinoman and Howard Shalwitz, former heads of The Studio and Woolly Mammoth, and the late Arena Stage founder Zelda Fichandler, laid the foundation for a thriving Washington, D.C theatrical community that, creatively and collaboratively, is unmatched in any other American city, save, perhaps, New York.

The Brooklyn-born Kahn, who came out publicly early in his tenure at The Shakespeare, has been an advocate for LGBTQ causes (he even served as a judge for this magazine’s Next Generation Awards). He’s had two significant, long-term relationships, the first ending tragically when his longtime partner Frank Donnelly died of natural causes two days after the events of Sept. 11. Several years ago, Kahn began dating again, settling down with Charles Mitchem. The pair were married on May 17, 2015, by Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

“I still think about it,” says Kahn of that day. “It was a really wonderful experience.” For his part, he’s looking forward to wrapping things up at the Shakespeare Theatre and settling permanently in New York City. “I’m looking forward to moving back to New York and living with Charles,” he says.

The rest of us will undoubtedly feel the loss, particularly the artistic contributions he made to this community — although you’ll get one more look at his magnificent Hamlet, starring Michael Urie in a brilliant take on the character, which is making a return as this summer’s Free-for-All.

For 33 years, Michael Kahn called Washington his creative home. And, in the process, he forged a remarkable, lasting legacy that our city can be forever grateful for.

METRO WEEKLY: Do you remember the first day you took the reins at the Folger Theatre?

MICHAEL KAHN: Yes. I remember a lot of things about the first day that I got here. The night I got here — at that time, it was with my [late] partner Frank. We were put into an apartment on East Capitol Street. It was a three-floor walk-up. I didn’t even know where I was in Washington. I’d only come to Washington to go to the Kennedy Center, so I actually thought that was Washington. I went up the stairs, and for some reason in the middle of the night, I had chest pains. I’m not a hypochondriac, but I said to Frank, “Something’s wrong.”

He said, “We’d better go down and find a taxi.” It was like one o’clock in the morning. And so a taxi came by and I said, “I need to go to the hospital.” I got in, and then he drove about four blocks, and stopped for another passenger. I finally got into the emergency room and a very nice doctor examined me and said he didn’t see anything wrong. He asked if there was anything happening in my life that might cause anxiety. I said, “Well, actually, I’m the new artistic director at the Folger Theatre,” and he said, “That’s it. That’s it.”

The next day, I walked into the Folger office, which I’d never been to before — it was in a little building on the corner of Third and East Capitol. Everything was in it — the costume shop, everything. It was a former undertaking establishment. Pinned to the bulletin board was a letter from an artistic director of a theater in Washington commiserating with the staff that this “carpetbagger” had arrived.

MW: The carpetbagger being you.

KAHN: Yeah. I don’t know who put that up there. I mean, I ended up liking that staff enormously, and vice versa. But that was the first day. So those were ill omens, but I was excited about doing it. That evening, I went to a little restaurant on Massachusetts Avenue and I was eating dinner with the managing director at the time, MaryAnn de Barbieri, who I became very fond of, and Teddy Kennedy walked in. I thought, “I’m in Washington.” I got all that patriotic fever.

Then, on the opening night of Romeo and Juliet, our first show, I walked to the theater and sunset was coming over the Capitol, and it was so beautiful, it was so Washington. I just knew at that moment I was glad to be here.

MW: What prompted you to take the job here?

KAHN: It was all a surprise. I had stopped being an artistic director — I’d left McCarter, I’d left Stratford, and I was teaching. I thought I was done with Shakespeare when I left Stratford after ten years, and I thought I didn’t have anything more to give to this extraordinary playwright. And so I didn’t think I should do that anymore. And then I left McCarter. I didn’t want to do budgets and deficits. So I started teaching at Juilliard and Circle in the Square and at NYU. I was teaching in all three schools. The joke was that if you didn’t want to study with me, you had to go to Chicago. But I liked it because every restaurant I ever went to I got free drinks, because the waitstaff were always people who were my students in one way or another.

Anyway, I was called down here to talk to the board of the Folger when they were going to close the theater to discuss what a classical theater should be. I don’t know how many months later I got a call asking if I was interested in being the new artistic director. I had known the theater was having a lot of trouble.

