15 Years of a Free Rein

From its first issue in 1994, Metro Weekly has forged a unique path to covering D.C.'s GLBT community

It would be a long life for a dog, long enough for a person to reach adolescence, or less than a blink of cosmic time. Regardless of how you slice it, when it comes to Metro Weekly, 15 is a milestone. Arising from the short-lived Michael’s Entertainment Weekly, Metro Weekly was born in a crisis mode, but that has not handicapped its growth through these 15 years. Rather, so many who have been involved with the magazine revisit the early years of crafting Metro Weekly — with few resources, little time and lots of sweat — with great fondness.

The two central players in Metro Weekly‘s cast are Sean Bugg and Randy Shulman, whose involvements have differed over the years, but who have both left — and continue to leave — their marks on the magazine, today as co-publishers, with Bugg also serving as senior contributing editor and Shulman as editor-in-chief.

“When you start a magazine essentially from scratch, it’s hard to get anything off the ground,” says Bugg. “That Randy was able to do it and very quickly have a magazine that was good, there’s just a lot to respect about that.”

Shulman adds that Bugg has been a good foil for his handling of the magazine over the years, giving them a sort of “odd couple” balance exemplified by so many successful duos of popular culture — Oliver Hardy to Shulman’s Stan Laurel?

“I can sometimes be this little fount of, ‘Let’s do this, let’s do this, let’s do this,’ crazy ideas,” Shulman says. “Sean is far more rational, far more focused than I am. He’s a good balance to my off-the-wall ideas.

“It’s never been easy,” Shulman continues, assessing these 15 years of production. “There’s nothing easy about it. There have been problems along the way, and we’ve tried to solve them. And certainly there are some periods that are smoother than others in a history like ours.”

The birth of Metro Weekly in the spring of 1994 was not one of the smooth periods.

From Michael’s Ashes

RANDY SHULMAN WAS looking for some direction — or maybe just a distraction. The recent end of a five-year relationship didn’t make 1993 a particularly good year. He wouldn’t know that an invitation to a party was about to change his life. That party was in the home of local artist Paul Myatt.

“There were these huge pictures on the wall, drawings, and they were just extraordinary,” he remembers. “[Paul] did the drawings for this little rag called Michael’s. I’d seen Michael’s and I had completely dismissed it. It was beyond horrible. It was edited by illiterates. It was written for illiterates. It was the worst piece of crap you could put onto paper.”

And Shulman wanted to contribute.

Consider it an act of charity, but he insisted to the magazine’s owner, Murray Greenberg — after Myatt had convinced Shulman to offer the arts-criticism talents he had honed in the Hill Rag, The Reston Times and The InTowner to Michael’s — that there was potential. Potential, he explained, that could be realized if he was hired full time.

“It had Myatt’s drawings. It had some talented people working for it. Jeff Code was doing some work for them,” says Shulman, pointing to the photographer who would go on to make “Coverboy Confidential” one of Metro Weekly‘s most popular features. “I thought, ‘He’s got something here, he just doesn’t see it.’

“They just didn’t know what they were doing. I didn’t know what I was doing, but after working with three publications, I certainly had a better idea than they did. I went to Murray and said, ‘You should hire me as editor. I will work toward making this a decent, reputable publication.'”

Sean Bugg, with a casual knowledge of Michael’s, either didn’t notice a change in quality, or was simply not impressed. Myatt, who has since died, arranged a meeting of the two at JR.’s. With his Washington and Lee University journalism degree and a youthful lack of tact, Bugg had no reservations about ripping into Michael’s at that initial meeting, particularly as he had no idea that Shulman had been hired as the new editor in September 1993.

“I was doing my ‘young, idealistic writer’ tirade about how bad the Blade sucked, how bad Michael’s sucked and how the town didn’t have anything worth the fucking paper it was printed on,” remembers Bugg, adding that after a few opinion pieces, he’d already been banned from the Washington Blade for submitting an essay intended solely to criticize that newspaper. He’d also submitted work to Michael’s — a humor column about buying his first dildo — but had gotten no reply. That’s just what Shulman asked him to resubmit.

“It was flat-out one of the most brilliant things I’d ever read,” says Shulman. “It was so funny.” Thus, a collaborative relationship was born, and Bugg became a regular contributor.

