Pulse Survivor Brandon Wolf is Fulfilling His Promise

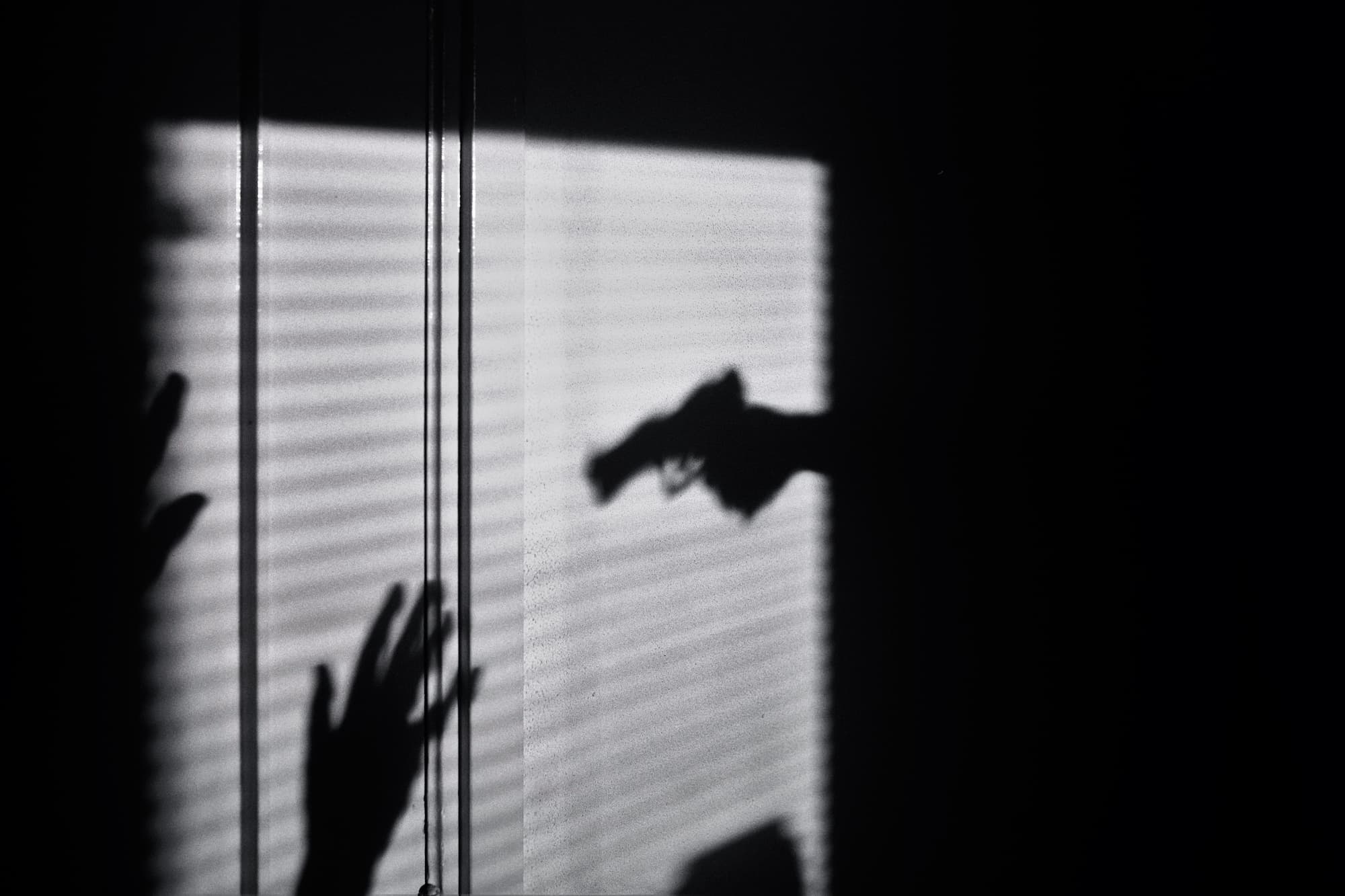

Brandon Wolf on the tragic night that changed his life, and why the LGBTQ community must remain vigilant in its fight.

“On Monday, June 13, 2016, I felt I didn’t even know whether or not it would be worth living to see Tuesday,” says Brandon Wolf. “There was a part of me that hoped that when I fell asleep, I never woke back up again.”

The 33-year-old gun safety and LGBTQ advocate was one of the survivors of the deadly Pulse nightclub massacre that occurred on June 12 of that year in Orlando, Florida.

For Wolf, who lost his friends Christopher Andrew Leinonen — known as “Drew” — and Juan Guerrero in the mass shooting, his grief was almost insurmountable. But he credits the LGBTQ community with standing by him during a difficult time and providing the support he needed to resume his regular life.

“Six days after the shooting, we had a funeral service for Drew and it was beautiful,” he recalls. “I wrote my eulogy in the front seat of my car, and my hand was shaking so much I could barely steady the pen. And his mom had asked me to be a pallbearer that day, which I’m still really grateful for, to this day.