MW: It was on the precipice of shutting down.

KAHN: It was gonna close, and I’d been on the NEA panel that had, quite frankly, defunded the theater for artistic reasons. I had an idea that maybe working in Shakespeare again after all that time, and working in an intimate theater would be something that I would love — I used to work in very big theaters. So I said, “Yes.” I thought I would be here for two or three years. I mean, I had a life in New York: I had a partner, I had a job at Juilliard, an apartment — which is still where my current husband and I live in now — and I thought I would be here for a few years just to see if we could make it work.

MW: That turned into 33 years.

KAHN: Well, what happened was when I had an idea, we did it, and every time we had a plan, we did it. One by one. The Free Shakespeare. The school. I mean, things just kept happening, and the audiences came. So there was no reason to leave. All these projects were exciting. There was always something ahead that we were planning to do.

MW: I still remember your first production — Romeo and Juliet. I was a theater critic at that time, and it was a revelation. We had simply not seen Shakespeare like that at the Folger under your predecessor. I especially remember Pat Carroll as the Nurse.

KAHN: That was her first Shakespeare.

MW: That’s one thing that you did for this town that no one had really achieved — to bring well-known names from either New York stage or film and television into our intimate environs. You brought in Pat Carroll. Over time, you brought in Avery Brooks, Andre Braugher, Tom Hulce, Patrick Stewart, Dixie Carter, Stacy Keach. But the people in your resident company — Ed Gero, Floyd King, Fran Dorn, Ted van Griethuysen — you made them stars in their own right.

KAHN: They are stars. And people miss them when they’re not in shows now. They’ve all scattered to the wind. But no, I just went about doing things that I’ve been doing all my life. Our budgets at The Folger were very small, but there were people who were well-known who wanted to do this material, who had trained for it, who had the ability to do it. Pat Carroll had never done Shakespeare, but she had this incredible ability to do language. I just thought she’d be amazing. It was a great success for her, and she played loads of parts for us.

Stacy, I had known in New York as one of the best Shakespearean actors in America, and so I was very grateful when he said he wanted to do Richard III. That was at the Folger, which was a 274-seat house, so the fact that he would come and do that — and he didn’t get any more money than Floyd King was getting. It was the same salary — they weren’t coming for that, they came because they wanted to do that material. And so when Dixie Carter came, or Kelly McGillis came, the people that were recognizable, they had the skills to do it. Kelly had studied four years at Juilliard. You didn’t like her, I remember.

MW: You never fail to bring that up.

KAHN: [Laughs.] That’s okay. Well, listen, you were not alone. You were not alone.

MW: I liked Dixie!

KAHN: Well, Dixie was wonderful. No, I just was thinking that you were not alone in not liking Kelly. Lots of other people didn’t like Kelly. I created a whole season for her that she then couldn’t do because then she got pregnant, if you remember.

MW: Let me ask you a question about the Folger, specifically, because it’s a replica of an Elizabethan stage. Was there a certain magic to being in that space, surrounded by the library with its folios and the historic documents?

KAHN: I didn’t have romanticism about it. What I liked about it was how small it was for me to be able to work intimately with an audience and actors. I’d never had that opportunity with Shakespeare, where you could see the faces and the eyes. But to be honest, I went down and looked at the folios maybe once.

MW: You moved the company to The Lansburgh in 1991.

KAHN: We left because our shows were selling out. The board that brought me down to save the theater space realized that it was the company that what was important, not the space. Luckily we looked around and the Lansburgh was being built, so we moved. That was still an intimate theater, about 400 and some odd seats, so it didn’t really change the aesthetic. But it did allow for a different kind of production. Then [in 2007] we opened the Harman — it’s bigger by another 400 seats.

MW: Until I started seeing your productions of Shakespeare, I didn’t realize how much I was missing. I started to understand the work more fully through the plays you personally directed. You have this connection to Shakespeare, I think, that so many others do not.