With Shulman as editor, Bugg becoming a popular columnist, and Marc Slyman joining as a full-time ad salesperson a few months later, it probably seemed that the magazine was making a turn for the better. Little did they know Michael’s would not see the end of 1994. Without notice, Greenberg pulled the plug in April 1994 after only a year of publishing.

“I basically turned to Marc and said, ‘There’s an ad base here,'” says Shulman. “‘Get them to commit. If we can get this back up and running in three weeks, we can actually have another shot at this.'”

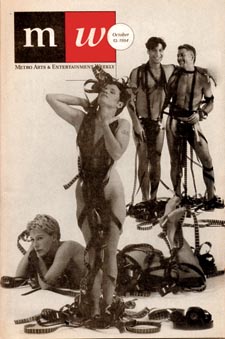

With Slyman handling the business end of things and Shulman editorial — along with some kitchen-table design brainstorming with Bugg — they pulled it off, securing office space, a printer, content, advertising and all the rest it takes to launch a publication. On May 5, 1994, MW — or Metro Arts & Entertainment Weekly — debuted featuring a cover interview with photographer Annie Adjchavanich, who was making a name for herself with her portraiture of female illusionists.

Adjchavanich, e-mailing from Los Angeles, recalls that she may have been willing to serve as Metro Weekly‘s first feature, but she was less enthusiastic about Shulman’s suggestion that she photograph for his new magazine… at first.

“Initially, I was not interested in working for the magazine,” she admits. “It had terrible design: a cover that was crowded with too much type, and lacked real design throughout. No way.

“But many months later, I picked up an issue. Randy and Marc had hired a new graphic designer who had redesigned the logo banner. The design throughout made me take the publication seriously. I decided to meet with Randy and offered to shoot a handful of covers as comps, but then after that they would have to start paying me. I met [art director] Daryl Wakeley and we were off and running. We agreed that less is more: just the logo-banner and my photograph made up the cover.”

With Wakeley’s design and Adjchavanich’s photography, it was a style and design that began to get the magazine noticed. Among those paying attention was Todd Franson, who had recently returned home to the metro area after studying photography and graphic design at Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia.

“In early 1994, I started noticing this little magazine,” says Franson. “It was much more than a ‘bar rag.’ It was more arts, black-and-white covers with no text. I started collecting them.”

By 1995, Franson was able to move from collector to contributor, offering shots he’s taken at a Rehoboth party, “Love ’95,” to Metro Weekly.

“Randy was really impressed,” he says. “I don’t think I got paid, but I was just happy to have something published.”

Franson’s contributions wouldn’t stop there. While Adjchavanich was doing much or her work in the studio, Shulman needed a photographer in the field. From day-long documentation of the workings of Food & Friends, to shooting Sir Ian McKellen at the Four Seasons Hotel, Franson was up for nearly anything Shulman could throw at him, which didn’t stop with photography. Reviewing music and shows, shooting covers, assisting Slyman with pasting up the magazine — in those days layout happened in the real world, not the virtual — Franson became the assistant editor, putting in about 60 hours a week. The cycle would end around 11 p.m. on Tuesdays, with Franson, Shulman and Wakeley heading to the since-closed Circle Bar to plan the next week’s issue.

Those early years also included Nancy Saiz, who came on to replace Wakeley as art director. (Wakeley, though still in the area and credited with some brilliant design work for Metro Weekly, declined to be interviewed for this story.) Saiz, the second woman to join the operation, and a longtime friend of Slyman’s, who died in 2007, says she was not very familiar with Metro Weekly when Slyman and Shulman approached her about doing a redesign.

“I’d seen it, but I hadn’t read it,” she says. “I think at the time it was more geared to men.”

Involving herself in the intimate work of redesigning the magazine, as well as working regularly on Metro Weekly‘s production, Saiz says she came to view it differently.

“I was really impressed with the content, the interviews, the level of expectation the editors had of their writers,” she says. “For being such a small publication, it was very ambitious. It wasn’t a rag. I think they pushed the envelope with what was possible with newsprint.” ·

Mike Heffner, a partner in 202design, followed Saiz. With a redesign just completed, he spent his three years with Metro Weekly focused on the production components — even if that meant becoming more familiar with sunrises.

“The first issue for me, Randy and I completed it at 6 a.m.,” Heffner says, a hint of that exhaustion creeping into his voice. “Once any publication is printed, it looks polished and refined. Nothing is like that on the inside. It was fun and fantastic — and it was exhausting. I was able to refine how it was being produced. It was always a little crazy, but it worked.”