“As I was helping to push his casket down the aisle, I found myself gripping the side of it really tightly. I think it’s because I didn’t want to let go of my best friend until I’d found the right words to say goodbye. We got to the front of the church, and I looked down at this really beautiful polished wooden casket. And I made a very quiet promise. I promised Drew, in that moment, that I would never stop fighting for a world that he would be proud of.”

Wolf subsequently became involved in The Dru Project, an LGBTQ youth organization named in honor of Leinonen, which has given over $150,000 in college scholarships to LGBTQ youth, as well as mini-grants for Gay-Straight Alliances and out-of-work drag entertainers during the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

On a larger scale, Wolf also became a visible activist on the issues of LGBTQ rights and gun safety, sharing his personal story in interviews with media, at pro-gun reform rallies and demonstrations, and lobbying lawmakers to pass gun restrictions.

“My first foray into being a vocal advocate for gun reform was during the 2016 election cycle,” Wolf says. “A few months after Pulse, I learned that Senator Marco Rubio — who had initially said he was not going to run for re-election to the Senate — had reversed course and decided, after being absolutely humiliated in the presidential campaign, that he would try to run for re-election, citing the shooting at Pulse and the horrific loss of life as a reason why he was seeking another term.

“I was infuriated, because this is a man who had never once reached out, never once made overtures to try to understand us, our stories, our pain, what we needed in terms of healing,” Wolf continues.

“And on top of that, this is a man who fundamentally does not believe in changing anything. He has taken over $3 million from the NRA. He’s good to go with guns anywhere for anyone who wants one. And it didn’t make any sense to me that this person could so boldly lie to people about why he was trying to salvage his political career.”

As a result, Wolf ended up volunteering for U.S. Rep. Patrick Murphy’s campaign for the U.S. Senate against Rubio. He also began engaging with gun violence prevention organizations, including the D.C.-based Pride Fund to End Gun Violence and the national organization Everytown for Gun Safety. In 2018, he was involved with the March for Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C., which had been sparked by another mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Following a successful election cycle that saw a number of pro-gun reform candidates elected to Congress, Wolf became the first Pulse survivor to testify before a U.S. House of Representatives committee.

Cathy Renna, a public relations consultant who serves as communications director for the National LGBTQ Task Force, recalls meeting Wolf when he was working with organizers of the March for Our Lives, including the teenage survivors of the Parkland mass shooting.

“Brandon is one of those individuals who turned a horrible, horrific situation around, not only to honor the memory of his friends and the people lost at the Pulse shooting, but to turn it into something positive, into a life of activism,” says Renna. “For someone to go through what he went through, and to come out of it with a desire for change, a desire to reach people, to try and make sure it didn’t happen again, and to continue to do that, is remarkable.

“The term that gets used all the time is ‘accidental activist,'” she continues. “But it was no accident. I think he always had it in him. He had a passion for the community. He had an extraordinarily powerful sense of self and an extraordinarily powerful sense of how our community is a family. He found a way to create a bridge with other communities that had also suffered the nightmare of gun violence, and was able to broaden the conversation in a way that is not always so easy to do.”

Wolf has since taken a job as press secretary for Equality Florida, utilizing his talents to get out the statewide LGBTQ advocacy organization’s message to the media and the larger public.

“I was really thrilled when I learned that he was going to join the staff of Equality Florida, particularly in a media capacity, because he is so skilled at leveraging media and messaging across communities to educate folks about why they should care about gun control, or why, in this case, they need to care about trans youth,” says Renna. “I cannot think of a more powerful person to lead the charge [for LGBTQ rights] in Florida than Brandon.”

METRO WEEKLY: Let’s start with your childhood. Where did you grow up?

BRANDON WOLF: I grew up in a small town outside of Portland, Oregon. And when I tell people that I’m from Portland, they often get this idea — this mental picture — of what my childhood must have been like. They imagine that it had lots of pink hair and tattoos and craft beer. And while that may be true for bits of the Portland Metro area, I grew up in a really small town with maybe a handful of stop lights, the kind of town where you go to school with the same people all the way from kindergarten until you graduate high school.

Childhood for me was a really long struggle to fit in. The town I grew up in didn’t really look a lot like me, it didn’t really love a lot like me. And as a result, I often felt like a stranger who had overstayed his welcome.

When I graduated high school, there were two thousand students in our school, and of those two thousand students, eleven of us were black. And there were even fewer than that who were out as LGBTQ. And so, while I am grateful for a lot of the things that I got from my childhood experience — I had lots of opportunities to be in leadership spaces — it also left me feeling extremely isolated and lonely.

MW: What was your coming out process like?

WOLF: I came out to a few friends in my junior year of high school and found a small LGBTQ community at my school, but I wasn’t really publicly out until senior year. Part of that process involved being outed by an elder in our church.

