Gavin’s Story: Gavin Grimm is the new face of the transgender movement

When his high school offered Gavin Grimm a modified broom closet as a restroom, he not only refused to use it, he sued the school board. Meet the new face of the transgender movement.

For Gavin Grimm to come out as transgender, the Internet was key.

“I don’t know where I’d be without it,” he says. “People love to demonize it, but it’s got innumerable positives.”

The Internet provided a portal to possibility, helping Grimm realize that the female body he was assigned at birth was conflicting with his true identity. It was a feeling that had existed since he was young, but Grimm had never had the language to express it — until he saw anime cosplayer “twinfools” transition from female to male.

“It was so magical to me,” Grimm says. “It was the first time I’d seen anything represented in media, or in my life whatsoever, that suggested that people could change gender. And I saw the video and thought, ‘This is an option.'”

The experience was liberating. As a child growing up in rural Gloucester County, Va., Grimm struggled to fit in, never quite adhering to people’s expectations of how he should behave. He mostly hung out with boys and preferred masculine activities, but had a hard time making friends, and there were periods where he was very isolated. During those lonely times, he found an outlet in the game Pokémon, which he also credits with helping find his identity.

“It’s a role-playing game, so I could play as one of two players, male or female. From the start, I don’t think I’ve had a copy of the game where I wasn’t playing as the boy character,” Grimm says. “Early on, I rationalized it: ‘Oh, it looks cooler.’

“That was a bridge to self-expression, because when we’d go to the store, there weren’t any Pokémon shirts in the girls’ section,” he continues. “So I’d be like, ‘I want to go over here. They have Pokémon shirts. I’ll just get one or two.’ And then, very gradually, that evolved to me just going straight to the boys’ section. I wouldn’t even entertain the thought of going to the girls’ section.”

Initially raised Southern Baptist, the now-atheist Grimm struggled with a long, arduous coming out process, both to himself and, later, to his family. He first told a trusted aunt, and then his mother, who told him she loved him, but also wanted him to keep it a secret from the rest of the family. Things eventually came to a head on Grimm’s 15th birthday.

“I had been, the night before, absolutely catatonic with grief, because I knew that I was going to wake up the next day and I was going to be the birthday girl,” Grimm says. “And I thought I just wanted that part of my life to be over. I didn’t think I would be able to make it through another one of those birthdays, and actually, I don’t think I would have.

“So the next morning, I woke up crying, and just feeling dead. I stumble down the stairs, and I look at the birthday cake, and it’s addressed to me and my [twin] brother. And the cake says the wrong name. And I was like, ‘You couldn’t even have left the names off? You couldn’t even have done that for me?’ I got upset and we fought.”

Grimm returned to his room, sobbing, when his mother called him downstairs an hour later.

“I hobbled downstairs, after quite a bit of prompting, because I just didn’t have it in my bones to move, and she had wiped off the wrong name on the cake, and written ‘Gavin’ with expired green gel icing from the deepest recesses of our cabinets,” he says. “But it was the best thing I’d ever seen in my life.”

