‘Turandot’ is Almost, But Not Quite, Fabulous (Review)

The Washington National Opera's "Turandot" creates a new ending for the Puccini masterwork, but the production feels lacking.

The headlines about the Washington National Opera’s Turandot may be the premiere of a new ending, but it still has to be about the 95% that comes before the big reveal.

And despite capturing Puccini’s hauntingly grand motifs and some choral spectacles akin to standing behind the engines of an Airbus A30, this production is only almost, but not quite, fabulous. There is design, color, movement, and moments of aural loveliness under the rock-steady hand of director Francesca Zambello, but somehow it all lacks a certain je ne sais quoi.

Wilson Chin’s sets may be a satisfyingly intricate pipework-like creation made striking when washed in the saturated colors of Amith Chandrashaker’s lighting, but the moon — offered hugely in S. Katy Tucker’s projection — feels flat when it needs splendor. Although the soldier dancers are sprightly and fill the space with darting movement, they lack a certain precision, diluting the sense that this land is ruled by an iron hand.

And then there is the choice to offer a peasant-chorus clothed in beige and overtly multicultural. It may be intended to reflect the many people passing through this ancient Beijing, but the message feels too self-consciously modern and too bland for the power of their vocal presence. It just all feels a little too safe, a little too devoid of personality, especially for a director capable of a Ring Cycle of such impressive vision.

