‘Disclaimer’ is Pulpy Suspense With an Arthouse Sheen

Alfonso Cuarón’s gripping "Disclaimer" pits Cate Blanchett against Kevin Kline in a thriller of long-held secrets exposed to light.

By André Hereford on October 20, 2024 @here4andre

Arguably the most pivotal character in Alfonso Cuarón’s Disclaimer doesn’t appear onscreen until episode two: Lesley Manville’s tremendous Nancy Brigstocke, who’s already dead.

By the time Mrs. Brigstocke quietly, though not timidly, enters the picture, chapter one has deftly positioned the series’ two Oscar-toting main combatants. Cate Blanchett enthralls as TV journalist and documentarian Catherine Ravenscroft, described by no less than Christiane Amanpour as “a beacon of truth,” while the newswoman bestows what is presumably not Catherine’s first prestigious prize for excellence in journalism.

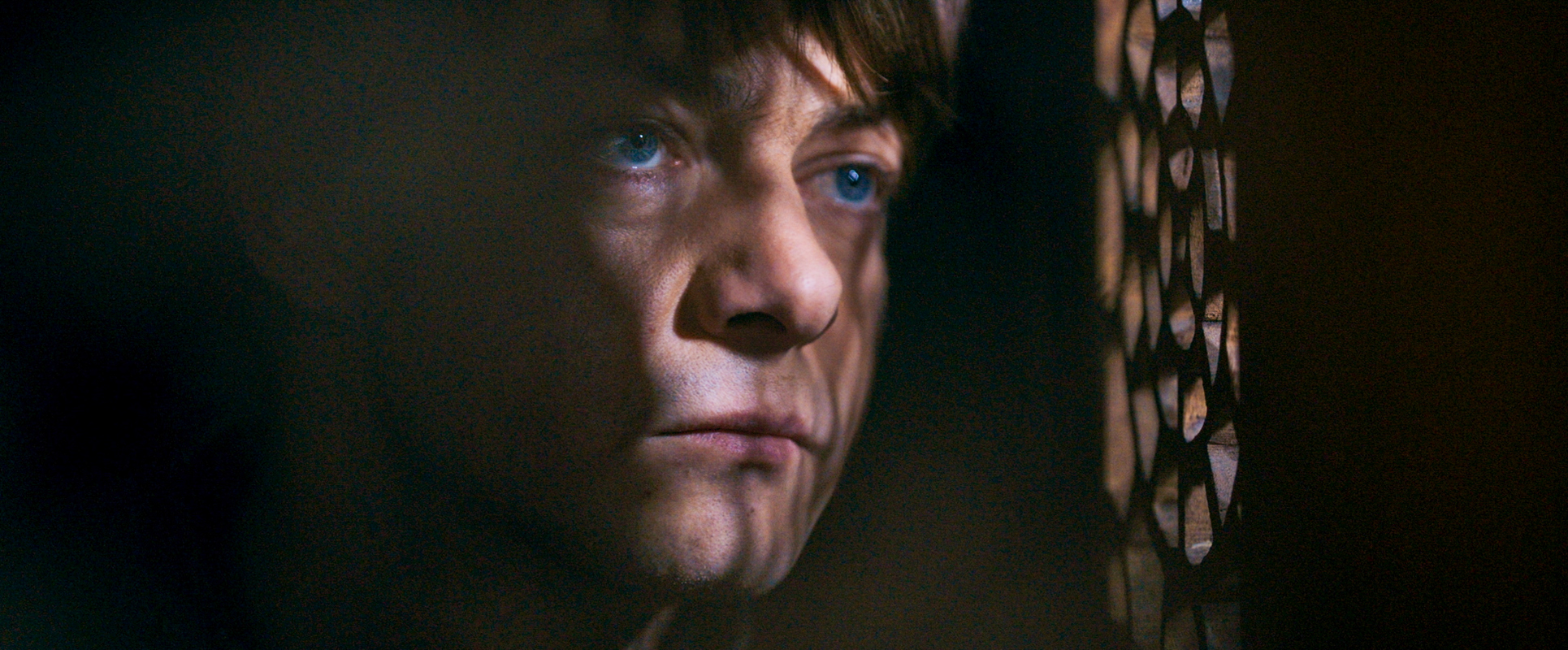

Living in a vastly different universe of professional regard, and physical comfort elsewhere in London, Kevin Kline is modest, though not exactly humble, boys’ school professor Stephen Brigstocke. Stephen is Nancy’s widower, a lonely man who seems to have lost his greatest love.