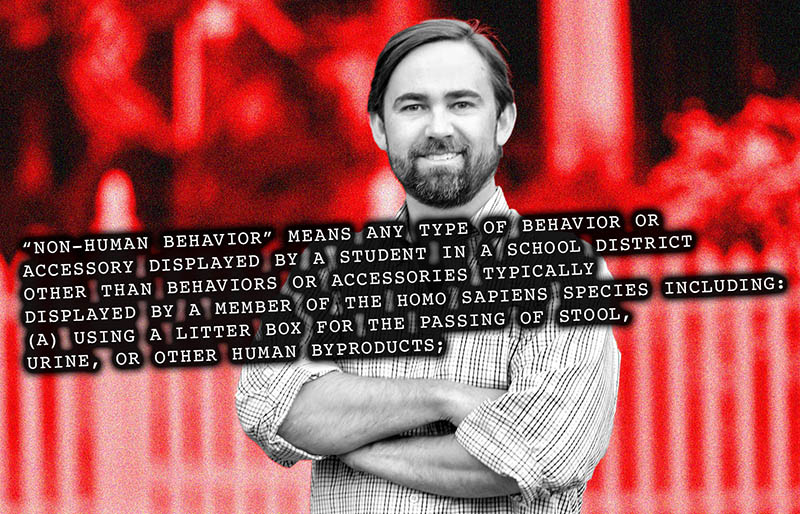

At the beginning of his sophomore year, Grimm informed administrators at Gloucester High School of his transition, armed with a note from a licensed doctor diagnosing him with gender dysphoria. After a couple of weeks and very little negative reaction, Grimm asked to use the boys’ restroom. The school approved his request, and he used it without incident until an anonymous complaint from a member of the community. It brought the issue to the attention of the Gloucester County School Board, which placed Grimm at the top of its meeting agenda. At the meeting, community members railed against Grimm using the boys’ restroom. One speaker even compared him to a dog that urinates on a fire hydrant. “It was kind of strange, because I’d had no funny looks,” says Grimm. “Nobody had spoken to me in the restroom. I had no altercation of any kind whatsoever in those restrooms. I had just used the bathroom like any other person. I used it, and I left.”

The board later voted 6-1 to institute a policy in which Grimm was barred from the boys’ restroom. In addition, he and any other transgender student would be afforded the chance to use an “alternate, private facility,” which turned out to be three or four old broom closets that had been hastily configured into unisex bathrooms. And unlike what school board members claimed, all of the bathrooms were unusable for four or five school days after the vote. Grimm refused to use them, instead opting for the bathroom in the nurse’s office.

With the help of lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Grimm sued the Gloucester County School Board. His lawsuit claimed the school had violated Title IX and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Although a federal judge threw out part of his lawsuit and refused to grant Grimm an injunction to use the boys’ restroom, it was eventually fully restored by the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that lower courts should consider Title IX’s protections against sex discrimination to apply to transgender students.

“Part of me was relieved, because it felt like things were finally coming to a close, that these two years of my life were finally coming to the head that I’d been waiting for from the very start of it,” Grimm says of the 4th Circuit’s decision. “My life has essentially stopped because of this. Everything I do now is with regards to what’s going on now. When I make doctor’s appointments, I have to make sure I don’t have any legal anything I’ve got to do, or any interviews, or whatever. It consumed my life, and still is consuming my life.”

While Grimm’s lawsuit must still be decided on its merits, the 4th Circuit’s decision represented a major victory for both Grimm and the larger transgender community. And, if the courts decide that Gloucester County’s restroom policy is unconstitutional, it could have far-reaching ramifications, including affecting anti-trans laws in other states. The possibility of having a positive impact or a chance to make others’ lives easier means a great deal to Grimm.

“I know what I’ve been through, and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy,” says Grimm, who, on the advice of his laywers, was not permitted to discuss the lawsuit in detail. “I genuinely can’t think of a single person I would want to go through this. That I have the opportunity to ensure that, hopefully, fewer kids — or anybody — will have to go through this in the future, makes me feel good about what I’ve done. Because this isn’t something anyone deserves to face.”

METRO WEEKLY: Tell me about your family.

GAVIN GRIMM: I live with my twin brother, and my mom and dad. I have an older sister by my mom, and two older half-sisters by my dad.

MW: What do you like to do for fun?

GRIMM: I like to go places — anywhere — I just like to be out and about. I just got back at two in the morning from Lunatic Luau, which was a blast. It was a concert, with bands like Ghost and Shinedown and Five Finger Death Punch, and other bands like that.

MW: Were you interested in sports as a child?

GRIMM: Yeah, as a kid, my brother and I both did T-ball with Parks and Rec. But then we got older, he went on to baseball, and my only option was softball. I absolutely refused to be on a female team. I was not at all comfortable with that. And the other thing, I didn’t want to play softball, I wanted to play baseball. I saw softball as discount-store baseball, and I didn’t want anything to do with it.

MW: When did you first realize that you identified as a boy?

GRIMM: It wasn’t in my vocabulary for a very long time. I recognized the feeling, and had I had the words to express it, I probably would have been expressing it as early as age five. Or perhaps even earlier. The closest thing I got to articulating it as a kid was that I would frequently insist that I was the same as my twin brother. That was my wording: “I’m the same as him, I’m the same as him!” And there was a very long period of time where I wasn’t cognizant of the differences in our sexes. I just thought we were the same. I knew people treated us differently, but I knew that I was “like him.” And people just took it to mean, “You’re a tomboy,” or whatever. I knew that it wasn’t what I was getting at, but I didn’t know how to more correctly articulate what I was feeling.