My mom passed away when I was 11 years old, and this person who eventually outed me to others in the community had been one who had taken care of me after my mom passed away — she babysat me after school. And so, much like the current political climate, part of being forced out of the closet was an insinuation that I was a threat to my classmates, that simply by existing, I was contagious or that I was indoctrinating people, that I had an agenda for other people to identify as LGBTQ. As a result, there was panic in the community.

That single person outing me led to people being pulled from my classes, from after-school activities with me. It led to protests at the end of the school year, with parents and students demanding my resignation as student body president. Ultimately, I carried out my duties through graduation, but even my graduation speech was, in part, censored because the school was concerned about how me being honest about my identity might impact the ceremony.

MW: How did you rebound from that? Do you still carry some of that trauma with you?

WOLF: Well, the truth is, I practically ran away. I went to college in search of some semblance of belonging and in search of a more diverse community. And while I found a little bit of that, I did go to college about two hours from where I grew up. And when you go to school two hours from home at a state college, it looks a lot like high school, and it feels a lot like high school. As a result, I still didn’t quite feel like I belonged. I still didn’t quite feel like I fit in. So in the summer of 2008, I auditioned for a job at Disney. I got a call a couple of weeks later, they offered me a contract in Orlando, and that’s when I moved, and I’ve not moved back.

MW: What was it like working at Disney?

WOLF: I worked at Disney from 2008 until the end of 2012. There were periods when I was seasonal or part-time, but for a good chunk of that time, I was a full-time cast member. I worked in the entertainment department. I danced in parades and shows, and it was an incredible once-in-a-lifetime experience. I met a lot of the incredible people that I know now, especially the LGBTQ people and people of color who I’ve come to know and love.

Disney gave me an opportunity to find a new community. That is not an evaluation of them as a corporation or an employer, but simply my personal experience with the kind of community that we formed inside the ranks at Disney.

MW: What is the Orlando LGBTQ community like, and how did you find your niche within it?

WOLF: It was nothing like I had ever imagined possible. When I was growing up, adults would often tell me that the world was not going to be ready for someone like me, that I was always going to have to tone down bits of myself, that I was going to have to deepen my voice, stiffen my wrists, move incognito if I wanted to be successful in the world. I had dreams at one point of being in the music industry, and I remember this guy once told me that I may be talented, but I was always going to be too gay to be in the music industry. So there was that fundamental struggle with how do I find my way in a world that doesn’t have room for all of me?

When I got to Orlando, it was entirely different. It was the first time I had seen such a diverse, melting pot of people. It’s the first time I had ever seen so many people who looked like me, so many people who identified the way I identified, and that was when, for the first time, I felt at home. And that continues to be true. Orlando is a beautiful, diverse, talent-rich place and I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else.

I would say the Orlando LGBTQ community was not only a refuge for me back then, an oasis that I didn’t imagine possible, but that [feeling] has only continued to grow stronger, even in the face of some pretty horrific anti-LGBTQ backlash in the last few years.

MW: Let’s talk about your friends and the relationships you formed prior to the night of the Pulse shooting.

WOLF: For me, Orlando became that first real taste of a “safe space,” and it came in a couple of different ways. It came in this workplace environment which, for the first time, celebrated who I was instead of telling me to tone it down. It came in bars and clubs and spaces that were created specifically for people like me. It also came in the form of a chosen family. I was familiar with that term before moving to Orlando, obviously, but I wasn’t familiar with what that really felt like until I got to Orlando. I met my best friend in 2014. And though I didn’t know it at the time, he changed my life the very first time I met him.

We met on a blind date — well, sort of a half-blind date because I had been Instagram stalking him for weeks. When I saw that we had a mutual friend liking all of his photos, I went out on a limb and asked him if he would set us up on a date. So the first time I met Drew was on a half-blind date at P.F. Chang’s at the Millennium Mall.

We were sitting, waiting for our table. He was drinking out of a martini glass and he said, “I have a question for you.” And I thought, “Okay, fire away.” And he said, “What are your thoughts on the for-profit health care industry in America and its impact on consumers?” And I was stunned, because I’m expecting him to ask what my favorite color is.

I had had a couple sips of my liquid courage and I answered him. I told him everything I thought about for-profit health care. And that became an entire night of talking about political issues and personal struggles. It was awe-inspiring because in front of me was an openly queer person of color who was unashamed of who he was. Throughout the entire conversation, he never once looked over his shoulder to see if the table behind us might have overheard him talking about an old fling. He never once lowered his voice or stiffened his wrist to try to avoid being detected. He was just out and proud, and I had not experienced that before. I had never been in the aura of someone who was so unashamed of who they were. We became best friends almost overnight. I just wanted to be close to that energy as much as possible. I wanted to understand it. I wanted to know how to tap into it myself, and I did.

Drew taught me to challenge the status quo. He taught me to be proud of who I was. I think he’s the first person that told me it’s okay to love yourself exactly as you are. And he also introduced me to a new world of people that were similar to him.

