Sex & The Single Ryan: An Interview With Ryan J. Haddad

The writer and star of "Hi, Are You Single?," Ryan J. Haddad is a gay man like any other in search of love, with one key difference.

By Randy Shulman on April 6, 2022 @RandyShulman

There is a moment in Ryan J. Haddad’s stunning, insightful, potently honest one-person show Hi, Are You Single? in which the actor, after a string of awkward, strikingly rude encounters at gay bars, turns to the audience, and offers a shattering revelation.

“I never had to apologize for the space I was taking,” he says of his family life in Cleveland, Ohio.

“If you are born and you have a disability and your family is ashamed of that, or looks down on that, or pities you, or thinks the only value you have is the inspiration that you offer just by existing, then you’re going to have a rougher time of moving through the world,” says Haddad, who has cerebral palsy, a disability that limits his motor functions and musculature. “Because that’s not what we are. And that’s not what disability should be.”

Haddad, 30, “was really dealt a wonderful family, both in regards to being gay and being disabled,” and notes that that particular line in the play is directly tied to his upbringing.

“When you enter gay spaces, whether they are bars and clubs or online apps or the web,” he says, “and suddenly you’re made to feel like you don’t belong because there’s a giant staircase, it’s a real culture shock.

“The hard part is that I came out of 16. I was out and proud to be gay from the moment I was 16. I had five years of ‘I’m gay. I’m gay. Isn’t it great?’ And then I’m 21 and I walk into a [New York] gay bar for the time and the apologizing starts. Suddenly I’m apologizing. Suddenly, is it okay? I mean, I have cerebral palsy — is that okay?

“My upbringing gave me ambition, drive, work ethics, knowing how fabulous I was, feeling unconditional love from an extended family that is not even countable,” he continues. “Moving away, I realized the way that I was taught to see myself is not the way that strangers see me, or see my friends who are also disabled. So ‘I never had to apologize for the space I was taking’ is an artifact of a younger, more naive Ryan.”

Hi, Are You Single? is currently in the midst of a world premiere, live, in-person run at Woolly Mammoth, co-producing with L.A.’s IAMA Theatre. (A beautifully produced, recorded version of the show ran in early 2021.) The opportunity to perform before a live audience for two weeks has left Haddad simultaneously elated and anxious.

“It’s strange that I should say this about a show that I’ve been doing for seven years, but it is officially the world premiere production, because [Woolly is] the first theater that said, ‘We don’t want you to just come for two or three days and throw it up. We’re going to produce it, fully produce it,” he says.

“I’m extremely grateful to get to do a run of 13 performances, plus a reading of my new play, Hold Me in the Water and stretch that muscle as a performer, because I’ve never had to do that many shows at once of anything in a row. And so I’m learning and I’m growing and my performance will undoubtedly grow and change over these 13 performances.”

“I feel that what Ryan is doing is making the invisible visible through his story,” says Maria Manuela Goyanes, Artistic Director of Woolly Mammoth. “Last night, at our first preview, I was sitting next to someone who, it turns out, has spina bifida. I talked to her afterward and she literally was like, ‘I am going to have any boy I want to date see this show before I date them so that they understand what my experience has been in the dating community.’

“Folks who are looking for love in the disabled community often face a lot of discrimination,” she continues. “So it’s just clear to me that Ryan is a real pioneer… and I know that there are people who deeply relate to what he is talking about and have never seen themselves on stage before.”

Hi, Are You Single? not only showcases Haddad’s magnificent writing, but his cunning ability as a performer to fully connect with an audience, showcasing an astonishing range of moods and emotion within the span of a tightly-constructed hour. The narrative is comprised of small vignettes that bloom into big, beautiful, emotionally resonating moments, casting a light on the LGBTQ community, the disabled community, and the struggle to find love, happiness, and a satisfying sexual connection.

Haddad reflects a mirror on how society views him, but there is also a pivotal moment (that won’t be spoiled here) in which he turns that mirror on himself. The results are revelatory.

“If you see somebody who’s different that isn’t part of the picture that you had in your mind for what your life would be, you run in the other direction,” says Haddad. “And that can manifest in pain and hurt feelings and rejection, regardless of your reasons for behaving the way that you have toward another person.”