What also helped Metro Weekly to work was finding talented writers. Craig Seymour was one such freelance writer, who started contributing as a music critic at the same time Heffner joined the magazine. Seymour, who left D.C. to write for Entertainment Weekly, has since published a memoir of his time as a stripper in Washington, All I Could Bare, and serves today as a journalism professor at Northern Illinois University. He credits his time at Metro Weekly for launching his career.

“Randy pretty much gave me free rein to do whatever I wanted to do, and I was able to develop my voice as a critic,” he says. “The conversations I had with him about style were really invaluable. I had someone very supportive of my writing in Randy. And Sean’s sex columns were always fun!”

With the contributions of so many, Metro Weekly made it through its formative years. And with the turn of the century looming, the magazine continued to grow, and to change. Adjchavanich, Wakeley, Saiz and others had come and gone. Slyman and Franson left the magazine in 1998, though Franson still did freelance work. Heffner held on until 2000, when his own business was taking off. But Shulman wasn’t going anywhere, Bugg continued to contribute, and other new faces were just around the corner.

The Middle Kingdom

KENDRA KULIGA STARTED working for Metro Weekly in the late 1990s. She’d become acquainted with Shulman by working in the photo lab near his home, where he’d drop his copious rolls of Metro Weekly film for processing. A photographer herself, she eventually asked if she could shoot for the magazine. She’d be doing more than that, coming on not only as a photographer, but as an archivist to bring order to Metro Weekly‘s boxes and folders and piles of photographic chaos.

One of the memories that Kuliga offers, however, has less to do with her and more to do with yet another art director. Heffner’s departure could only be followed by another’s arrival.

“I remember getting Tony Frye’s résumé through the fax and saying, ‘You have to hire this boy.’ It was so beautifully laid out,” says Kuliga. “He ended up being a rock star.”

During this second stage of Metro Weekly, Frye wouldn’t be the only rock star. It was really more of a band.

“Everyone who’s worked for us, I see enormous potential in,” says Shulman. “Jonathan Padget was tremendous. Will Doig was capable of extraordinary things.”

Along with writers Padget and Doig, and the aforementioned Kuliga, there was also photographer Michael Wichita.

“The late ’90s, early 2000s, it was a very fertile time, creatively,” says Wichita, who credits Adjchavanich’s Metro Weekly photography for playing a part in changing the course of his career.

“I was at College Park, an architecture student, when Metro Weekly had just started,” Wichita says of his advanced studies at the University of Maryland. “Annie was the photographer, and it just kind of spurred me on: ‘Maybe that’s what I should be doing.'”

He answered his own question by transferring to the Rhode Island School of Design to study photography. Afterward, back in D.C., he approached Shulman about shooting for Metro Weekly, landing the 1998 Atlantic Stampede as his first assignment, then coming on full time.

“Once I was on the inside, it was great. It was Shangri-La. It was a place you could pitch your craziest ideas, and most of them would happen.”

It’s a simpatico point for Doig.

”We were basically allowed to do whatever we wanted to do with it every week,” says Doig, characterizing the period during which he worked full time at the magazine, roughly the end of 2002 to middle 2004, as Metro Weekly‘s “golden era,” with Bugg becoming editor-in-chief. “We did all these stories that were completely different. It was exciting to be given free rein. They sent Michael and me to [Walt Disney World’s] ‘Gay Days.’ We just wandered around and wrote about it. I’m sure I thought it was this David Foster Wallace piece. I wrote a history of the Cairo building. They just let us do these long, in-depth stories. There was a crackdown at big clubs, and they let us do this three-part story. It just seemed like this big, fun adventure. I’ve never had a freer job.”

Doig says that while he misses the freedom, having moved on to New York Magazine, Nerve.com, and now features editor at Tina Brown’s The Daily Beast, he doesn’t miss the restraints of the era, such as the office sharing a single AOL e-mail address that would go offline whenever the fax was in use.

Padget, now a Washington Post copy editor, also has fond memories of the magazine, though he jokes about the headaches, too, in retrospect.

“I don’t miss the early 7 a.m. proofing at Tony Frye’s,” he says. “Sean would pick me up to do proofreading. We’d go to Tony’s and sit there. I would try to stay awake. Just because of the size of the staff, things were coming together so at the last minute. I never wanted to see errors in the magazine, so I was happy to do it — but I don’t miss it.”