He met his partner Juan in 2015. And while I did all the things that a good and skeptical best friend should do, like cornering him in a bar one night and making sure to tell him a hundred times not to break my best friend’s heart, giving him the wrong address to a restaurant once or twice just to see if he would show up, doing all of the things to put Juan through the wringer, at the end of the day, it was impossible not to love him exactly as much as you love Drew because they had that same energy. That was a testament to the kind of people that Drew chose to surround himself with. He unlocked an entirely new world to me of people who were just proud to be themselves.

MW: Let’s talk about the night of the shooting. Walk through what happened.

WOLF: In this community, we often refer to June 11th as the “last normal day.” It was, in every way, a normal Saturday. It was laundry day, which meant I was folding socks and underwear on the couch. Drew and Juan were on a date at SeaWorld. I was in my scrubs, nursing a champagne hangover from the night before and seeing their cute pictures in front of roller coasters, feeling a little annoyed that I was looking so scrubby.

It was a warm day, so I spent some time by the pool that afternoon. As the day wound to a close, I texted Drew and Juan and asked if they wanted to go and get a drink. They got to my apartment just before midnight, it was probably around 11 o’clock, which was a little late for us. We usually like to get an earlier start. We listened to the same playlist that Drew always made us listen to. We watched these weird music videos that Drew always put on a loop on the TV in the background.

There was one difference about that night, and that was, I was almost never allowed to have control of the cocktail shaker because I make drinks two or three times as strong as they need to be. But I think Drew could see that he didn’t want to fight with me that night, so he relinquished control of the cocktail shaker and just grimaced at me from across the room while he was sipping his drink.

When it came time to choose where to go for the night, we went to one of our safe spaces, a place that we’d been to hundreds of times before. Everything about Pulse nightclub was normal that night. There was a line outside, the same drag queen who was always there at the front door was there and snatched my money out of my hand. We went to the same bartender we always went to. We ordered the same drinks we always ordered. We went to the same spot on the patio where we always stood. Drew had a master’s degree in clinical psychology. And when he’d had a sip or two of his cocktail, he would start giving you free therapy sessions, whether you wanted one or not.

That night, Drew was on a rant about love and compassion, and he was saying, “I never understand why we let the little things get in the way of how much we care about each other.” He wondered aloud why people stay so focused on what makes us different instead of focusing on what makes us so similar. He had these long, dangly arms, and when he was coming in for a landing on his point, he would drape one over your shoulder. And he draped an arm over my shoulder and said, “You know, what I wish we did more often is tell each other that we love each other.”

It was not long after that when the most normal night of my life, in one of the safest spaces I knew, became the extraordinary tragedy that everyone knows it to be.

I was washing my hands at a bathroom sink just after two o’clock in the morning. I can remember the bright, painted faces of drag queens on a poster above the urinal, some promo for an upcoming show. I can remember a cup sitting on the edge of the sink, sort of half full of its contents, looking like it might fall off. I can remember how cold the water was from the faucet. And I distinctly remember the first sound of gunshots.

I remember the hair standing up on the back of my neck. There was a group of people, about a dozen people that rushed through the hallway and into the bathroom. The looks on their faces — like they had seen the purest form of evil. I remember huddling with them against the wall, the girl behind me shaking so violently trying to control herself from screaming so we wouldn’t be found, that I could feel her vibrating against the tile floor underneath us. I remember the smell of blood and smoke that started to waft in the room and this debate about whether or not we should run or hide.

We were in a men’s-only restroom, which meant that there were no stalls. There were no doors. There was no hiding. There was just us, a short hallway, and then the bar from which the gunshots were emanating. And so we made a break for it. I remember locking arms with these dozen people moving quickly down the hallway. I remember the fog machine smoke was continuing to billow, and so the room was foggy.

I remember the relentless bang, bang, bang of gunfire in the background that felt like it was exploding through my chest. I remember the sliver of light in the back of the room from this door that I didn’t even know existed before then. I remember wondering why I never got a chance to say goodbye to my parents because I was pretty certain that I was going to die.

And then I remember feeling relief as the door flung open. We were standing in a parking lot, there was still this rage of gunfire in the background. There were people screaming and jumping over bushes, but there was a sense of relief because we had done the impossible — we’d made it out of this situation. I also remember how fleeting that sense of relief was when I realized that my best friends, the people who changed my life for the better, had been standing underneath the disco ball, wrapped in each other’s arms, right in the line of fire of the shooter.

MW: When did you finally hear that Drew and Juan had passed?

WOLF: I dialed Drew’s phone for what must have been a thousand times, every time telling myself that maybe he was in a hospital bed somewhere, maybe he was in surgery. Maybe he dropped his phone in the club, trying to convince myself that there was a chance that Drew had made it. We sat in my living room for some time, a group of us, and would keep track on a napkin of how many people had been identified versus how many were left. We kept asking ourselves whether or not there was a chance that maybe our best friends had made it.

We first learned about Juan when someone else who’d been at the club that night called me, and said that he saw Juan. I asked him if he was okay, if he was alive, and he said, “I don’t know, I didn’t get a chance to talk to him. I just know they were loading him into an ambulance.”