Haddad is already familiar to television audiences, having appeared in two seasons of the Netflix comedy, The Politician, and is about to embark on shooting The Retreat, a miniseries starring Harris Dickinson (Beach Rats) and Clive Owen. He feels that all too often disabled roles are still going to non-disabled actors.

“I think we’re getting better, but we’re not there yet,” he says. “We haven’t arrived at the moment of, ‘No, no, we will not cast a non-disabled person in a disabled role.’ It’s still accepted in many instances.”

Goyanes, for her part, is hopeful this will change as the result of actors like Haddad.

“I always fear that sometimes these things can be blips, where it happens for a while and then it stops happening,” she says. “But I want to see more of it. And I’m so excited to be part of the theaters who are championing this, wanting to make sure that there is inclusivity in terms of disability on our stages and in our generative artists.”

METRO WEEKLY: How long have you been performing this particular show?

RYAN J. HADDAD: Since 2015. It was my senior capstone in undergrad. So it started academically, but it always was a project that I knew was going to catapult me into the professional phase of my career. Now, I didn’t know where that was going to happen, or how that was going to happen, but I wanted to finish college — at the advice of Tim Miller, my mentor in solo performance — with something that I could hold onto and that could showcase me. That’s what this was and that’s what this has been. But it’s also a really important story, of course, and is something that I’m really proud of and that we’ve been revising and retooling and shaping and crafting for the past seven years.

MW: What is it about Hi, Are You Single that you think makes it right for Woolly Mammoth, which has a very specific, often offbeat framework for what it produces?

HADDAD: I think it’s because of its edginess. I think it’s because it’s sexy and it’s darkly funny. And the character of Ryan is a disabled protagonist, which is very rare to begin with. But he’s the kind of disabled protagonist that we never really see on stage or screen, in that he is fallible, he is flawed, he is longing for something that he feels is just out of reach. And he’s not afraid to own his own mistakes.

Typically, disability is portrayed as sugar-coated or soft, or “Isn’t it nice that this person is here” and, “Oh, how wonderful. They could never do anything wrong, they’re disabled,” making us infantile and angelic. I’ve never been interested in that. That’s never been my life. That’s never been my experience. I think that’s very clear [in the play].

MW: The show does not treat the disabled community or the gay community with kid gloves.

HADDAD: Not at all, not at all. No, no, no. It’s the intersectionality of “I come from two communities and I’m going to take one of them and I’m really going to put them to task — including myself within the gay community.” There was no way to do this show without calling out the discrimination that gay men in particularly levy at each other.

MW: You refer to Ryan as a character, but I felt while watching it, that I was watching you, hearing your experiences. How much of it is autobiographical?

HADDAD: It’s all autobiographical. It all happened to me over the last nine years. You are watching a version of me, of course. But it’s all based on a true story, as they say, individual vignettes that are then crafted in an order that don’t come chronologically in the way that they happened. Sometimes there are events that are hybrid. One scene holds two or three different happenings in it. But beyond that, it’s certainly not fiction. I call him a character because I’m giving a performance. And because, over the course of the play, he has to go on a journey and has to sort of achieve an arc in order for the audience to leave feeling satisfied.

I’m an actor. I’m acting and I’m playing a character. And that character is a younger version of myself, or the current adult version of myself looking back on these things that happened over the past decade or so. I also call him a character because I’m an autobiographical playwright with multiple plays. There is a character of Ryan in all of these plays. There are now four projects, which are in various, viable stages of professional playwriting development. And in every one, Ryan is on a different journey, but it is the same character. They’re different stories and different crevices of his life.

I don’t talk in the third person to sound like a pretentious asshole, but it is acting. Heidi Schreck said this when she was doing her brilliant, What The Constitution Means To Me as herself, which, of course, is now on the road with other actors doing it. But when she was doing it, she said it is a performance. She said, “I’m an actor and I’m doing a carefully crafted, calibrated performance in collaboration with my director.” I feel the same way. So that’s what I mean, but it isn’t a work of fiction. It is a work of — I will call it creative nonfiction which is built to be a narrative that is satisfying, all based on true events.

