Family Care

The people of the Carl Vogel Center turn health care into community

It’s unlikely you ever met the late Carl Vogel. If you’ve seen his playwright sister Paula Vogel’s Obie-winning Baltimore Waltz, you may have at least some familiarity with a vision of Carl through his sister’s eyes. Obviously, the Vogel family has strong family bonds. So much so that while Paula Vogel wrote a play remembering her brother, their father, Don, launched the Carl Vogel Center in their D.C. hometown.

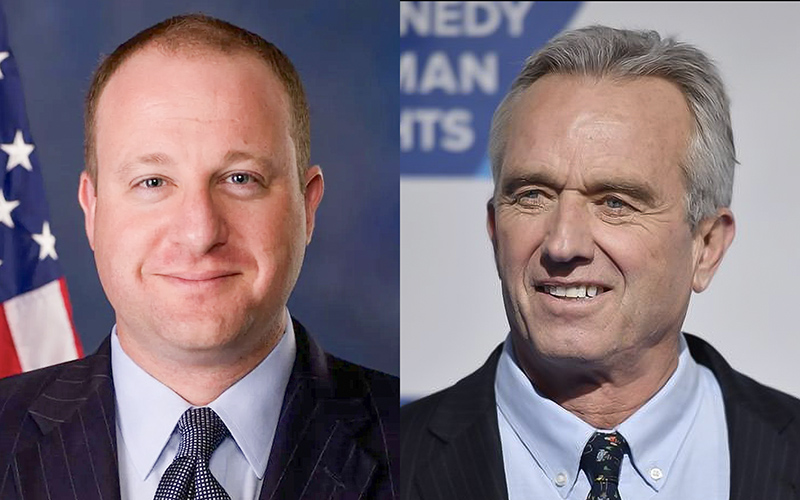

William Campbell (left) and Lloyd Buckner

(Photo by Todd Franson)

With Carl Vogel dying of AIDS-related illness in 1989, the 1990 launch of his namesake center sought to counter some of the suffering of the time with HIV/AIDS health services. Today, operating out of an office building at 1012 14th St. NW, the Carl Vogel Center has expanded its services to become a ”multidisciplinary and integrated” primary medical health care center.

The growth, however, has come with challenges. Funding restrictions, complaints about the center’s food bank – a victim of its own success — and D.C.’s ongoing infamous distinction as the U.S. city with the highest HIV-infection rate, are a few of the considerations the center tackles.

The pillars supporting the center seem solid nonetheless. Ahead of World AIDS Day, Dec. 1, Metro Weekly introduces you to four of those pillars, who keep the center evolving and the ”family bonds” as strong as those inspired by the Vogels themselves.

CARE WITH HEART

SOME DAYS ARE harder than others.

For Angela Brown, community outreach coordinator at the Carl Vogel Center, this past week got particularly difficult when she came upon a new client from Maryland who had been suffering from illness and weight loss.

”She was going to see all these different doctors who were telling her it was all in her head and they had her on depression medication until she got referred to an oncologist who told her she had been misdiagnosed —

she had HIV,” says Brown. ”For them to tell her it’s in her head and not do a simple HIV test, it just breaks my heart. I was happy that we could help her. That reassured me that what I’m doing is important.”

Brown has been at the center since 2004, managing counseling, testing, referral and outreach services. She’s also the clinic’s ”Red Carpet Ambassador.”

”That’s a program for those who are newly diagnosed,” she says. “They can come in and receive services, and I try to remove as many barriers and red tape as possible.” She adds that there’s no waiting list to access services and that new clients are often given care within 24 hours.

Among the staff at the center, Brown, who is a medical assistant as well, has been there the longest. Her first role with the center was as an outreach worker. ”I have some kind of sickness where I just like to help people,” she says with a smile.

”What drove me to the Carl Vogel Center was HIV more than anything else,” she continues. ”My whole life, I’ve worked in some capacity of helping people, and HIV in D.C. was getting to be so outrageous I couldn’t ignore it. I had friends who passed away, friends of friends, family of family – it was just exponential and there’s just really no need when it’s as simple as using a condom.”