MW: When you were younger, did you generally gravitate towards boy things or traditionally “masculine” activities?

GRIMM: By and large, the activities I chose involved me spending my time out in the woods. I was climbing trees, or messing with bugs or snakes that probably should have been left alone. Or I would play Army. I can remember many fights I had with my brother, because he wanted to make me the medic, because I was “the only girl” there. And I was like, “Absolutely not. I’m not being the medic. I’ll shoot you with my fake gun and now you’re dead.” Those kind of kid squabbles, but it was something important to me. Like, I don’t know why you’re asking me to be the medic, because there’s nothing about me that would imply that I should be. So I did gravitate more towards masculine things.

The other thing is, my grandmother used to make my clothes when I was a lot younger. And so I had very specific rules for what clothing she could make. It was: no frills, no sparkles, no sequins, no pink, later on, no purple, just nothing overtly feminine. Those were my solid rules. If she made it, I wouldn’t wear it. Or I’d wear it once or twice to be grateful, and then, it’d go to the back of my closet to rot there.

MW: When did you begin presenting fully as a boy?

GRIMM: I was dressing 100 percent male, barring when I was forced to do otherwise, since I was 11 or 12. My mother was still pushing for feminine clothing — it was mostly T-shirts, but anything beyond that was fairly androgynous. Even at that time, I can remember very vividly, I still had long hair, and the clothing I was wearing wasn’t from the boys’ section, and wasn’t overly feminine, but was clearly from the girls’ section. And some younger kids, like first- or second-graders, asked me if I was a boy or girl. Even though appearance-wise, I was feminine, I guess my mannerisms weren’t.

MW: Were you ever bullied or teased about that?

GRIMM: I was bullied and teased a lot. I don’t know that I’ve been specifically called out for having primarily male friends, and activities, or anything like that. But I did get called a “weirdo” daily. And I’m sure that had something to do with it, because I wasn’t socializing with the other girls, and I wasn’t interacting with them as my peers thought I should, because I was a girl, or at least occupying that social role at the time. I think people just didn’t know how to deal with me.

MW: Did you ever get comments from adults about not socializing with girls or anything like that?

GRIMM: I remember teachers would encourage me to do more typically feminine things. I used to read a lot, and I would go to the library looking for a book, and so many times, people would say, “Oh, we’ve got the girls’ section over here, and this book is about little Sally who picks flowers for her mom.” And I’d be like, “I’m not interested. I want a book that’s adventure.” I liked the Magic Treehouse books, because they were historical. And they’d be like, “But what about this book about Junie B. Jones?” It was really frustrating, because instead of listening to what my interests were, they tried to shove me in a different direction.

MW: When did you finally come out as a boy?

GRIMM: It was a long process. One of biggest troubles I had growing up was that I was raised religiously. And I was of the opinion that it was a thought crime that would damn me to hell for eternity, just to think outside of my assumed gender roles and expectations. I realized I liked girls. It was out of the context of “Everybody thinks I’m a girl, and I guess I am, so I guess that makes me gay.” And then it would be, “I just thought that, and now I’m going to hell.”

What happened was my mother cornered me. I had been in a really depressive funk for the past month or so, and that was manifesting as anger. I was lashing out and generally just unpleasant to be around. She corners me in my room and says, “I know why you’re acting this way. You’re a lesbian. Tell me.” And I was thinking, I either deny it and she gets mad at me, and I get in trouble for being a crappy person for the past month, or I say yes, and it’s my get-out-of-jail-free card, and then I can wear whatever I want, and maybe she’ll stop telling me to shave my legs. I thought it would work, but it didn’t. It was a momentary reprieve — my mood upped a bit for a couple of weeks, and then went back down. I didn’t know what was going on, but I knew that wasn’t the fit. It wasn’t the fix-all I expected it would be, and there was just something still wrong.