MW: Can you envision another actor playing the role at some point?

HADDAD: I have, and I think the answer will eventually be yes. But I don’t think it’s going to be tomorrow or the next day or the next year or maybe even in the next ten years because I think I can — especially now that I have [my new play] Hold Me in the Water to sort of do in repertory with it — I think I can inhabit this role for a while still. At some point I’m going to age out of it. And, of course, I want to be willing to give it to the disabled theater and performance community. But I’m not ready to hand it over yet.

MW: You’ve been doing the show off and on for all these years, but Woolly marks the official world premiere, with a longer consecutive run.

HADDAD: I’ve done it here for one night and there for two nights over the years, and every time I would do it, I would be revisiting it fresh, because it would be months or even a year after I had done it the last time.

But now, to just get to do it in a row for different people, it’s a muscle that is new for me. I’m excited and I’m a little terrified, but thrilled to have the opportunity, and just very excited to engage with the audience in a real, viable relationship over these evenings and afternoons.

MW: You are frequently in motion throughout the hour. It is not a static show.

HADDAD: I wanted that. This production is directed by Laura Savia, who’s been doing it with me for the last seven years. I wanted the movement because of the way that I feel when I watch a solo work, honestly. I get bored very easily in the theater. You have to grab my attention either with a exhilarating performance or a riveting plot that draws me in and makes me pay attention. So from even back when I was in college, before I had Laura as the director, I knew I wanted to move around the stage because it was important for the audience to see my movement and my mobility. Also, I wanted to give them visual interest. I wanted to give them a variety to my performance and not just sit in a chair.

But I do recognize that when I step out of the walker or I’m walking toward the bar, or I’m pushing out of a couch, or I’m putting on a blazer, you’re watching me in real time, a person with a body that’s different than yours. And I’m totally aware of all the levels that it works on. But, for me, it’s just, “Well, I’ve got to put this coat on now. I’ve got to get to the couch. I’ve got to get to the table.” What I’m talking about is my organic movement from Point A to Point B.

If it was played by a person who was not disabled, the groundbreaking revelatory lauded nature of their performance would just be the ways in which they can mimic me crossing a stage. And that’s not a performance, that’s just putting on disability drag or what we call “cripface.”

It’s insulting, and it shouldn’t be something as a performer, that you have to think about, because I have to tell you, my movement on the stage is truly the farthest thing from my mind, except for when I’m pushing off the couch. Then I have to think about, “All right, well I got to make sure my feet are in the position so that when I push off, it doesn’t take me 10 minutes, but it takes me 15 seconds.”

But I’m not thinking about any of that. And if it was a non-disabled actor in this part, that’s what would be dominating their mind. I’m thinking about what does the character want? How is the character achieving that? How does the character feel when he’s rejected or when he does the rejecting? Or what needs to flash through my eyes or come across my face to make the audience feel a certain way? This is what actors do. And when you layer on, “Oh, I’m going to play disabled,” that becomes what the performance is about and it dehumanizes the character because the character themselves would not be thinking about those things at all. Okay, I’m off my soapbox for the moment. Thank you.

MW: I want to explore your life history a bit. You are from Cleveland, Ohio. What was your life like growing up?

HADDAD: I was feisty. I knew what I wanted from the time I was a very small child. I wanted to be putting on plays and telling stories, and I didn’t know how it would manifest, but here we are. I had a very supportive family that, if they had to work through any of their own emotions about having a child or grandchild or niece or nephew or sibling with a disability, they did that all behind the scenes. I never had to deal with that. I was not treated differently by my family because I was disabled.

I’m the youngest of three boys. And I might have been a little spoiled, but also that could be because I was a budding homosexual prima donna, too. It had nothing to do with my disability, but I had to do good in school. I had to get straight A’s. I had to take all the honors classes. My parents ingrained in me that if I wanted to achieve my dreams — or achieve anything — that I had to do the absolute best that I could and work hard.

And yes, I’m very fortunate to have had the opportunities that I’ve had, but also I wouldn’t have accepted any less for myself at this point because of the way that I was raised. And I’m not saying I was in the strictest household in the world. I have incredibly loving parents who would bend over backwards to do anything for me then — and now. But they wanted me to do well, and therefore I, as an adult, wanted myself to do well. And if something isn’t happening or a play is not taking off, or I’m not getting the role that I want, I have this ambition and this drive that I really do think exists because of my parents and my brothers.