KAHN: I’m very pleased when people say my productions have been very clear. That’s my goal and I work very hard to make that happen. I had done a lot of Shakespeare before I got here. I think I count every word that’s said in Shakespeare as being there for a specific purpose. It’s not just because Shakespeare’s writing. He chose every word at a particular place because of some intention. And so my investigation with the actors has always been, “Why do you say that? What do you mean? Why are you using those words, and what is the intention at this moment? What has just happened before this that makes that happen?” And I work that way through the whole play.

So no actor is just saying the words because it’s on the page, or they’ve learned it, or they sort of think they know what it’s about. They say it because their character has to say this at that moment — and not with other words, but those words. That leaves a lot of choices for an actor, so that one performance will not be the same as any other.

That’s why you need a lot of rehearsal. When I first got here, I knew that people hadn’t particularly liked the last few years of Folger productions, but I didn’t know what the problem was until I got here and I saw that because of budget reasons they cut rehearsal down to something like three weeks. You can’t do that. I mean, you can’t honor or investigate this writer in a three-week rehearsal. You just cannot. You have to then skip over a lot of things, and the more that you skip over things, the more incomprehensible what’s on stage is. I’ve always said I think they’re speaking English. We all understand English, but if you don’t understand it, it’s our fault, not yours. We are not finding a way to enliven these situations or these words that you can follow us.

MW: How do you think your actors would describe you as a director, in general?

KAHN: I think a lot of different things. Some say I let them explore, and that I’m a very good editor of what they do, that I don’t tell them what to do right away — and I don’t. I usually say, “Let me see what you think,” and then I edit it. There are other actors who would say I don’t give them enough chance to explore.

I really like to work with smart actors. I don’t mean intellectual actors, but smart actors who have a point of view. They’ll do something that gives me an idea, and then I throw it out, and then they take it and they do something. It’s a collaboration.

MW: I’ve heard rumors over the years that you can be pretty hard on actors.

KAHN: Sometimes I’m sharp. Actors who don’t do their work make me a little annoyed. Yet, if you’re a strong director with a lot of ideas, you can also shut actors off right away because they think, “Well, he knows everything, and he’s not gonna like anything I do, so I won’t do it.” You have to be careful about that, but sometimes I’m sharp and annoyed. I mostly like actors a lot, but I’m less patient now with actors who don’t do their homework, or are kind of lazy. I don’t know many of those.

MW: Are there any actors in particular from the old days of having a company that you really loved working with?

KAHN: I think Ed, Floyd, Ted, Fran, and Philip Goodwin were a gift to have. And then Wally [Acton] joining us. They were all gifts, to be able to have a small company who got to know each other, and we could try stuff and do complicated plays. It’s amazing to work with Fran and Helen Carey again in The Oresteia.

There were so many people I really enjoyed working with, I don’t have favorites. I would have loved to have been able to bring more actors who I’d worked with over the years into The Oresteia, but the parts required certain things. At one point, I thought maybe my last show would have everybody in it, and I would do something like You Can’t Take It With You or something like that where everybody would be in it. But it worked out for me to do this production of The Oresteia.

MW: One thing I wanted to hit on is your aesthetic. You’re a gay man. You were always out, as far back as I can remember.

KAHN: No, I outed myself in The Washington Post. I did it in an interview with Megan Rosenfeld. I’d never not been out, but not publicly. And then Post was doing this big article — it was maybe two years in or something. We were talking, and I said, “Well, you know, one of the things I think is really strange here in Washington is that I’m invited as a single man to dinners.” I said, “I’m reasonably good-looking. Why do people assume I’m by myself?”

She said, “What do you mean?” I said, “Well, I’m always invited as an extra man.” I said, “Why do people think I am an extra man?” She said, “What?” I said, “Well, because I have a partner. I’ve had a partner for 15 years.” She said, “Really? Who?” And we talked, and so she said, “Do you want that in the paper?” I said, “Yeah, I think I do.” So she put it in the article, and I was very glad she did.