During her six years at Carl Vogel, Brown has watched the organization change in terms of the care that’s provided.

”It’s become a little warmer than it used to be,” she says. ”Instead of you coming in and your case manager knowing your name as soon as you walk in the door, everybody knows your name.”

Brown’s own path to the center wasn’t a direct line. Growing up in the D.C. area, she had hoped to become a lawyer.

”As I got a little older I thought I would go into nursing, or work with computers, or become a masseuse,” she says. ”I figured with the masseuse, too many occupational hazards. With computers, I’d probably go crazy sitting in front of one all day long. I like interacting with people. So I became a medical assistant and ended up drifting into this field. Luckily, a lot of the skills were transferable.”

Before working for the Carl Vogel Center, Brown spent time with the Women’s Collective, as well as another organization called Our Children, where she did outreach work among youth talking about HIV, safer sex and the dangers of substance abuse.

(Photo by Todd Franson)

”These topics were always around. Personally, I didn’t go through a lot of them, but a lot of my friends always relied on me as someone to talk to, or for information and education.”

Now at the center, Brown finds she’s needed most for support. ”I reassure clients with HIV that it’s not over. I reassure them that this is manageable – you just have to do your part. I reassure them that we’re here on your side ready to help you.

”There’s a certain line you should never cross as a professional,” she concludes. “You want to leave it all at the office. But sometimes it’s hard. Because I come at it from a different approach – I genuinely care – so I’m listening to you. It’s not just [checking off a form]. I guess it affects me more than it should. But if I don’t hope, who can?”

TIRELESS AT THE TOP

AT A STAGE when people are thinking of winding down their careers, Lloyd Buckner was no different. For more than 20 years, he had worked for the District of Columbia, most recently as a senior manager with the Rehabilitation Services Administration, helping disabled residents find employment or otherwise become more self-sufficient.

But blocking Buckner’s intended retirement of fly-fishing and golf was a tiny hitch: a member of the Carl Vogel Center’s board.

”She knew of my capacity to raise money,” Buckner says matter-of-factly, pointing to his volunteer history with various community-based organizations in the area. In a sense, Buckner was drafted to the cause. He’s not complaining, though — serving as executive director of the center is one of the most fulfilling positions he’s ever held. That satisfaction has translated into growth for the center.

Under Buckner, Carl Vogel has hired a full-time physician, expanded its food bank and broadened its mission.

”After coming onboard and realizing the breadth and scope of what confronts people in the city, we decided to change the direction of Carl Vogel from being solely an HIV/AIDS facility to a primary health care organization,” he says. ”As recently as last week, we had 27 new patients…. I’ve experienced in my two-and-a-half years here very little negative feedback about where we are today. I think we’ve kept our eye on where we’ve come from.”

With that growth, however, has come more than just a few growing pains. The food bank, for example, hit a painful deadline earlier this month on Nov. 19 as the center dispensed groceries for HIV-positive clients’ Thanksgiving dinners along with regular foodstuffs to last a week.

”Last year, we gave out about 175 turkeys,” Buckner recalls. ”In 2008, we doled out 10 tons of food from a conference room only 24-by-18 feet. We received a grant from the city in 2009 to expand our food bank and went from every other Wednesday to every Friday. We hit the 2008 threshold in the first three months of the year. We quadrupled the quantity of food that we disperse. However, the landlord has asked us to discontinue our food bank. Seemingly, there was a complaint with there only being two elevators. It serves approximately 200 to 225 people weekly. It was asserted that the patronage clogged the elevators on Fridays. To mitigate that, we partner with a church in far Southeast, where 40 percent of our patients pick up their food.”

(Jansi LLC, which publishes Metro Weekly, is also located at 1012 14th St. NW and shares the same landlord as the Carl Vogel Center.)