I got ahold of Juan’s family and let them know that their son had been shot in the club. They called later on that morning to inform us that he had never made it to the hospital. He died in the ambulance. It was in that moment that I understood for the first time in my life that heartbreak is not a cliché. I thought the pain of losing someone in such a violent and sudden way might actually kill me. There was a fracturing that happened inside my being. I didn’t really know what to do with that, in that first moment. I sat outside for a long time, just staring at the pavement, trying to wrap my head around what had just happened.

We didn’t learn about Drew’s death until the next day. His mom had been waiting for news. She was growing increasingly frustrated with how long it was taking for them to share information, especially because by Monday morning, we knew that everybody had been identified.

So she was taken to a side room where an FBI agent and a police officer sat her down and said, “Ma’am, your son is dead. He never made it off the dance floor.” And that was it. After all of the fight to find a place to belong in the world, after all of the struggle to find safety, after finding that belonging and safety in chosen family like Drew and Juan, in an instant, with a pair of phone calls, they were gone.

MW: After the Pulse shooting, you became active in the gun reform movement. With the recent passage of the gun bill in Congress, how do you feel about the progress of that movement?

WOLF: There are two things that can be true at the same time. The first is that we have made remarkable progress. I start by acknowledging that — because that progress is built on the stories and lived experiences of people who’ve been impacted by gun violence. There is a courage and selflessness that it takes, especially for people who buried their children, to share such a heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, traumatic moment in your life, knowing that it may result in no change, but that you’re simply adding a building block to something that we’re working on together.

Think about the 2016 election cycle. After Pulse happened, there was a movement to pass new gun safety legislation led by Congressman John Lewis. There were sit-ins in Congress. There was a push for a “no-fly, no buy” rule. There was another push for an assault weapons ban, but political strategists would tell people like Secretary Clinton and others, “You can’t run on banning assault weapons. You just can’t do it. If you make that the cornerstone of your campaign, if you put that in your platform and you run on that, you’ll lose. You have to find this sort of moderate, medium ground to run on.”

And then in 2018, we saw a sort of seismic shift in the other direction, but it didn’t happen in two years. It came about from decades’ worth of organizing and mobilizing from community members, survivors, family members, first responders, and healthcare professionals. And after years and years of organizing and coalition building and applying pressure, Moms Demand Action outspent the NRA in that midterm election cycle, and forty NRA-backed candidates for Congress were defeated.

It was one of the first times where collectively we said, “You can run saying you want to change the gun laws, and that is a plus for us, not a minus. In fact, you may get people to show up because that is the issue they’re voting about.” Flash forward to 2020, and you have a presidential candidate in Joe Biden who is able to run on the most progressive gun safety platform in decades because of the work that organizers and community members had been doing.

It’s also true that what has gotten over the finish line in the last few weeks is woefully insufficient. It’s not even close to what we need. It doesn’t fundamentally address our “Swiss cheese” approach to background checks. It doesn’t fundamentally address a national extreme-risk protection order, a red-flag law. It doesn’t fundamentally close a number of loopholes that exist.

It does some work, and it signals that we are beginning to break the log jam, but make no mistake, this milquetoast approach has been bought and paid for by the gun lobby and gun manufacturers, who are very powerful, very wealthy, and have spent a lot of money to gridlock Congress on this issue. They’re getting exactly what they paid for, and it’s going to take a lot longer than a two-year, four-year, or even 10-year cycle for us to break that gridlock. But I think we can acknowledge the progress that’s been made and we can also understand that we have a lot further to go.

MW: In the wake of the Pulse shooting, even Donald Trump tried to wrap himself in the flag of “defending” gays from radical Islam —

WOLF: Give me a break. Lot of good he did with that.

MW: Nonetheless, it was “en vogue,” even among Republicans, to cast themselves as defending the LGBTQ community, or at least cisgender gay men. Yet six years later, politicians seem much more hostile to the LGBTQ community and more willing to pass laws targeting the community. How have you seen that shift play out in Florida?

WOLF: Well, let me start by saying this: Everyone should be very wary of those who leap to allyship, but don’t carry any receipts of the work they’ve done to be present with the community. Politicians are very good at showing up to places they’ve never been to before, just in time to try to win an election cycle.

What we really need in our leaders, what we really need in our allies are people who have shown us a willingness to grow, to be uncomfortable, to learn with us, and to put their privilege on the line. Not one of those politicians, including Donald Trump, who suddenly became the world’s self-proclaimed “greatest LGBT ally,” had previously been willing to put their privilege on the line or to get uncomfortable in defense of LGBTQ lives. So let’s start there.

I am not naive. And I don’t think our community, in general, is naive. I was in high school in 2004 when George Bush was running for re-election. And he built that re-election effort in part by trying to weaponize same-sex marriage, parading around the country, working to ban same-sex marriage by constitutional amendment. My home state of Oregon passed a constitutional amendment ban on same-sex marriage that year. And I remember what that political climate felt like. I told you about the protests at my school, about the signs outside, parents waving them in our faces that said, “It’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.” I know what vitriol and hate feels like and I also know that it didn’t just disappear.