He does miss other things.

“I miss the camaraderie of a smaller staff. I miss the sort of intimacy of it. Seeing the passion from Randy, Sean and my colleagues at the time, these weren’t people just doing it to make a buck. There was a real sense of community, a sense of purpose.

“And I was very proud of my body of theater criticism. That was a great sort of cultural training for me. I loved just meeting some of the people, iconic people — Jerry Herman, Boy George — ‘I’m on the phone with Boy George! He’s not very interesting. But I’m on the phone with Boy George!'”

During this “golden era,” Metro Weekly also managed to secure Kristina Campbell, editor of the Washington Blade when she resigned in 2002, as a contributing columnist.

“I always thought of it as a really nice publication,” she says of Metro Weekly. “Sean called me and courted me and said he wanted me to write a column. I knew him from when he was an [ACT-UP] activist. I interviewed him back in those days. I remember him being really nice. He was friendly and chatty.

“I thought about it for a couple of months. Then Paul McCartney said he was getting married to a chick about my age. I wrote about that.” And Campbell’s “Alphabet Soup,” which ran for about three years, entered the Metro Weekly fold.

To better showcase all this talent, Frye spent most of 2002 working on a redesign for the magazine. He says that he advocated for a style he calls “bar rag with a brain,” generally out of frustration that the growing magazine was having trouble shaking its Michael’s roots. But Bugg was not buying it.

“The term ‘bar rag’ would almost make Sean vomit,” Frye says with a laugh. “Looking back, it was a very smart thing. I’m glad he held his ground.”

But nobody had a problem with adding “Coverboy Confidential,” which Frye also proposed, even if he himself found the idea a little daunting: “I didn’t think we’d be able to do a year. I was thinking, ‘How am I going to find 52 dudes to do this?'”

Thankfully, Jeff Code was able to find a project that fit him like a glove, managing to not only do the shoots, but recruit many of the models himself. While he otherwise loves the shoots, Code says his only frustration is that his coverboy recruiting is often met with guys telling him they’d long wanted to do it, but didn’t have the nerve to apply directly.

Adds Shulman, “I’m probably the only person alive who thinks ‘Coverboy Confidential’ is a great sociological experiment.”

The idea behind adding the “Coverboy” feature, says Bugg, was to create a grassroots alternative to conventional beefcake. “The whole point of that section was to get away from what other gay publications have done traditionally, which is you put together a nightlife section and then you go to the Falcon Web site, pull off a bunch of pictures of porn stars, and plaster them all over the place,” says Bugg. “Not that I’ve got anything against porn stars — love ’em — but we wanted to do something different. We wanted to get the people you see in the bars around here, who are local, and shoot them ourselves. And not make it quite as tawdry.”

Padget, who can take credit for about half the “Coverboy” questions readers see today, says he still can’t pass his own nightstand without making a quick inventory of what sits on its surface.

By design, “Coverboy Confidential” may be the only piece of content that does not run on the Metro Weekly Web site, mastered by David Uy. There’s always an argument to be made for keeping some things in print only. Or course, for the “Coverboy of the Year” contest, Uy annually retools the Web site to feature those handsome mugs and allow for online voting.

“We had a ‘dot-net’ site back in the ’90s,” Bugg grimaces. “It wasn’t really functional. It kind of just died. When David Uy came over, that’s when the Web page took off. Almost total credit goes to David.”

Glossy and Newsy

WITH THE ADDITION of coverboys and a worthwhile Web site, and the loss of staff and contributors such as Kuliga, Campbell, Doig, Padget and Wichita, Metro Weekly continued to find its footing, taking ever larger steps. And new faces always appeared to replace those who left. Or, in the case of Todd Franson, a face from the beginning came back full time, serving today as art director.

What might be dubbed the “current period” has also seen changes in style and content. The front of the magazine is dedicated to news. A consumer section, “Domestic Partner,” has been added. And, perhaps most notably, there is that lovely glossy cover, which has been a long time coming — in the works for 10 years, by Wichita’s count.

Franson, always a fan of some of the sillier content of Metro Weeklies past, seems more than pleased by where the somewhat more mature magazine finds itself today.

