BYU’s Matt Easton is out, proud, and heading to Capital Pride

When Matt Easton came out during his speech at "LGBTQ-unfriendly" BYU, he became a catalyst for change

When Matt Easton got the call telling him he’d been chosen as one of this year’s Capital Pride Parade Grand Marshals, he was flooded with emotion.

“I’ll be honest, I started crying,” says the recent graduate of Brigham Young University. “I couldn’t believe it. I looked at the list of Grand Marshals that had come before, and there were all these inspiring people who I’ve looked at and who I have drawn strength and courage from. So to be considered among them — I was blown away. I’m just super-humbled. Humbled and honored and excited.”

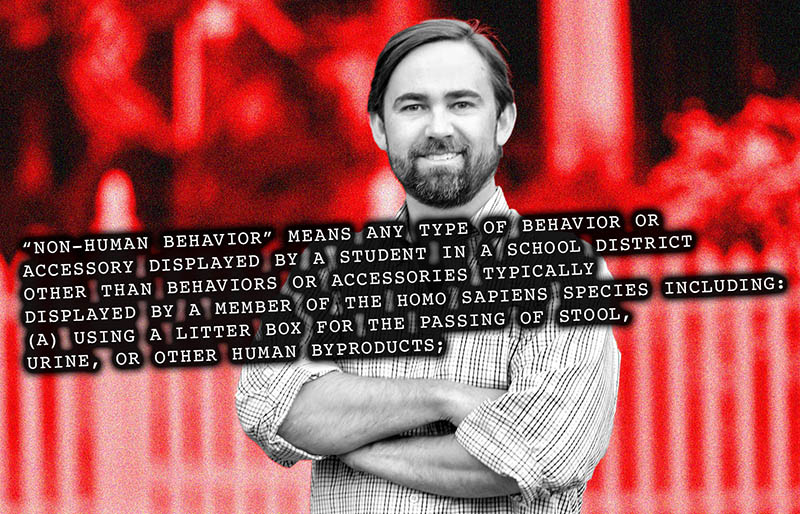

Easton burst into the public sphere when, this past April, he came out publicly during his Valedictorian speech at BYU. It was a bold, courageous move, and a risk for the political science major who had spent four years closeted at a college operated by the Church of Latter Day Saints and ranked by the Princeton Review as the second-most LGBTQ-unfriendly college in America. (College of the Ozarks, in Point Lookout, Missouri, is the first.)

Easton’s coming out made national headlines, he was invited on Ellen to tell his story, and the 24-year-old began to advocate for what he calls “living authentically.” He acknowledges he is but one drop in a very big pond, but hopes his action will have a ripple effect, helping to enact a gradual shift of attitude toward LGBTQ people from the Mormon community as a whole. Still, he doesn’t delude himself and agrees that any change on that order is going to move glacially.

“I was super afraid,” he says of the days leading up to the speech. “And even coming out after I graduated, I have had negative responses, mostly from people within my faith community. That’s been really hard to swallow, because the people who raised me, the values that they taught me, the man I am today, I owe largely to this community. And to feel most, if not all, of the negativity coming from them, is painful.”

It’s not all been negative, he’s quick to add, “I also need to acknowledge that the vast majority of people in my faith community have given me positive responses.”

His immediate family, who Easton had quietly come out to a few years earlier, has been his rock of support. “The night before the speech, I told my dad, ‘I’m going to come out in my speech tomorrow, by the way,’ and he was like, ‘Oh. Okay.’ Then, I told him I was worried how my more orthodox family members or people I really cared about would react. My dad just said, ‘You know, Matt, if people have a problem with what you’re going to do, that’s a problem with them, not a problem with you.'”

Easton remains strongly committed to his faith, and yet remains conflicted about his future as a gay man. Will he stay with the church and abide by its strict laws? Will he vocally advocate for change within its doctrine? Or will he leave, like so many other gay Mormons, so he can partake in a rich, rewarding life with a same-sex partner?

“I’m still figuring it out,” he admitted last Saturday afternoon, as he prepared to attend his first-ever Pride in Salt Lake City, later reported as the most successfully attended Pride in Utah’s history, with attendance topping 60,000. “I have prescribed completely to this religion for my entire life. It’s only recently that I’ve even been able to come out or say that this is my identity and who I am. It’s something I work through daily. For now, I’m focusing on my relationship with God and my relationship with my family. I’m just taking it a day at a time.”

Coming to Capital Pride — he’ll be here for both the Parade and Sunday’s Festival — will no doubt be an eye-opening experience for Easton, as he’ll feel what so many do at this event: engulfed by a feeling of love and belonging in an environment that is unique to the weekend.

“I’m excited to meet other people, to share my story, and to hear other stories,” he says. “Man, I just feel like a little fish in the middle of the Rocky Mountains of nowhere, so it’s definitely really cool to feel that a huge fish, an institution like Capital Pride, noticed me. It’s very validating.”

METRO WEEKLY: Let’s talk a bit about your upbringing.