A wonderful woman who was a big social leader in Washington I knew, wrote me a note telling me how proud she was of me doing that. It didn’t strike me at the time as being much of anything, but then I was getting awards from GLAAD and everything for having done this. I don’t know why it was such a big thing, that I was being asked to speak here and there, and do stuff like that. I never thought I was a gay representative, I just thought I was somebody who’d been gay since they were 16 or 17. But I was very glad I did that, and then, eventually, I thought that was one of the things I was pleased to have done. And then I was very happy to get married here in Washington in 2015 to Charles. We had Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg marry us. Those are all mighty good things.

MW: There are certain productions you directed that in my memory are —

KAHN: Are gay?

MW: Yes, well, they had a gay aesthetic, or a leather aesthetic, or something. You would take some aspect of a show into some gay territory — it didn’t overshadow things, but it was incorporated into it.

KAHN: I don’t think I do that purposely, because I think I’m trying to create whatever world I feel the play is like. But I’ve had criticism. People have said, “I’m so tired of your gay plays.” And I say back, “Well, I don’t do gay plays.”

I think whatever your own passions are come into plays no matter what. I mean, I hope that I have been able to portray heterosexual relationships as fully as I think I can. But I suppose whatever lifestyle you have — and I hate to call it a lifestyle — it has to come into the way you work. I mean, it just does. I don’t think I “gay up” plays, though if I did, I suppose I wouldn’t mind. But I have a certain kind of wit, I have a certain kind of attraction. I mean, all of those things probably come in. I’ve never been part of the leather scene, but I guess if I put that into a play, I would find that interesting. I wonder about that, because what is a gay sensibility? Well, you see certain things a certain way. You see characters a certain way, and it comes out.

In my early years, I did a production of All’s Well That Ends Well, and there was a scene in the barracks, and so I thought, “Well, why don’t they take a shower?” People are still talking about the fact the boys were taking a shower onstage at the Folger. Tom Story says it was one of the great moments of his life. I thought, “Well, maybe I did that because I think men are attractive.” But also I thought, “Well, they could be eating, or they could be taking a shower,” and I just chose taking a shower. I guess that’s gay, but that’s also what guys do in the Army, so it seemed like fun to me.

I’m also very careful. When I was doing Richard II, who probably was a gay king, I wanted it to be about an irresponsible ruler, I didn’t want it to be about a ruler who was irresponsible because he was gay. I didn’t want to feed gay prejudice by stressing that, so I worked against that. Because I thought, “I’m not interested right now, in the middle of all the arguments about equality, of showing a gay person being irresponsible.”

I think gay people are as irresponsible as straight people. I mean, being gay doesn’t mean you have to like everybody who’s gay. But I didn’t want to let people use that as an argument, so I chose not to do it that way. And yet, I thought it was perfect in Love’s Labor’s Lost, for the character Boyet that Floyd did, to make him very particularly a sort of gay socialite walker. Why was this man running around with five women all the time, and talking to them? Well, it seemed to me a very gay kind of thing to do. And Floyd said, “Gee, I hope I’m not playing it gay.” I said, “Oh, no, Floyd, you’re not. That’s what it should be.”

MW: I think it’s interesting you’re ending with a Greek tragedy. Why did you choose to close out your career here with The Oresteia?

KAHN: I’ve thought about doing The Oresteia since I was in college. It’s always stuck with me. Of course, I did Mourning Becomes Electra, so in a way I sort of did it. But this wonderful thing happened, where an actor who had worked with us came into a lot of money. He came to me and said, “Is there something you’ve dreamt about, that you couldn’t do because of resources and money?” So I immediately said The Oresteia and he said, “Well, then, I’ll support that.” And he supported it very generously. So all of a sudden I’m doing The Oresteia.

I don’t like to think of it as my final play, just another play in a long history of plays I’ve been doing. And so it would have come up, it just happens to be at the end of it. There’s something about The Oresteia, about revenge and violence and the end of all of that, that I’m interested in, that I think the world needs to hear about. We live in a world of revenge and recrimination and retribution, and we live in it whether we live in Europe and the Middle East where it’s actually people killing each other, or whether it’s just polarity in our discourse now where you say something, then I kill you, and you kill me back — which is what our current President has encouraged us to do. So that’s what I think this play is about, the end of all that. So I thought it would be a good play to do.

MW: And that just happens to be the last one.