There was a period in middle school where I told my best friend. I said, “What if I wasn’t a girl? What if I was something else?” Because I’d seen it online, and I was newly introduced to the concept, and it was exciting to me. We would talk about it, and he didn’t really understand. He would move forward under the assumption that it was a hypothetical. But we’d go out, and my hair was cut short, wearing male clothing, and at the time I think I had also bought my first binder behind my parents’ back, so I was also binding my chest as well. I’d go out in public, and people would gender me correctly, and he’d correct them. And I was too embarrassed to tell him, “Don’t do that.” They’d say, “Sorry, sir.” “Have a good day, sir.” And he’d say: “He’s a girl.” Obviously, that was very upsetting to me, but he didn’t know at the time because I wasn’t very clear about it. But as soon as I came out, I told him firmly, “This is my name. You have to use it, exclusively male pronouns,” he switched over immediately. I don’t think he messed up once. He’s been great about that ever since.

MW: When did you finally assert yourself?

GRIMM: I think it was toward the end of middle school or the beginning of my freshman year in high school. But it was still a secret. He was the only person that knew until that point. And then I implied it to all my friends. After Christmas break or spring break, I didn’t come back, because the anxiety and the dysphoria and the depression was getting so bad that I couldn’t function in school. And then when I came back in the sophomore year, I had fully transitioned over the summer.

MW: Did you ever see a therapist?

GRIMM: I had a therapist who was awful. Just god-awful. This woman was not professional. I came out to her. First of all, the struggle with religion was very prevalent in my life at the time I was seeing her, and she refused to let me talk about it. She was very, very obviously religiously biased, and when you’re a therapist, you cannot let that influence your care. It wasn’t even a Christian place. It was not religiously oriented at all. She refused to let me speak. She’d stop me, and say, “You don’t have to explain yourself,” or say, “I get it.” She wouldn’t let me say it. I told her that I was transgender, and she just absolutely would not use correct gender pronouns. She’d tell me, “Well, since your mom doesn’t know, I can’t do that.” And I’d say, “That’s not on the books anywhere. I know that’s not a rule here.” But she was not supportive at all. At that point, I stopped seeing her. I just told my mom I didn’t like her. The next therapist I got was a gender therapist.

MW: And did that person help you?

GRIMM: Yeah, I didn’t need counseling at that point. I didn’t need counseling from her. What I needed was a letter to say, “Get this kid on hormones ASAP.” And that’s what I got. My dysphoria was so bad at that point — and it varies from doctor to doctor, most will see a kid a couple of times before writing a letter — but I got in there, and at the end of that first session, she was writing the letter. Which was all I needed from her. Because at that point, she was so far away from us, we had to drive so far to find a gender therapist, about an hour every time, to Richmond. It wasn’t feasible to see her for therapy when there are so many people close by, but she was the closest one that would have written any recommendation letter or anything like that, at the time. So she was helpful in that respect.

MW: So by the time you entered your sophomore year, you were identifying and presenting as male, and going to the school administrators and explaining your transition, correct?

GRIMM: Yes.

MW: What was the initial reaction?

GRIMM: My principal was awesome. He was so supportive. I went to him beforehand, and I told him, “This is what’s going on, and I’d like to make sure I’m respected here,” and to change my records and everything. And he said, “I assure you, in my school, you’re not going to get flak from teachers. And if any bullying should occur, it will not continue to occur if you report it.” I didn’t immediately ask to use the boys’ room, I actually asked to use the nurse’s restroom, because I was very fearful about how I’d be received. No incidents whatsoever. I was not received poorly at all. Well, I don’t want to say “not at all” — no one really teased me or anything about it. I got some confusion, but I mostly ignored that, and no one really called me names or anything like that. Just staring and whispering and whatever, but nothing to indicate to me that I should be scared to use the restroom. And so I went to my principal and said, “Can I use the [boys’] restroom?” And he said, “I don’t really have a reason to say no, so we’ll say yes and see how it goes.” Of course, it wasn’t just a unilateral decision, he talked to whoever was necessary. And he came back and said, “Feel free.” And for a period of seven weeks, that worked just fine.

MW: Who reported you?

GRIMM: The only thing I’ve heard is that a member of the community complained that a girl was in the boys’ room. It wasn’t apparent if they were a parent or not.