MATT EASTON: I was born and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah. Both of my parents come from several generations of Mormon family, so my religion and my faith has been a very large part of my entire life. For a Mormon family, we’re not too big. I have three siblings. But both my mom and dad have six siblings, so I have 24 aunts and uncles, and 56 first cousins. It’s a very large extended family.

I lived in a very religious household. We would attend church every week and attended activities throughout the week. Many of our discussions were focused around the principles of our faith. The Mormon faith — or the LDS Church, they call it now — shaped my identity. But it also made it really difficult for me to accept and understand this other part of me, which was my sexuality.

MW: How old were you when you realized you might be gay?

EASTON: I knew from a young age. I definitely developed crushes — celebrity crushes or boys that I thought were cute. But I don’t think I had the vocabulary to express what it was. It was something we didn’t really talk about in my house or in my community. I always had this idea that I would marry a woman, have a big Mormon family, just as my parents and my siblings and my cousins had done.

After high school, I decided to serve a mission for my church. I was sent to Sydney, Australia for two years, from 18 to 20. I had a really wonderful experience doing that, but again, it wasn’t really a place where I had the chance to address my sexuality, or to even think about it. I kind of thought I’m going to move to this mission, then I’ll make it to college, and then I’ll think about it.

So after my mission, I got to college and my friends started dating. A lot of them were getting married, and I thought, “Oh, my gosh, this is the time I’ve got to figure out who I’m going to be and what I’m going to do, because these decisions are coming up fast and it’s not something I can avoid any more.” It really wasn’t until I got to BYU that I started to think about and face my sexuality a little more head on. But it was also quite complicated because at BYU, it’s not exactly an environment that’s conducive to exploring your sexuality, which made it a little more difficult for me than it might have been elsewhere.

MW: The Mormon faith historically has frowned on homosexuality.

EASTON: Yes. Only recently — probably within the past, I don’t know, 5 or 10 years — has the church begun to say being gay is not something you choose. Before then, the rhetoric was sort of that gay people are choosing to follow this path, and it’s not natural. But the Mormon Church — the LDS faith — now does say being born gay is not something you control or you choose and that there’s nothing wrong with it. You’re not sinful for being gay. But it does explicitly state that you cannot engage in homosexual activity. That means kissing someone of the same gender, dating them, marrying them, having sex with them. All of that is explicitly forbidden in the religion. You can be gay, but you can’t live gay.

MW: That’s quite the paradox. The doctrine is denying gay people a primal, human need. They’re saying you can identify as gay but you have to abstain completely from any participatory aspect of the romantic side. How do you even change a religion’s viewpoint on that?

EASTON: A very good question. You’re not the first to ask and you won’t be the last. It is tough. For myself, and for many people in my community, it’s something we struggle with. I don’t know an answer.

MW: So it begs the question, can you fully be a part of your faith if your religion doesn’t allow you to completely be who you are? How do you reconcile that?

EASTON: It sounds like you’re guiding me into a very anti-religion discussion. And I want to make it very clear that I’m not interested in bashing the faith of my family or disrespecting the community that I’ve grown up in. So please don’t frame this article in that way, because I think that would be inauthentic to who I am.

MW: I’m not trying to get you to renounce your religion. I’m just trying to explore how you personally reconcile what seems to be an impossible situation. So let me ask it this way: What is it about the Mormon faith that keeps you engaged with it despite its views on homosexuality?

EASTON: My answer to that is that I’m still figuring it out. I have prescribed completely to this religion for my entire life. It’s only recently that I’ve even been able to come out or say that this is my identity and who I am. For me, it’s something I work through daily. For now, I’m focusing on my relationship with God and my relationship with my family. I’m just taking it a day at a time. I’m really fortunate that my family has been very supportive. They just want what’s best for me. I do recognize that that’s not something that everyone has the opportunity or the privilege of having.

MW: A religion can’t just take hundreds of years of doctrine and suddenly do a hard U-turn and reverse course. Change is gradual, if at all. Do you think sticking with the LDS Church allows you to be an agent of change? Do you see yourself as someone who can help your religion better understand the truth behind what being LGBTQ is?

EASTON: I really hope so. Even during my four years at BYU, I felt a shift on campus, a change in the rhetoric, the way we talk about LGBTQ issues. For the first time this past year, the school featured a gay student on their Instagram story, then our mascot came out after he graduated. Then I came out. And just a few weeks ago, the Utah County Commissioner, a very Republican LDS man, came out as well. I feel a wave of change. I really believe and I hope that this change is coming and continues to happen.

I hope that by coming out in my speech and by being a part of this movement of other gay Mormons coming out as well, and being more true to themselves and more open and authentic, that change will continue to happen.

MW: You were not out during your school years. How difficult was that for you?

EASTON: Oh, my goodness, it was really hard. There was a lot of fear surrounding talking about my identity. I was constantly worried. Who can I trust? If I share with them that I’m gay, will they want to kick me out of BYU?