There was a moment in 2015 where I think LGBTQ people rightly breathed a sigh of relief, where they exhaled for the first time in decades because we’d scored a number of wins. We got marriage equality over the finish line via a Supreme Court ruling. The White House was lit up in rainbow colors. Social progress had been made. LGBTQ people were suddenly making their way into media representation. It felt like we were beginning to crack the code on inclusion and acceptance of LGBTQ people. But we also understood that opponents to equality weren’t sleeping, they hadn’t said “good game,” patted us on the back and moved onto a new community to terrorize. They were plotting. They were in their focus groups. They were in their think tanks asking the question of how to begin to peel back the civil rights that LGBTQ people had won.

While I don’t know if this is true for our allies, I know for a fact that for LGBTQ people, Pulse was a reminder of what’s at stake. Pulse was a reminder of the work that was left to do. It was a reminder of the cost of hate and militarized hatred. So in some ways, the regression we’ve seen on issues of LGBTQ civil rights in the state of Florida is not surprising. It’s a predictable backlash to the progress that we as a community have made. That backlash is violent. It is hostile. It is dangerous, but it is predictable.

What we’re seeing in the state of Florida is a disturbing symptom of a growing threat of extremism. And it is in large part aimed at the most vulnerable people in society.

The blueprint from right-wing extremists is very clear. If they can isolate transgender people, if they can turn them into a political lightning rod, if they shift our perception of transgender people from human beings to shadow-ism that needs to be defeated, then they can justify anything they do to them. They can kick them off of middle school soccer fields. They can toss them from bathrooms. They can strip them of their health care. They can pull books about them off of shelves, censor yearbook pages about them. They can rationalize open discrimination, bigotry, and ultimately violence against them. They can dehumanize a population of people that desperately need our support.

That is the blueprint right now. It didn’t come out of nowhere. It was birthed from this backlash that was always coming because we have done the hard work of getting this society to accept that we exist, that we are of value, and that we deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

MW: It seems that people are increasingly becoming more “triggered” by gender-nonconformity or gender-fluidity, even though that concept has existed among subsets of the straight community for decades, whether that’s skaters, goths, hipsters, and other groups. Clearly, there’s always been a subset of the population that harbors hostility to gender-nonconformity in whatever form it takes. But why do you think that hostility appears to be more out in the open, more vocal, and more violent in recent years?

WOLF: I’m glad that you named it because, let’s be clear, that gives the game away. These systems of oppression, when we name them, when they’re so visible like this, they suddenly become very easy to see. The patriarchy and white supremacy that forces us into these little tiny boxes are always damaging to everyone.

As you said, heterosexual cisgender men also suffer at the hands of the rigid gender binary that tells us how to cut our hair and what colors we like painted on our baby rooms and whether or not we use the Degree deodorant with the male packaging versus the female packaging. These are structures that are designed to chisel away at people and force them into conformity in service to a greater power structure. And the idea that people can break out of that structure, that they can be individual, that they can wear whatever they want or identify as they identify, anytime it breaks outside of that rigid conformity, is viewed as a threat.

As a society, we have been indoctrinated to believe that that threat must be contained or eliminated, so we turn on one another, instead of asking really tough questions about the rigid structure that got us there in the first place.

So your question was, “Why is it so out in the open right now?” And I think the answer is twofold. Number one, it’s hard, if not impossible, for us to unwind the way in which that system of oppression, that gender conformity structure, is so ingrained in who we are. And so there is a fear — we heard it expressed in this year’s legislative session in Florida — that because Gen Z and younger don’t feel as confined to that gender binary as previous generations did, because they are comfortable simply being themselves, that [gender-nonconformity] is viewed as a threat by people who don’t understand it.

The second thing I would say is that those people who are now openly bigoted or openly discriminatory, they’re saying the “quiet” part out loud about drag queens, about trans people, about everyone.

Those people have been emboldened and empowered by the dehumanizing language our powerful leaders use to try to win elections. So those leaders feel that fear of the unknown, fear of something they don’t understand, they weaponize it, they use dehumanizing language to turn the volume up on it to 100, and in doing so, they enable and empower the most violent and dangerous extremists among that population.

I’ll give you a very clear example. In Florida in January, lawmakers proposed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. From the very beginning, the community named it that, because while the bill didn’t have the word gay or lesbian or trans or bi in it, we knew that it was aimed directly at LGBTQ people, that it was designed to erase us. And that nickname absolutely outraged the right-wing. “How dare you call the bill something that we didn’t name it?” And so we went through the legislative process and the bill was mired in this debate over whether or not it’s appropriate to erase LGBTQ people.

The bill was floundering, quite frankly, and the governor realized that his bill was stalling. He desperately needed it to get over the finish line to bolster his resumé. So he hit the nuclear option. He sent his press secretary to Twitter to traffic in some of the most disgusting and vile smears used against our community throughout time.