The first school board meeting, we were not even informed of, despite my being on the docket. We found out by chance through a friend of my mother’s, the night before. My mother stayed up all night, creating this information packet about the legality of things, and the mental health effects of barring a transgender youth from the bathroom. Basically, reasons why you should do the right thing. That got them to postpone the vote until December. Not a single person spoke for me, except for the people who came with me. I feel like, in our absence, they would have just voted then and there.

MW: How many people spoke on your behalf at the second meeting?

GRIMM: Well, the people who came with me, again. And one or two people spoke rather ambiguously. One or two spoke for me. And then hordes of people spoke against me, all saying virtually the same thing, including a security guard at my school, who — wouldn’t you know it? — was a pastor.

MW: What was their argument?

GRIMM: “We’re worried about your safety,” from a couple of them. The minority pretended to care about my safety. And then, quite a few of them were like, “If you’re a girl in the bathroom with boys, I know how I was when I was a young man.” Which is a rather disconcerting statement to make. So there was a lot of “He’ll get raped,” or, more specifically, “I know that boys are rapists,” which is a really ludicrous, blanket statement to make. It was painting all boys in the school as rapists. If you’ve got a rapist in the school, you’ve got bigger problems. It was really strange. The other arguments I heard were, “The boys don’t want a girl in there.” I have facial hair, so if they’re uncomfortable with someone like me in the restroom, they’ve got deeper-seated problems. And the other one was, “What if a boy goes into the girls’ room to molest women?” Which is really stupid. It was a slippery slope argument.

It’s not like I woke up one day, cut my hair, and said, “I’m going into the boys’ room.” It was a long process. I had a medical diagnosis. I had shown evidence of social transition for definitely longer than a year. I had my parents behind me, saying, “He’s a boy. Here’s the medical documentation. He’s about to be on hormones,” all that stuff. So it was very obvious that this had all been done in a very medical context, which is how it should be. No boy is going to be able to wake up, slap on a wig and a bow, and say “I’m a girl.” That’s not how it happens. Common sense would be that someone has to have a diagnosis. Somebody would obviously have to be socially transitioning for a while. And someone would probably have to be under the care of a therapist. And no boy that wants to molest a girl is going to be able to get a letter saying he’s a girl. And furthermore, he wouldn’t go through being a social outcast by being assumed to be a transgender girl in school, just so he can harass girls. That’s just not going to happen.

And furthermore, should anybody do that, whether transgender or not, they go to jail. I guess people think that if you’re transgender and do that, you get a get-out-of-jail-free card. That’s not what happens. If a transgender person were to do that, they’d go to jail, and not for being transgender, but for sexual misconduct, or whatever they did. So basically, their arguments are nonsensical fear-mongering, which don’t stand up to scrutiny.

MW: Have you received any unwanted attention locally, even since the resolution by the school board?

GRIMM: Yeah, I have received unwanted attention. I got stopped in Wal-Mart once, and Food Lion another time, and we went to Kiptopeke for a vacation, and someone stopped me in a restaurant there. They’ve all been positive, in every public interaction. And even last night, at the concert, it broke up and we were standing in the remnants of the crowd, and a guy came up to me and said, “I know who you are. Take a selfie with me.” And he added me on Facebook. And he turned out to be a fine guy, but you never know. It’s very positive, but I also think, “Oh, I just wanted to go to Wal-Mart,” or “I just wanted to take a vacation.” I’m glad they’re supportive, and it’s nice to know I have support in all corners, but I just don’t want to think about it sometimes. And then, of course, I get some pretty nasty messages on Facebook from time to time.

MW: From kids or adults?

GRIMM: From adults. I’ve never gotten one from a kid to date. Those honestly tickle me. I’ve never gotten one that hurts my feelings, they’re so pitiful. And a lot of them just make me laugh.

MW: Are they local adults, or from other states?

GRIMM: I haven’t checked into that. I respond to whatever they said, if I feel it’s worth a joke. And then I block them immediately, because I don’t have any intention of having a back-and-forth with these people. So I don’t know if they’re local. When you click on their profile and see where they live, I don’t recall ever seeing anyone local. They’re from New Jersey, and Florida, and Montreal. And I say it like there’s a whole bunch of people. I’ve gotten about 15 or 20 negative messages, over a couple hundred positive messages.

MW: What do they say, these adults?