On top of his grief, nakedly portrayed by Kline, Stephen learns of a secret Nancy kept that ignites his mouth-watering quest for revenge against Catherine. Kline renders Stephen’s bitterness with complexity, as Disclaimer, based on Renée Knight’s 2015 novel, weaves Nancy’s secrets, and Catherine’s, and Stephen’s into a juicy all-out battle between Catherine and Stephen. He’s determined to bring her down by dredging up her past.

Written and directed by five-time Oscar-winner Cuarón, the series’ seven chapters maneuver smoothly between the Ravenscrofts — Catherine and her rich nincompoop husband Robert, played to frustrating perfection by Sacha Baron Cohen — and the Brigstockes, Nancy, Stephen, and their 19-year old son Jonathan (Louis Partridge).

Jonathan is also a ghost in this drama, which unfolds like a cliffhanger serial, complete with silent-film fadeouts. It’s pulpy suspense with an arthouse sheen, pristine production design, an awards-heavy cast, and novelistic structure.

Stephen narrates his side of the story in voiceover, while we hear Catherine’s point-of-view elegantly narrated in second-person voiceover by Indira Varma. Varma also voices omniscient narration peering shrewdly into each character, including Catherine and Robert’s surly 25-year-old son Nicholas, played by Kodi Smit-McPhee.

McPhee puts the proper measure of petulance into Nicholas’ scenes with his parents, who have recently pushed him into getting his own place. For Catherine, who feels she’s been a “terrible” mother, her son’s angst over moving out is yet another source of sinking guilt.

Also, reflecting the show’s astute parent-kid dynamics, it’s yet another scenario where Robert blithely allows Catherine to be branded the bad guy. But that’s a light burden of blame compared to the devastating accountability she fears after she receives a package in the mail, a slim paperback novel titled Perfect Stranger. The book comes with a strange disclaimer: Any resemblance to persons living or dead is not a coincidence.

Indeed, Catherine recognizes herself in Perfect Stranger, set 20 years past, depicting her fateful encounter, while on vacation in Italy, with 19-year-old Jonathan Brigstocke, who was traveling alone. Whatever happened between the pair back then, Stephen and Nancy Brigstocke later demand accountability from Catherine in the most punishing terms.

In dramatizing the Brigstockes’ nefarious means, the series still regards them, as well as Catherine and Robert, with a compassion for parents longing to connect with their kids. Their mutual sense of loyalty and responsibility to their sons isn’t misguided, though their methods may be.

Any one of them might also be misinformed, even by their own memory. We are our own most unreliable narrators, the show implies, telling and retelling the stories of our lives with more sentiment than accuracy. Shuttling back and forth in the chronology of events, Disclaimer tests more than one version of the truth.

Giving visual distinction to the crisp, de-saturated sumptuousness of the Ravenscroft’s pad, versus the sun-bleached shores of Italy, and the dour environs of the Brigstocke home, Cuarón assembled the couldn’t-be-more-A-list tag-team of cinematographers Emmanuel Lubezki (Gravity) and Bruno Delbonnel (The Tragedy of Macbeth), who traded off on shooting the show’s multiple locations and myriad perspectives.

Finneas O’Connell’s languid score, used sparingly but effectively, adds to the textured sound design. In one witty instant, we hear the sound of someone covering a cockroach with a glass, but from inside the glass, i.e., the perspective of the trapped victim. That’s where Stephen wants Catherine, trapped under glass.

The series stashes its humor in such slight but sharp gestures and not-quite throwaway dialogue, like Catherine mentioning that they’ve recently downsized to this still-enormous London townhouse. Blanchett serves the deadpan humor, and every other layer to the character, beautifully, sharing the storyline with Leila George as young Catherine.

Arguably the other most pivotal part, young Catherine, in her every word and action, is held up to the scrutiny of multiple lenses judging what kind of woman she is, what kind of mother she is, and whether her actions with Jonathan earn the retribution Catherine faces 20 years later.

Catherine’s present-day public humiliation, when it arrives, is depicted a bit clumsily, but Disclaimer nails her panic as she sees her darkest secret being weaponized against her, and her tenacity when she decides to fight back to protect her world from destruction.