She called us “groomers.” She insinuated that, by existing, LGBTQ people are a threat to children, and that we are complicit in pedophilia if we suggest out loud that LGBTQ people deserve to be visible in the world. That language was then picked up by every right-wing outlet on the planet. Fox News started saying it, Newsmax started saying it, Ben Shapiro, and Candace Owens.

And all of a sudden those same words, groomers and otherwise, began showing up on posters outside of Disney at protests, in the hands of Proud Boys outside of bars in Dallas, Texas, and in communication threads with right-wing extremists who are threatening mass violence against a Pride [celebration] in Idaho. That is the way in which the dehumanizing and hostile rhetoric of powerful people enables and empowers violent extremists to say the “quiet” part out loud.

MW: Given the increasing popularity of the “groomer” label, which is based on homophobic tropes dating back to the ’70s with Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, and the talks of purging gay and lesbian teachers, which echo the failed Briggs Initiative of 1978, doesn’t it seem like anti-LGBTQ forces have successfully revived this language to demonize the LGBTQ community?

WOLF: Let’s start by acknowledging that the public still largely supports LGBTQ people. In the state of Florida, if you look at the polling, it’s something like 67 percent of Floridians support full nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people.

What is potentially different, in this instance, is the way that politicians like Governor DeSantis and others have been able to manipulate language to prey on those fears that people have without coming out or visibility. We’ve seen some data that tells us, interestingly, that people who support the “Don’t Say Gay” bill can agree with the LGBTQ community’s perspective and the bill proponents’ perspective at the same time. They don’t necessarily see them as in conflict with one another. So that’s one part of it: that right-wing think tanks have created legislation that exists on confirmation bias. It toes that line and they’re able to use coded language when they’re talking about the legislation that makes it seem “reasonable” or understandable.

But in terms of the language that they’re using, I think the reason that we’ve seen a surge in this openly bigoted and hateful rhetoric is the impact of Donald Trump, and the fact that politicians like Donald Trump can say the most outrageous, extreme, egregious things and face absolutely no accountability for it, and instead be endeared to this supercharged extremist base.

For politicians like DeSantis, who want to run for president in 2024, it’s a cost-benefit analysis at all times: “What can I get away with that earns me the support I need to get to the next political destination?” It’s not about helping people. It’s not about protecting children. It’s not about doing their jobs, it’s about winning elections.

They have made a calculation, and thus far have been successful in saying, “if we pass this coded legislation that makes people feel empowered and takes on these shadow-isms that they’re afraid of, but can’t really name, and we use this supercharged language with our extremist base, we’re going to face no political accountability for it, and instead we’ll probably shore up the base votes we need to win the next election cycle.”

Until we can break that pattern, they will continue to do it. Until we can force them to face political accountability for their actions and their words, they will continue to do it.

It’s happened a number of times before in our history, when we’ve dehumanized people, when we’ve turned whole communities into boogeymen. What it has taken to break that cycle has been political accountability. These politicians have to lose their jobs for being bigots out loud. The day that happens, you will see a change, but until then, they don’t see any reason to try anything different or tone it down because they’re getting exactly what they’re hoping for.

MW: One of the political tactics we’ve seen used by proponents of the “Don’t Say Gay” movement is using representatives from the gay community to defend the law and other LGBTQ legislation. How do you respond to people purporting to speak on behalf of the community who are gaslighting the rest of us?

WOLF: Well, there are always going to be people who cozy up to power and are willing to do whatever it takes to cozy up to power. They are incredibly privileged and are not willing to put that privilege on the line to be true allies and accomplices to people in other marginalized communities. But I will say this: I keynoted a speech at New York City Pride last weekend. And what I said to this group was, “To those in the LGBT community specifically, who have told yourselves that if I just sell out the rest of the acronym, if I just jettison other people in this movement, or have convinced yourselves that their struggle is not your struggle. Shame on you. Shame on you for being so shortsighted, for being unable to see how the stripping of civil liberties for one community means the stripping of civil liberties for all communities.”

There is no way around the fact that we are in this together. Take the Dobbs v. Jackson decision. The elimination of Roe v. Wade protections, the right to privacy, was never just about someone’s right to an abortion — it was always about sexual autonomy, which has a whole host of ramifications. And so the Dobbs v. Jackson case comes out, Clarence Thomas writes his concurring opinion where he basically says, “Looks like it’s time to revisit same-sex marriage and the criminalization of homosexuality and contraception while we’re at it.” And people suddenly begin to put the pieces together.

Our fates as members of the community have always been tied together, and so, while there are always going to be “useful idiots” who are quick to latch onto whatever talking points they’re fed so that they can see their names trend on Twitter, or they can in the short-term, build a platform for their Substack or whatever, the truth is that our liberation has always been linked, that our civil liberties have always been linked, and we cannot get where we’re going if we are pitted against one another. It’s really going to take all of us if we’re going to see true freedom and liberty in this country. And it’s my hope that people stay grounded and understand that, especially at this moment.

