DC Theater Review: The Oresteia at Shakespeare Theatre

Michael Kahn's curtain call at The Shakespeare Theatre Company is the breathtaking, deeply satisfying "The Oresteia"

In a choice that is as touching as it is powerful, Michael Kahn caps his illustrious tenure as artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company with that most seminal of Greek tragedies, Aeschylus’ The Oresteia (★★★★★). With a beautifully dark, spare, sinewy vision, Kahn gives us one of life’s most enduring struggles: the battle between our volcanic urge for revenge and a quietly abiding, yet momentous, capacity for compassion. This is Kahn in greatest communion with his art, his voice visceral and unwavering, and it is a profound note upon which to take his leave.

The brilliance starts with his commissioning of Ellen McLaughlin to adapt the play with a free hand — and through paring and building, she has hewn the trilogy into a deeply satisfying and most accessible arc. Her inclusion of a vital piece of prequel — the sacrifice of Clytemnestra’s daughter Iphigenia — is pivotal. It’s a choice that sets the emotional stage like no other and Kahn punctuates it with breathtaking stagecraft, as if to ask, how can we not feel that Clytemnestra is righteous in her horror and rage? And yet it begins a deadly chain-reaction that leads to more blood and nightmares.

Even adapted into modern English, the ideas here are writ large and this is less family drama than existential examination. At its heart, The Oresteia is a contemplation of where retribution might end and justice begins. But together with Kahn’s vision, McLaughlin injects a palpable humanity, a sense that the questions raised are never far from our own doorstep, now more than ever.

If this sounds dry, rest assured it is anything but. Set in the shadows of dark, quarry-like cliffs, the House of Atreus is a barren abode that seems to float in space and time. Keeper of this palace of secrets and spirits is the volatile, half-mad Clytemnestra, waiting for her husband, the General Agamemnon, to return from the Trojan War. Watched warily by a Chorus of servants, we soon learn just how indelibly Iphigenia’s death has marked Clytemnestra’s heart and mind. When Agamemnon finally returns victorious, she succumbs to a basic human urge, but in doing so, condemns her family to a legacy of blood. As events unfold, Apollo and the Furies circle unseen like manifestations of unbridled, all-too-human imperatives, until the bloodlust threatens the family’s extinction.

Driving the emotional storm, this Clytemnestra is drawn with great credibility, tacking towards the contemporary, not just in language but manner. Owning this alpha completely, a superb Kelley Curran burns incandescent in all her grief, inconsolable anger, and destructive glory. But if Curran serves it larger than life, she is not without nuance: even when her Clytemnestra is calm, we feel the dark waters beneath her surface running at speed. When they erupt, the display is magnificent.

A convincing match for this powerful woman is Kelcey Watson’s Agamemnon. Quietly exuding this man’s profoundly troubled psyche, Watson offers a subtle mix of warmth, bewilderment, and a leader’s all-embracing commitment. He is so wonderfully-drawn, it’s hard not to seek his side of the story, to ask that age-old question: what, in God’s name, were you thinking?

The Chorus, integral to the Greek tragedy, appear here as watchful house servants, talking to the family as much as to themselves. Like a kind of narrative cocoon, they question and reflect on what they see, rueful, agnostic, until they find by the end that they are no longer bystanders. The verbal choreography is clever and complex, the individual comments rippling through the eight players with perfect timing and potency. Their voices are alternately speculative, critical, and motherly, until they at last transform into McLaughlin’s answer to Aeschylus’ concluding trial. This is a deeply effective ensemble, but standouts are Helen Carey and Franchelle Stewart Dorn for their mother’s stoicism, and Alvin Keith and Corey Allen for convincing intensity.

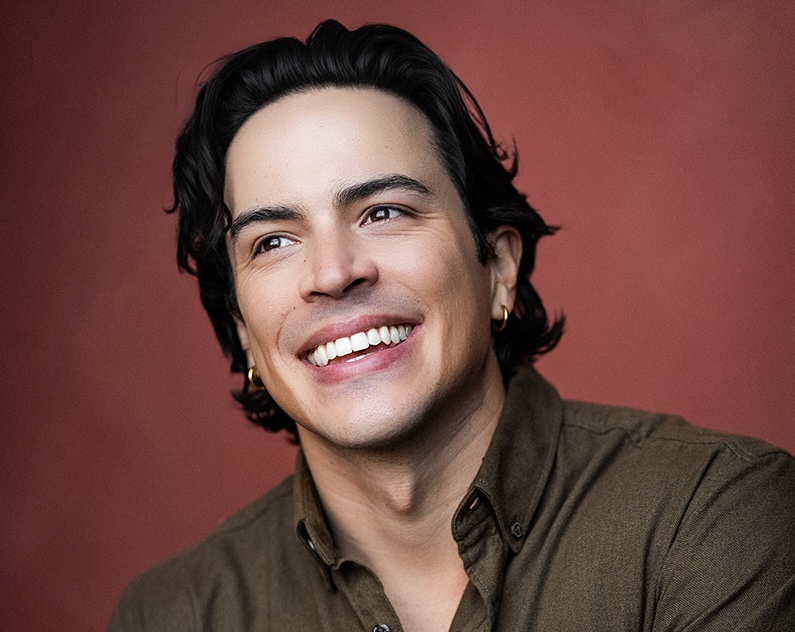

As Clytemnestra and Agamemnon’s adult children, Rad Pereira offers a compelling immersion disturbed young Electra, and Josiah Bania gives his Orestes credible emotional trauma. In the small but meaningful role of Cassandra, Zoe Sophia Garcia is an extraordinary, convincing presence, bringing a phenomenally realized view of the vanquished, a glimpse of all the human promise lost to war and vengeance.

Such are the themes in this extraordinary piece: as long as humans have walked the earth, harm has beget harm in an infinite array, be it vengeful murder or retaliatory war. Can such primal chains be broken and reset into new ways of being? If this Oresteia makes an offer, it is up to us to give an answer. And thus, Michael Kahn leaves us.

The Oresteia runs through June 2 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Sidney Harman Hall, 610 F Street NW. Tickets are $44 to $118. Call 202-547-1122 or visit www.shakespearetheatre.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.