New episodes of Disclaimer (★★★★☆) stream every Friday on Apple TV+. Visit www.apple.com/apple-tv-plus.

‘Black Bag’ is a Slam-Bang Thriller from Steven Soderbergh

Steven Soderbergh's spicy spy thriller "Black Bag" comes packed with sharp twists, intrigue, and innuendo.

By André Hereford on March 16, 2025 @here4andre

Most A-list filmmakers in the streaming era would be glad, and lucky, to have one decent feature hit theaters in a year. So, snaps up to Steven Soderbergh, back with his second slam-bang film this season, following up January's nifty haunted house thriller Presence with the wily spy thriller Black Bag.

Soderbergh and Presence screenwriter David Koepp load up the sex, lies, and video files for this taut tale of a search for the snake hiding within a nest of secret agents. The top agent, George Woodhouse, portrayed with cool determination by Michael Fassbender, is tasked with rooting out a mole embedded in a black-ops division of British intelligence. Among his list of suspects is his own wife, Kathryn, played with a sly glint in her eye by a brashly brunette Cate Blanchett.

Gay French Thriller ‘Misericordia’ is Creepy and Suspenseful

Alain Guiraudie's queer thriller "Misericordia" subverts its simple domestic setup with secrets, lies, and hidden desire.

By André Hereford on April 13, 2025 @here4andre

Serene on the surface, seething with desire beneath, Alain Guiraudie's French thriller Misericordia is fascinatingly strange, creepy, and suspenseful.

Much as the filmmaker's masterful 2013 thriller Stranger by the Lake planted a sinister seed by setting a serial killer loose in a tranquil outdoor gay cruising spot, here Guiraudie upends a seemingly wholesome homecoming in the countryside with dark undercurrents of sex and violence.

Although, beyond a couple of pointed shots of male nudity and one shot of bleeding, there's little sex or violence onscreen. Merely the potential for the former and the threat of the latter linger equally over nearly every scene in this odd chamber piece set in a remote village tucked amid the forested hills of Occitanie in Southern France.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

The Magazine

-

Most Popular

Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration

Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration  Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal

Gay Army Reserve Officer in Uniform Sex Video Scandal  Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'

Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'  Ex-Mormon Josiah Ryan Spreads Love as 'Gay Jesus' in Utah

Ex-Mormon Josiah Ryan Spreads Love as 'Gay Jesus' in Utah  Gallery: Blake Little's Breathtaking 'Construction Nudes'

Gallery: Blake Little's Breathtaking 'Construction Nudes'  A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'

A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'  'The Wedding Banquet' Remake Serves Laughter and Love

'The Wedding Banquet' Remake Serves Laughter and Love  Holly Twyford and Kate Eastwood Norris Shine in 'Bad Books'

Holly Twyford and Kate Eastwood Norris Shine in 'Bad Books'  MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates

MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates  'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches

'Gray Pride' Protests Hungary's Ban on Gay Pride Marches

Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'

Hugh Bonneville Talks 'Downton Abbey,' 'Paddington,' and 'Vanya'  Holly Twyford and Kate Eastwood Norris Shine in 'Bad Books'

Holly Twyford and Kate Eastwood Norris Shine in 'Bad Books'  'The Wedding Banquet' Remake Serves Laughter and Love

'The Wedding Banquet' Remake Serves Laughter and Love  Ex-Mormon Josiah Ryan Spreads Love as 'Gay Jesus' in Utah

Ex-Mormon Josiah Ryan Spreads Love as 'Gay Jesus' in Utah  Gallery: Blake Little's Breathtaking 'Construction Nudes'

Gallery: Blake Little's Breathtaking 'Construction Nudes'  Becca Balint: The Pride of Vermont

Becca Balint: The Pride of Vermont  Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration

Signature Honors Mandy Patinkin in Emotional Celebration  MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates

MISTR's Free DoxyPEP Leads to Huge Drop in STI Rates  A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'

A Potent (and Pricey) 'Good Night, And Good Luck'  Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'

Sarah Snook is Astonishing in Broadway's 'Dorian Gray'

Scene

Metro Weekly

Washington's LGBTQ Magazine

P.O. Box 11559

Washington, DC 20008 (202) 638-6830

About Us pageFollow Us:

· Facebook

· Twitter

· Flipboard

· YouTube

· Instagram

· RSS News | RSS SceneArchives

Copyright ©2024 Jansi LLC.

You must be logged in to post a comment.