MW: In terms of the “Don’t Say Gay” law specifically, we’ve seen a number of youth get involved in activism around the law, sometimes even suffering penalties for organizing “walkouts,” such as having their graduation speech censored, being told they couldn’t run for student body president, or being moved from a history class for a presentation on Stonewall. What do you take away from the activism and engagement of LGBTQ youth around this issue?

WOLF: Diamonds are formed under pressure. So often, the moments when hope has been ignited, when progress has been birthed, have been in the greatest times of struggle. First and foremost, these young people should not have to be fighting for their lives. They should not have to be fighting for their humanity, for basic dignity and respect. They should not be fighting against people who want to erase them from yearbooks or graduation stages or even classrooms altogether. They should be able to be kids. They should be able to go to school, to learn math and reading and science and not be harassed by politicians who are desperate to get a new pin on their lapel. But that is unfortunately where we are.

We are in a situation where young people are having to advocate for the world that they want to live in because they ultimately are the ones who get to live with the ramifications of these political debates we’re having right now. They have to live with what happens next.

And they are saying unequivocally that this is not the world they want to be a part of, that they have a vision for something better, something more inclusive, a world where justice and equality actually mean something. And as a result, they have begun to mobilize.

I am always incredibly inspired by the passion and strength of young people in our society. They have untapped vision and imagination. They have bountiful energy where they can plug in all the time. And again, they have a serious stake in the game. For them, it is their future. It’s what kind of world they want to be a part of in college and when they start a family and what they want their kids and their grandkids to grow up understanding.

These young people have already changed the world. They will continue to change the world. They give me hope, and I know that they give so many other people hope. I want them to know that they have allies and accomplices all over, that I am always going to show up to fight for them, because I think they’re worth fighting for, that I’m always going to show up to elevate their stories and help share their lived experiences, because those stories are worth telling. As long as they need us to continue to help in the fight, we’re always going to be there for them.

MW: What would be your advice to people in the LGBTQ community or people who are trying to push back against these attacks on the community?

WOLF: The first piece of advice is to take care of yourself, because as you mentioned, this is a marathon, not a sprint. I know that’s a cliché, but it’s the truth. Things are likely to get worse before they get better. And I think people should just understand and acknowledge that we are in a perilous time, that things are incredibly dangerous for marginalized communities, especially LGBTQ people. And so, what do I mean by taking care of yourself? Well, Audre Lorde has my favorite quote, when she says that “self-care is not selfish, it’s an act of self-preservation.”

That in itself is an act of political warfare, that your resistant and defiant assertion that your life matters, that you matter in a system that tells you that you’re only as valuable as what you can produce, how many hours you can work a day, how much money you have, and what kind of car you drive. You are asserting that you’re going to take the time and space you need to be whole is an act of political resistance. So do not feel like everything will fall apart if you have to take a moment for yourself to recharge. Lean on your community members, take care of yourself, because we’re in it for the long haul.

The second thing I would say is to get comfortable being uncomfortable. This moment requires us to dig deep and pull from some of our roots that maybe are rusty. We are obligated to be civically engaged in ways that we maybe haven’t been in a while. Some people maybe haven’t been engaged ever before. Being a part of a democratic system doesn’t mean that you are a participant on election day and a spectator for the rest of the year. It requires you to be there all the time. You have to be at local government meetings. You have to protest, you have to petition. You have to rally and march. You have to sometimes go on strike. You have to do all the things that are part of being in a democratic society. It requires our engagement all the time. And that system is on life support right now. My boss, Nadine Smith, always says that apathy is an ally to the status quo. Choosing to disengage now is not an option.

The final piece of advice that I would give people is to be more authentic and audacious than you ever have been. Part of the goal of right-wing extremists right now is to scare us into the closet. They want us to be afraid to be ourselves. They want us to tone it down, to fit in that box, to get back in line. And those moments call for us to be even more proud and audacious and authentic than we have been. Think about all the progress we’ve made as a community.

We didn’t make progress on LGBTQ civil rights because the politicians somewhere changed an “and” to an “or” on a page. We have made that progress when we’ve told our stories. We fought for and won the right to marry the person we love because we were unashamed of who we are. We stood on capital steps, on courthouse steps, held hands and said, “Our love is love and it deserves to be seen.”

We fought back during the HIV and AIDS crisis — when everyone seemingly had turned their backs on us — and redefined what it meant to be someone living with HIV. We showed our faces. We extended a hand to people like Princess Diana. We humanized who we are: we’re your family members, we’re your neighbors, we’re your friends, and we deserve to be treated with that same humanity.

So throughout history, it’s our stories that have propelled progress. In this moment, we are challenged to share our stories more audaciously, more authentically, more courageously than we ever have been. And to lift up one another’s stories in the process.

Follow Brandon Wolf on Twitter at @bjoewolf and on Instagram at @brandonjwolf.

Learn more about Equality Florida at www.eqfl.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.