KAHN: It happened to be the last one, yeah. I had thought about leaving the company years ago, and the board suggested I stay a little longer. I’m glad I did, because I got to do the Hamlet that I cared about a lot.

MW: The one starring Michael Urie. I loved that Hamlet. One of the best I’ve ever seen.

KAHN: I was so proud of it, and also loved working on it, so I wouldn’t have minded leaving with that show.

MW: Are you done with directing after this show?

KAHN: I don’t know whether I want to direct anything anymore. I’ve pretty much been so lucky in my life to direct everything I ever, ever, ever wanted to do. If some play hit me, that I thought, “This has to be said, and I’m the right person to help say it,” I would do it. But just to do a play now, I wouldn’t do that anymore. I’ve directed about 175, 180 productions in my life.

MW: Time to get personal. I’ve interviewed you countless times over the years and you’ve never told me your age. Will you answer that question now?

KAHN: [Laughs.] No. I think most people know how old I am.

MW: Everyone says in gay life it’s over after you’re 30. There’s no romance.

KAHN: No, but certain things are over after you’re 30, and you should just not have those things. I mean, but you can find somebody that you are in love with, and that you enjoy being with, and that you have a sexual relationship with. But it’s different. I mean, I met Charles through somebody who introduced us, because they thought I should not be by myself. It took a long time for us to come to some real feeling that we wanted to be together, and there were all the attending problems of that. Eight years later, we kind of know we’re together.

MW: Is there still romance?

KAHN: I don’t know what romance means. I mean, I love him and he loves me, and we hold hands in the movie theater and things like that. But there are days that we’re doing the laundry.

MW: So much has happened in the LGBTQ community since you first came to Washington 33 years ago. You are a prominent gay figure in our culture, in our city. What changes have you seen?

KAHN: I never had felt prejudice or anything when I went to a performing arts high school. For a little while there I was the only straight person in my class, you know what I mean? So I never personally felt the kind of oppression that so many people have felt. But to have seen it become accepted — I mean, the theater is one of the most accepting places in the world of gay people, and so many people who are gay are in charge of theaters. Agents, directors. But to see the flowering of gay rights, and to see the incredible progress that was made, like to watch now — you thought maybe for the next 10 years what we were doing would be being taken further, that we’d fight more and more for all other kinds of oppression. But to realize that now for the next ten or twenty years, we have to fight to keep what we have? That I didn’t think was gonna happen. Probably nobody thought that was gonna happen.

I was very worried about the religious right ten years ago. I said to a friend of mine, “I’m sorry, they’re the enemy, and they’re gonna be very powerful.” But I don’t think we ever thought we would see rights being taken away. I thought we would be really dealing with other issues.

I’m not a spokesman for the gay community at all. I just live my life as a gay person and it’s never been a problem, and if it’s been a problem I’ve never known. Maybe people secretly denied me work because I was gay or something, but I’ve never known about that. What I know now as a fact is that people are trying to take away the things that we all worked very hard to have, and that’s a fight now that has to be done, and has to be done all the time now. And it’s too bad. For me, that’s one of the tragedies of Trump.

MW: Do you think that, in this day of Trump, the lessons of Shakespeare are relevant? And if so, to what end?

KAHN: Shakespeare’s understanding of power and politics and what people do to get elected and what people lie about to stay in power. It’s all about that. All you have to do is look at Richard III.

MW: Does Shakespeare show us how to correct the situation?

KAHN: I think what Shakespeare shows us is that this is not the way we want to go, which is basically assassination. We don’t really want to do that. If there were ballot boxes in his time, he probably would have written a play about that. What he does show us, though, is that the voice of the people is important. He didn’t imagine that there would be such a thing as democracy. And we have to remember that we have to protect democracy, as flawed as it is.

MW: Do you think you would join the fight?

KAHN: That’s what I think I’d like to do. But I don’t know how to do it.

MW: Maybe someone will read this and reach out to you.

KAHN: Well, that would be fine, that’d be fine. [Laughs.] But I’d like to do more than lick envelopes.

The Oresteia runs from April 30 to June 2 in Sidney Harman Hall, 610 F St. NW. For tickets, call 202-547-1122 or visit www.shakespearetheatre.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.