Still, mitigation is not a solution. That’s why Buckner juggles — and it’s the juggling that gives one the sense that Buckner will find a way to both satisfy his landlord and keep his food bank going. He’s also juggling changes to Ryan White funding that have dramatically reduced the portion of grants that can go toward mainstays such as rent and salaries.

Rather than complaining, however, Buckner seems eager to navigate the future of the Carl Vogel Center with gusto. On that map, he sees electronic medical records, a standalone facility, establishing annual fundraising events and raising the center’s profile overall.

”It didn’t take me long after being on the board and getting in-house to see that we could not be in a single-niche market. It just would not be smart,” he says. ”We need to be a multidisciplinary, integrated health care facility that serves the residents of metropolitan Washington. All Americans need good, solid health care. If in any way I can facilitate, I have and will.

”I’d like people to know that we’re here, that we have an interdisciplinary approach to medicine, a holistic approach to serving an array of issues that confront people. It’s more about just letting people know that we exist. We have been very quiet. We’re not quite as quiet anymore. Let’s say a new broom doesn’t always sweep better, but it does sweep different. And I’m a new broom.”

SMALL CLINIC, BIG SERVICE

WILLIAM CAMPBELL WAS in his early 20s, working on an agricultural Peace Corps mission in Paraguay in the 1990s, when he had an epiphany.

”I was just struck by the poverty and preventable illnesses that I saw down there,” he says. ”I would see little kids with ‘wet malnutrition,’ a protein deficiency. And you would see these kids with distended bellies. You just wanted to help them. It got me interested me in health.”

Once back home, Campbell got involved in health education in Denver, his hometown. That work led to a master’s degree in nursing from Johns Hopkins University in 2003, and then working at the Carl Vogel Center as Director of Clinical Programs

”When I started here [in 2006] there were about 30 medical patients,” he says. ”In that time they were all HIV-positive, over 90 percent of them were African-American males. Of those, I’m not sure how many identified as gay.

”The clinic has doubled its size every year that I’ve been here. [And] the board made the ultimate decision to expand our services to the greater community so we don’t strictly see HIV patients per se anymore. Although we definitely have that as a core focus, we now see the surrounding communities, so our clientele has gotten extremely diverse.”

Campbell, who is gay and lives on Capitol Hill with his partner of the past 11 years and their three cats, says the center provides services to more than 200 HIV-positive patients and close to 600 others. There is also the food bank, mental health services and case management.

”I think one of our core strengths is that we have a lot of services under one roof,” he says.

Lloyd Buckner

(Photo by Todd Franson)

While Washington is the home of several health organizations, Campbell believes the Carl Vogel Center offers something different.

”Although we are growing, we are still a small clinic with a friendly atmosphere,” he says. “That is what sets us apart from some of our larger competitors. Patients are more than just a number here and we truly focus on the whole patient, not just lab values.”

As far as services go, Campbell says the Carl Vogel Center is moving toward following a ”medical home type model” where most of a patient’s care is provided.

”We are an internal medicine clinic … and my background is in family medicine, so we can tackle a lot of different problems. We want people to look at us as if we are their medical home. The East Coast is kind of the home of fragmented care, where everybody sees all these sub-specialized providers, and there’s not really good evidence that that provides better care.

”A lot of trends in health care are going toward this medical home model when you really have a primary-care home where your basic needs are taken care of,” he continues. “Then, if you need specialty care you’re referred out. But your primary care should be able to take care of most of the needs that you have. From basic GYN care to preventive services.”

And this is a good time to seek services at the center, Campbell says, because the organization has the capacity to take on new patients.

”We also have convenient hours,” he says, adding that on Mondays and Wednesdays the clinic offers evening hours, sometimes as late as 8 or 9 p.m. On Mondays and Tuesday, the clinic opens at 8 a.m. ”So we’re set up for the working adult.”

The Carl Vogel Center is also set up to see patients without much notice, as it operates with about two ”access spots” set up in the daily schedule for each provider per day. That means that when patients need immediate care, the center should be able to accommodate them.