MW: What made you gravitate towards acting?

HADDAD: Oh, my God, because I would watch movies and TV shows and I wanted to do that! As soon as I started seeing plays — my first play was The Red Shoes at the Cleveland Playhouse with my aunt Janice, at the Children’s Theater Series. And then my first play on the big, big stage was the touring production of Beauty and The Beast with my grandparents. And then my parents took me to New York all the time.

Until I had access to the actual theater, it was, “I want to do what they’re doing on the screen.” And then I saw plays and musicals, and it was, “I want to do what they’re doing. I want to do what they’re doing.” I didn’t know what the path was and I also didn’t see anyone who looked like me doing it, having a disability and being in a musical. For many years, I didn’t think it was possible to be in a musical. And even now, I have a nice singing voice, but my vocal range is — from the high note to the low note — somewhat limited. I’m not going to be doing a Bernadette Peters score. But there was so much that I wanted to do that I didn’t see reflected. And as a little kid, I didn’t care.

I did see myself in characters like the Disney princesses, or in the wicked stepmother or the evil queen. I rarely saw myself as the prince. Isn’t that interesting? I wanted to find my Prince Charming, of course, but I didn’t need to see disability to see myself in those [other] characters. It was just that when I started to get older — 11, 12, 13 — that the reality of what might it be to actually work professionally hit me.

I’m an actor. I’m arguably more known for being on television than I am for being a writer-performer on the stage. But it’s no secret that the reason I have a career at all is because I wrote my way toward a career with this play and the subsequent plays that have yet to be produced but will be soon, and the stories that I keep telling.

I had my first big moment on TV and I thought, “Oh my God, the roles are just going to keep coming!” And then there were two years of rejection as an actor. And the reason that I don’t throw in the towel and give up in those moments is because I also have control over as a writer.

I’m still waiting for people to say yes to doing my plays, and I’m building the next thing, and I’m building the next job opportunity. Not only for me. I make something and then a whole group of people come together to build that thing that I’ve written. When I’m writing, I’m in the driver’s seat and it’s part of why I don’t get too down on myself when I don’t get a role.

Of course I get depressed. Of course I get sad. Of course I say, “Is acting really for me?” Because I think the industry thinks that they’re ready for more disabled representation, and then, when they have a disabled actor in front of them for a role that they didn’t write to be disabled, they freak out and don’t know what to do because that wasn’t the vision that was in their head.

As a disabled person, you are used to adaptation, so I can read a role and be like, “Of course I can play this role.” And I do well and my tapes are good and I know casting directors often send them on to producers and writers, and then a lot of times they stop there. And this sounds like I’m complaining, but I’m not. I’m working a lot. I’m currently filming a TV show and I’m on a three-week hiatus to be able to come and do this here at Woolly Mammoth.

MW: It doesn’t sound like you’re complaining. It sounds like the industry has some growing to do.

HADDAD: I think that other disabled performers would read this and go, “Oh, my God, shut the fuck up!” But the thesis of what I’m trying to say is that I am an actor, but 70 to 75 percent of the work I do on a daily basis or a monthly basis or a yearly basis is writing my way towards an acting opportunity that I have created for myself.

MW: I think your show should be seen by all audiences, but I specifically would love to encourage a gay male audience to see it, because it does highlight, at certain points, the judgemental side of who we are and the hurt that we inflict on one another through rejection. Can you briefly reflect on that aspect of the show?

HADDAD: I think that we are trying to fit into a society that still by and large detests our existence. We still live in a country where a major pillar of one out of two political parties is detonating our rights and dehumanizing us, trans people even more so. I mean, I’m talking in the LGBT community at large, this is where we still sort of are. So even though two cisgender men and two cisgender women have been mainstreamed in a way that is more present in the media and feels more accepted, there’s still a huge portion of this country and one major political party — lots and lots of people — that just don’t think we have a right to exist.