“It was fun being goofy back then. It was really fun,” says Franson, with a particular fondness for a Halloween issue that featured Jim Graham, then Whitman-Walker’s executive director, in drag. “That was part of our adolescence. There’s a different responsibility now. I would still like to do another April Fools’ issue, but I don’t know how we’d handle it. There was a naiveté we had back then. We don’t have that anymore, and that’s a good thing.

“It’s a stage that’s appropriate for 15. We had to go through all those stages to get to where we are right now.”

As things change, however, conventional wisdom demands some continuity. Where Shulman, Kuliga and Wichita were once the faces that greeted bargoers with requests to photograph them for Metro Weekly‘s pages, that now largely falls to Ward Morrison, himself coming to the magazine as the subject of one such shoot. In the Metro Weekly office to purchase a photo of himself at the 2003 High Heel Races — where he came in third — he asked about photographing for the magazine. Today, so many recognize him as the magazine’s nightlife ambassador.

“I love it,” Morrison says with signature glee. “I’m an emissary. I am genuinely greeting the community as a representative of Metro Weekly, but they’re genuinely friends. I hug and kiss the majority of everyone I see. The most beautiful part is the depth and breadth of what the community has offered me to photograph. Now it’s hard to walk down the street and not know anybody. But Metro Weekly is about community. It’s almost like Metro Weekly is a friend. It’s been about and for the community for so long.”

It’s also been about the arts, whatever resources now go to news. And Shulman could not be happier with the current arts writers: Tom Avila, Tim Plant, Doug Rule and Kate Wingfield.

“Art criticism has always been an important component of this magazine,” says Shulman. “Right now we have some of the most exceptional critics we’ve ever had.”

Rule notes that it’s such criticism that’s allowed him to contribute to a trend in dance music, giving greater recognition to the vocalists on celebrity DJs’ offerings.

“When Deep Dish didn’t credit a local singer,” he offers as an example, he wrote about it. That singer, Anousheh Khalili, wrote Rule to thank him for his efforts. “I sometimes think only my friends read it, but the little instances like that make it worthwhile.”

While Shulman continues to nurture the arts coverage as editor-in-chief, Bugg’s news-junkie jones plays out as senior contributing editor, most recently by writing an in-depth cover story on the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for the March 5 issue. Those efforts are buttressed by managing editor Will O’Bryan and staff writer Yusef Najafi, both of whom bring their prior experience writing in the GLBT press to Metro Weekly‘s pages.

“While nobody is perfect and there will be people who will have bones to pick with our coverage of some communities or topics, since we’ve come on the scene I think we’ve gone out of our way to really embrace the black GLBT community, the transgender and drag communities, the leather communities — all the separate parts of the community that I think used to feel they were being left out in coverage, particularly because so much hard-news coverage is about Congress and this and that,” Bugg says of Metro Weekly‘s approach to news. “The best thing we probably brought to the table was treating all of those groups as equal parts of the community and valuing them for who they are.”

Finding the Future

WHETHER NEW MEDIA or traditional media, print or broadcast, there is no doubt that news outlets are in for the biggest shakeup of their existence since the days of Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. What media will look like 15 years from now is still anybody’s guess.

“We’re going to become more of a multimedia content provider,” Bugg says, granting that a mountain of variables remain. “In the future, everyone’s a broadcast journalist. That writing is on the wall. What role print plays in that, and for how long, that’s the question everyone’s asking: How long is this print product that essentially monetizes everything else we do, how long is that going to last?”

As art director, Franson is perhaps the most married to the tangible product. He can point to changes he’d like to see — becoming fully glossy, adding more sections — but he’s not ready to give up paper.

“I’m definitely a print guy,” he insists. “I’d much rather read a magazine than something on a computer. Maybe I’m a dinosaur. I still look at the magazine as a kind of precious object we create every week.”

Though Bugg’s home-décor mantra could be boiled down to a simple phrase — “more books” — he’s already reading on a Kindle. Shulman’s perspective may fall somewhere between Bugg’s and Franson’s, with all sharing a paper-bound sentiment.

“I’m going to be an optimist and hope that there’s always a print component to Metro Weekly, even if online becomes the dominant form in the next 10 to 15 years,” he says. “The magazine will have to find ways to broaden itself, broaden its coverage online. But the simple answer is I don’t know. I don’t know what the future holds. I only know that we’ll be there to figure out how to make it work for us, and how to make it work for our readers.”

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!