”We’ve built in these special spots that are not supposed to be pre-booked. They’re held for about 72 hours before so that we can accommodate those kind of urgent visits and keep people out of the [emergency room],” he says. ”We also want those patients to have access to their medical home.”

EASY BEING SEEN

WHEN KERMIT TURNER learned he was HIV-positive, the world was a much different place, particularly with regard to the epidemic. Circa 1990, AIDS was burying the gay community. Amid that devastation, the Carl Vogel Center appeared as a bright spot.

Kermit Turner

(Photo by Todd Franson)

”The infrastructure currently in place did not exist,” the 56-year-old Turner says of HIV/AIDS services found in the city today. ”Everybody was scrambling to position themselves to protect their lives. There were all kinds of theories going around, different ways to help yourself. One of the ways was this herbal type thing, … and [the Carl Vogel Center] had a kind of ‘herbal corner.’ There were magazine articles making suggestions on how one could keep one’s blood clean, how one could enhance one’s health. I’ve always been into that kind of thing anyway, and they had that there. I purchased a bunch of herbs and vitamins and things, and it seemed to help tremendously. But then I lost track of them.”

While the tumult of the era separated Turner from the center, the split wasn’t permanent.

In 2007, Turner received care at D.C.’s Sibley Hospital. Upon being released, a social worker wanted to ensure Turner’s continuation of care, and suggested he begin a relationship with a new health-services provider – steering him toward Carl Vogel.

”I wasn’t really sure what she was talking about. ‘Carl Vogel Center? I thought they were gone.’ She said, ‘No. In fact, I prefer that you go there, because I know the people there. I think you’d be a good fit. They’re very warm, family-oriented people. Just perfect for you.'”

And now that Turner is back in the fold, he is thriving – even going so far as to join the board. As promised, a perfect fit.

When it comes to accessing health care services, Turner prefers the center to other providers, such as Whitman-Walker Clinic, because it’s smaller. The clinic may offer dental care, a pharmacy and other services beyond the Carl Vogel Center’s current scope, but the trade-off works for Turner.

”Whitman-Walker is okay, so are other places,” he says. “In fact, I deal with them on support-group levels. But I find that this facility here is the right size for me. I don’t get lost in the mix, if you will. They’re smaller, but that’s what I need for me. I have a one-on-one with them, with everybody on the staff. I really enjoy coming here. I’ll stop by because I happen to be down here, just drop by and say hello.”

Another consideration for Turner is that he’s gay. While the center’s namesake was a gay man, and center staff do outreach to gay bars, sexual orientation is not an overt component of the center’s work. Turner prefers it that way.

”They seem to approach people from the philosophy that I approach people from,” he says. ”They never got into labels. They just deal with the human being, and that’s what I love about this place. There’s none of this, ‘He’s gay, he’s straight, he’s bisexual, she’s bisexual, she’s a lesbian.’ There’s none of that categorization. We don’t need that. We’re all trying to solve the same problems: We’re trying to get medical care and we’re trying to get from one day to the next. Labels get in the way of all that.”

(Photo by Todd Franson)

Certainly nothing has gotten in the way of Turner accessing center services. When asked which services his uses, his answer comes quickly and with a laugh: ”As many as I can.” Beyond his routine blood work, Turner has attended various support groups at the center, used their acupuncture and massage services – till the grants for those expired – and picked up groceries from the food bank.

As a volunteer member of board, however, it’s not as though Turner’s relationship with the center is purely a one-way street.

”I feel that I have something to add,” Turner says of his contribution to the board. ”I know a lot of the clientele/patients. I know a lot of the staff. I understand what the center’s goals are. Contribute your time, your money or your talent. And I don’t have any money, but I do have some talent and I do have some time, so I can at least do that. I’m trying to give back to my community as they have given to me.”

For more information about the Carl Vogel Center, located at 1012 14th St. NW, Suite 700, call 202-638-0750 or visit carlvogelcenter.com.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!