So I think gay men are trying to operate in this mode of self-preservation. When they see somebody that is different and I’m a part of that community, and in the play, I don’t shy away from my own prejudices and discrimination, so it has to be an inclusive statement — I’m not saying that I am a victim. But I do think we’re acting out of this kind of self-preservation where we just want to live the lives that we fashion for ourselves.

Whether that’s super-traditional and very heteronormative, or one that is more open and queer and “choose your own rules” and “build your own happiness,” we’re still trying to survive and thrive in a country and world where we are persecuted all the time, and where bills and legislation and even just people’s individual behavior is such that we are not always made to feel like we are worthy of happiness or that we are even made to feel safe.

So, I think when we see people who are different, or when men see me and a disability, that’s not part of the life that they envisioned for themselves, even if they are attracted to me physically. I will say the gay community is exclusive and somewhat exclusionary. If you’re older or you’re heavier or you are more feminine or you’re HIV-positive or you are short or you don’t have muscle or you don’t have hair. And then we get into these sort of types, right? Preferences. Well, sometimes the preference is a preference and the preference is what makes you aroused, and other times a preference is just plainly discriminatory.

I’m not a psychologist, I’m not a scientist, but I think it is rooted in that we’re trying to survive and thrive, and if you see somebody who’s different that isn’t part of the picture that you had in your mind for what your life would be, then you run in the other direction. And that can manifest in pain and hurt feelings and rejection, regardless of your reasons for behaving the way that you have toward another person.

The truth is, I’m a gay disabled man, and when I walk into a gay space as a disabled man, I’m not welcome. I’m not welcome, still. And I have more confidence now to stake my place and not apologize, but I’m still made to feel — with unspoken glances, looks, stares, or non-communication — I’m still made to feel like I don’t belong there.

MW: Do you think any of this will ever change? Do you think we’ll evolve as a society to get to a better place?

HADDAD: Yes, I hope so. I don’t think my play is not going to change the world, but I think the more and more we put disabled people on our stages, on our screens, in our literature, in the arts as a whole, in the mass media popular culture consumption, it’s going to change people’s points of view and their hearts and their minds.

We just have to be careful about the ways in which we do that storytelling so that it doesn’t veer into the ableist lens of inspiration only, or angelic or infantilized or dehumanized, and only as a source of good thoughts. We got to tell stories about real, full, rich characters with complex lives and complex human emotions that can fuck up from time to time. The more that happens, the better off, I think, we’re going to be.

Hi, Are You Single? runs through April 10 at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, 641 D St. NW. For tickets, call 202-393-3939 or visit www.woollymammoth.net.

Ryan will be doing a free reading of his new play Hold Me in the Water at Woolly on Wednesday, April 6, at 8 p.m. Reservations are required. Click Here to reserve.

Follow Ryan on Twitter at @ryanjhaddad.

Gallery: The Emotionally Sensual Artwork of Soltian

Peacocks, rabbits, and hamsters dominate the art of Soltian, typified by a vast range of emotions, from aggressive to melancholic to serene.

By Randy Shulman on March 30, 2025 @RandyShulman

Rabbits, as well as other animals -- peacocks, hamsters, and cats -- dominate her work, which is typified by a vast range of emotions, from aggressive to melancholic to serene.

"I'm always going for some kind of loud sort of expression," she says. "My illustrations tend to be very suggestive or very erotic or very cute. It's always about some kind of sensual pleasure or dramatic pain."

A librarian by trade -- she currently works at the National Institute of Medicine -- Soltian nonetheless treats her art as a full-time vocation. Her online store, which describes her as a "crafter of indulgences," sells various items based on her works, including pendants, keychains, and even life-sized pillowcases featuring popular comic book characters, such as Nightwing, with whom she admits to being somewhat obsessed.

Gays in ‘Greatest Danger I Have Ever Seen’ says Russell T Davies

The "Doctor Who" showrunner warns that Donald Trump's election is a symptom of a massive and hateful global anti-LGBTQ backlash.

By John Riley on March 19, 2025 @JRileyMW

Russell T Davies, creator of the British TV series Queer as Folk and the current showrunner of the BBC phenom Doctor Who, says gay society is facing dire peril ever since the presidential election of Donald Trump in November, 2024.