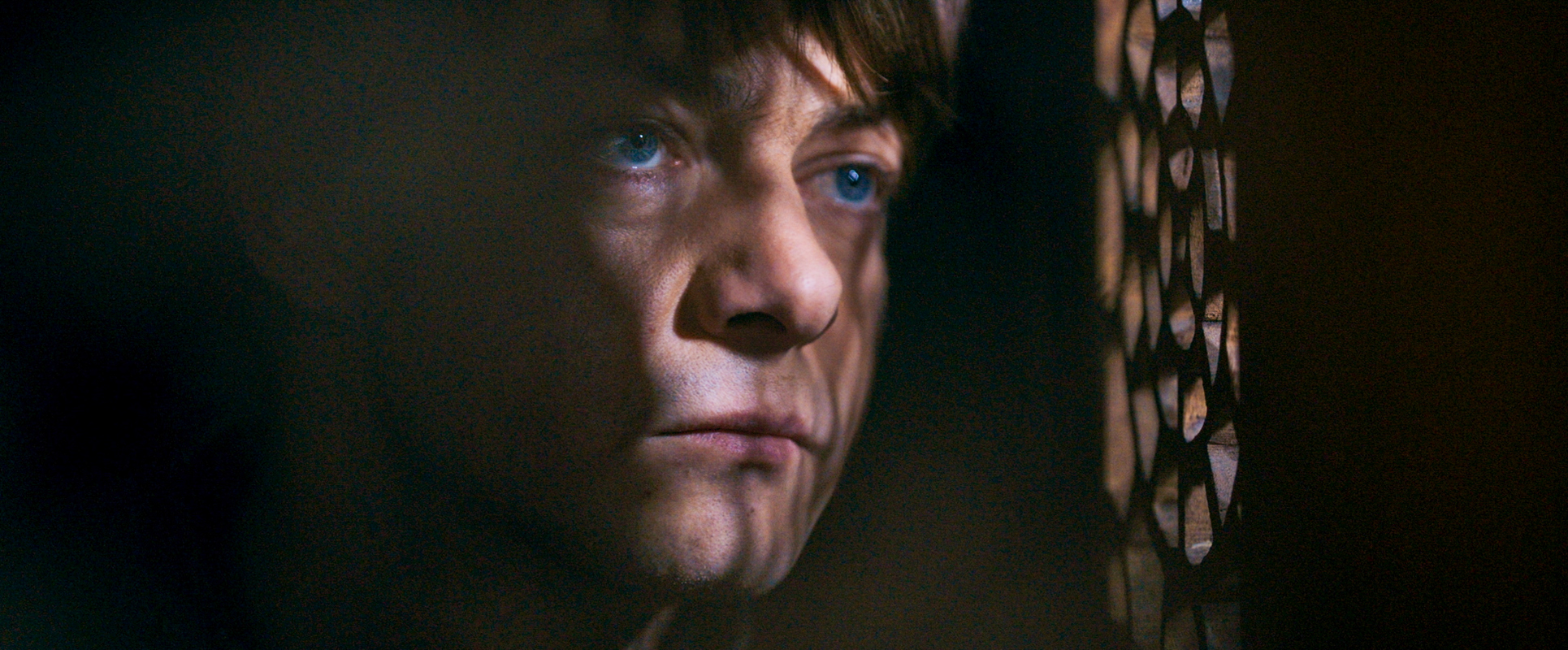

The unevenness continues with the lovers at the heart of the tale. Tenor Yonghoon Lee’s Calaf, the lovelorn prince who will overcome Turandot’s resistance to any and all suitors, offers too light a dramatic presence, never quite projecting the instant ardor-from-afar or co-carrying the catharsis of the new ending. This lack of nobility of intent isn’t in any way helped by a costume that has him looking more like an Orvis catalog model than a prince in mufti. If Lee’s voice is capable of cutting a dramatic swath through the orchestra, it’s with an edge that is a tad too harsh and lower notes that all but disappear.

As Turandot, the princess who has dispatched so many princes through her deadly riddles, Ewa Plonka is suitably stately and knows her way around some grand costuming, but she is brittle. The new ending may provide an enhanced explanation and resolution to her story, but this Turandot never convincingly thaws — it’s simply too hard to believe she’s capable of change, especially for this Calaf. That said, Plonka offers a glorious, full-bodied soprano, even if she never quite woos the ear or the heart.

Indeed, the most extraordinary performance of the night, and far more a reason to see this new production, is Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha’s Liu, the servant who will sacrifice all to keep secret Calaf’s name. Rangwanasha is wholly convincing, bringing a quietly powerful sense of her unrequited love and the grief of her final moments. In keeping with Liu’s gentle soul, Rangwanasha sings with a beautiful velvety softness that evokes her infinite sadness. These moments — and the several glorious chorus-driven crescendos — are where the production really feels like the Puccini you’ve come to hear.

Other standouts are the clever rendering of the three dapper bureaucrats in their 20th-century office. Ethan Vincent is an especially strong Chancellor, while Jonathan Pierce Rhodes as Head Chef is a tenor to watch. As Timur, Calaf’s father, Peixin Chen is eminently believable in this pairing with Rangwanasha’s Liu, and he offers a gorgeously mournful bass.

As for the new ending: as an artistic exercise, librettist Susan Soon He Stanton and composer Christopher Tin certainly bring some exciting talent to re-imagining a finale that Puccini died before he could finish. But, in truth, the new libretto somewhat gilds the lily. Classical opera routinely depends on a devotion to the importance of family, tradition, and ancestors; enhancing Turandot’s personal backstory doesn’t feel necessary.

It also raises a new problem: with such a fresh trauma in her past, it makes it even less likely that this woman will be ready to trust. Stanton’s other big change — replacing Calaf’s game-changing kiss with something more heartfelt ends up feeling belabored. It’s also somewhat ironic: the man’s kiss may have been banished but it’s still a man who is talking her out of her long-held principles. Why not have her stand alone and talk herself into a new way to lead her city, which includes making herself happy?

Of course, the challenge of adding twenty minutes to this classic is how to add a musical addendum to the work of one of the greatest-ever opera composers. Tin is wise not to mimic the master and he does an interesting job of rearranging motifs and building a new kind of musical finale. Whether this new ending to the story and its musical accompaniment will stick will likely depend on what other interpretations emerge now that the copyright on Turandot has expired.

One thing is for sure: Turandot will always be one of the most singular women in opera history. When fully actualized, she is always a force that surpasses a kiss or a conversation.

Turandot (★★★☆☆) runs through May 25 in the Kennedy Center Opera House. Tickets are $45 to $299. Call 202-467-4600 or visit www.kennedy-center.org/wno.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.