MW: Did you feel you’d be bullied or harassed by your fellow students?

EASTON: I definitely think that was a strong possibility. My freshman year, there was a boy in my international politics class. It was my second semester, his last semester. During that semester — I think it was in February — he decided to come out. He did it on Facebook. He was just like, “You know, this is who I am.” A short time later, before the end of semester, because of the response that he got, he ended up committing suicide.

So, I mean, that was a reality right in front of my face. The only gay person I knew at the time came out and that was the course of action he took. I saw that and I thought, “Is that my future? Is that all that I’m headed towards? Is there nothing brighter for me, nothing better for us as gay students?”

I will say among the group of friends who I came out to in my junior year at BYU, they were very loving and accepting, very open-minded — but I had to search for them. I don’t think it’s necessarily the status quo [to be accepting of the LGBTQ community] at BYU. Beyond that, I didn’t have much of a network or support. I think in large part it’s because there’s just not a lot of visibility at BYU. I didn’t know a lot of gay people there. I didn’t know that I could be out and open and probably be okay. I think that that was one of the hardest things. There’s not even an LGBTQ club on campus. There was one a couple years ago, and BYU removed it. It was this feeling of being alone, like maybe I was the only one, that made it so hard.

MW: Why the decision to come out, and especially in the way that you did?

EASTON: It was not an easy decision. It’s something that I thought a lot about, I prayed a lot about. I found out that I was valedictorian, and then about two weeks later, I found out that I would be the one who got to speak, so I had about three or four weeks to prepare a speech. I thought, “I’ve been given this platform, and I can give another valedictorian speech, just like anyone else, something nice that people will enjoy, but probably forget about in a day. Or I could take this platform and maybe, hopefully make something good from it, make something a little more lasting.”

I was sitting at the edge of my graduation looking forward, and I thought, “Am I going to keep living my life secretly, living in fear of what my family or my friends think?” I just realized I cannot do that. I’d done it for four years and I didn’t want to do it any longer. I thought if I came out here, there would be no looking back, and it would help me to get out of the closet and live more authentically.

I spoke a little bit about this on Ellen, but I also was very concerned about other students who are in my same situation — you know, freshmen who are at BYU who are also gay who maybe just came back from their missions and are just beginning to address their sexuality. I had a lot of dark nights, and a long time of feeling really alone, and so I thought if I could give this speech and say something that those freshmen or sophomores at BYU — those queer students — are going to hear, they’re going to feel a little less alone. It’s not just that we can survive BYU, it’s that BYU needs us. Our school needs the brilliant minds of other queer students. I wanted to help them know that they are important. We’re not just something to be cast to the side.

MW: Did anybody afterwards criticize you or come to you and say you shouldn’t have done that?

EASTON: Yeah, people have. It’s mostly just been trolls on the internet, old people who read a headline and didn’t listen to the whole speech and feel the need to message me. But the people who are important to me — my professors, my aunts and uncles, people who I actually care about — I’ve had nothing but support from.

MW: Were school officials aware of what you were going to do ahead of time?

EASTON: They were, yeah. The assistant Dean read it and approved it. I thought, “You know, he’s probably going to say ‘Maybe it’s a little too controversial.'” But I didn’t get a single critique back. He just sent me an email that said, “This is awesome, I think everything that you want to say is appropriate, so go for it.”

I’m going to be honest: I was very surprised. I honestly thought that they were going to stop me. But I didn’t say anything that goes against what current LDS doctrine says. I didn’t try to do that. All I said in my speech was “I’m gay, this is who I am, and that’s who God made me.”

MW: How devout are you currently?

EASTON: I’m still attending church. I think to reiterate what I said earlier, now is a time that I’m really focusing on my relationship with God and my spirituality. I’m still working through my feelings with my religion and these questions of do I want to remain in this religion? Is it going to be a better quality of life for me to leave? I’m not certain yet, if I’m being completely honest. So, for right now, what I’m doing is focusing on what I do know and what I do believe. These other questions, I’m okay with taking them piece by piece.

MW: Is a relationship and possibly marriage to a man something you can even envision for yourself down the line?

EASTON: I’ve spent so many nights, in college or even growing up, where I’ve spiraled into these huge cases of hypotheticals or possibilities. I get so caught up in looking forward to the future that right now, all I’m really focused on is stepping back and focusing on the day-to-day. That’s a very roundabout way of answering your question.

MW: What does Pride mean to you?

EASTON: For me, pride means authenticity. It means being proud of who you are and accepting exactly where you’re at. This is the first time I’ve really felt proud of who I am. It feels really good. I had no idea what it could feel like, and I never want to let go of that.

Matt Easton is one of the Grand Marshals of this year’s Capital Pride Parade, along with Earline Budd, Brandon Wolf, and Hailie Sahar and Dominique Jackson from the FX show, Pose. The Parade kicks off Saturday, June 8, at 4:30 p.m. at the intersection of 23rd and P St. NW. See page 10 of this magazine or visit www.capitalpride.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.