"I'm not being alarmist," Davies told the British newspaper The Guardian. "I'm 61 years old. I know gay society very, very well, and I think we're in the greatest danger I have ever seen."

Davies said the rise in anti-LGBTQ hostility is not limited to the United States, where Trump has signed various anti-LGBTQ executive orders, many geared to diminish and seemingly eradicate the transgender community.

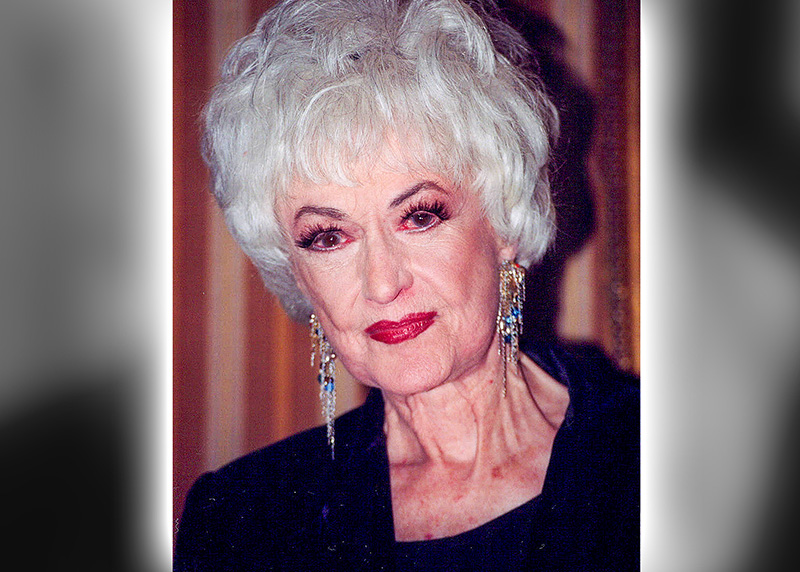

Bea Arthur’s Air Force Bio Purged by Department of Defense

The DOD removed a page on actress Bea Arthur's military service to purge references to diversity and LGBTQ content.

By John Riley on March 27, 2025 @JRileyMW

A page touting Golden Girls actress Bea Arthur's military service during World War II was reportedly scrubbed from the U.S. Department of Defense website as part of the Trump administration's overzealous efforts to purge anything related to diversity or LGBTQ identity.

Last week, X user @swiftillery noted that the article on Arthur -- first published in October 2021 -- had been removed from the Defense Department website.

According to The Advocate, the Internet Archive documented a "404 -- Page Not Found" message at the URL where the article had been housed.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

The Magazine

-

Most Popular

Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal

Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal  Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration

Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration  MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates

MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates  Police Barge into Walmart Restroom to Confront Butch Lesbian

Police Barge into Walmart Restroom to Confront Butch Lesbian  Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures

Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures  'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches

'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches  Open vs. Monogamous Love: What the Research Really Says

Open vs. Monogamous Love: What the Research Really Says  Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya

Hugh Bonneville Delivers a Show-Stopping Vanya  Trans Woman Arrested For Using Women’s Bathroom to Wash Hands

Trans Woman Arrested For Using Women’s Bathroom to Wash Hands  Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer

Transgender Blackhawk Pilot Sues Right-Wing Influencer

Becca Balint: The Pride of Vermont

Becca Balint: The Pride of Vermont  Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration

Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration  MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates

MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates  A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'

A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'  Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'

Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'  'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches

'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches  Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban

Jared Polis Signs Law Repealing Colorado's Gay Marriage Ban  White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures

White House Ignores Reporters with Pronouns in Email Signatures  White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"

White House Demands NIH Study Transgender Transition "Regret"  Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures

Air Force Reverses Ban on Pronouns in Email Signatures

Scene

Metro Weekly

Washington's LGBTQ Magazine

P.O. Box 11559

Washington, DC 20008 (202) 638-6830

About Us pageFollow Us:

· Facebook

· Twitter

· Flipboard

· YouTube

· Instagram

· RSS News | RSS SceneArchives

Copyright ©2024 Jansi LLC.

You must be logged in to post a comment.