GRIMM: Obviously, there’s the religious aspect in general. My Facebook is private aside from my profile icon and my header image. And my header image is a quote from Epicurus, and it says: “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?” It basically boils down to a bunch of contradictions that don’t make sense, so why believe in God. But it apparently is very inflammatory to a lot of people, who already come to my page, I assume, to be hateful. So they go to my page, and they’re already offended, and they see that I’m some heathen atop of heathen. And they get so angry. So I’ll get messages like, “Who do you think you are, denying God?” And I’ll say, “Who do you think you are, thinking some kid you don’t even know cares?” And then I’ll block them. I never call names. I don’t insult these people. I don’t care what they say to me, I’ll never do that. But sometimes you can’t help being a little sarcastic.

I got one the other day that said, “You’re a fucking homo asshole.” He was so angry, he was so mad. [Laughs.] And I blocked him. But that was funny. That one really got me laughing. I’ll get weird ones like that. But most of them boil down to “my deity doesn’t like you, and I know this for some reason, because I know what a deity thinks,” or “Hey, I’m going to talk about your genitals explicitly.” Like, “You have a vagina. Vagina, vagina, you, your vagina. Wrong bathroom.” Invasive, you’re talking about my genitals kind of stuff.

MW: How many supportive messages have you gotten?

GRIMM: Definitely in the hundreds. I try my hardest to reply to all of them, but I get so many. And I feel so bad, because I appreciate every single one of them. I feel like people go out of their way to say something supportive to me, and try to make my situation just a bit better. I just hope they don’t take it personally that it takes me so long to get back to them. But I do try my hardest to get back to everyone eventually, even if that’s eight months later.

MW: When we talk about Youth Pride, what is it that LGBT youth have to be proud of nowadays?

GRIMM: I guess I’m not the best person to ask that, because I’m not proud of being trans. I hate being trans. I would give anything not to be trans. It’s caused me so much pain, and I will always, always have dysphoria, and I will always have to consider my trans status as a part of my daily living. I can get every surgery in the world, and I can still not father children. And there are certain things that will never be how I imagine my body to be, and function as it functions. So I don’t have pride by virtue of how I was born.

But I guess where my pride would lie is in having the courage to be myself. And with any other LGBT youth, to have the courage to be themselves, and live authentically, in a world that maybe isn’t very kind to them. And having the courage to stand up for others as well. That’s where the pride should lay. Not on a situation they can’t control, but how they handle that situation. Pride should come from their actions in accepting themselves and being able to be who they are.

MW: Recently, there was an ad put out by Trans United Fund, showing the stories of parents of transgender children. Is that an effective way to educate people on the issue?

GRIMM: I don’t think I’ve seen the ad. However, if it’s about what it’s like to be the parent of a transgender child, and the decision of what to do to help your kid, I think that can absolutely be effective. Maybe if people saw these parents saying, “This was the best thing for my child. My child was suffering, and now my child is happy.” If they heard that narrative, and heard from adults saying this is very real and the best way to help your kid is to accept them and let them be who they are, maybe that can change a lot of minds, and help a lot of future kids as well.

MW: What would your advice be to a younger person experiencing gender dysphoria, who doesn’t have the vocabulary yet to explain that?

GRIMM: I would say, first of all, be careful. Because if you express these feelings to the wrong person, you could end up being a lot more alone and a lot more scared than you were previously. I, however, would also say that it’s normal, and that it’s nothing to be ashamed of. I’d also give them the word: transgender.

So when it’s safe, tell people. And if it’s not, just find little things to do for yourself that can make you love yourself.

If you are a transgender youth and are in need of resources, visit the Trans Youth Equality Foundation at transyouthequality.org or send an email to contact@transyouthequality.org.

Support Metro Weekly’s Journalism

These are challenging times for news organizations. And yet it’s crucial we stay active and provide vital resources and information to both our local readers and the world. So won’t you please take a moment and consider supporting Metro Weekly with a membership? For as little as $5 a month, you can help ensure Metro Weekly magazine and MetroWeekly.com remain free, viable resources as we provide the best, most diverse, culturally-resonant LGBTQ coverage in both the D.C. region and around the world. Memberships come with exclusive perks and discounts, your own personal digital delivery of each week’s magazine (and an archive), access to our Member's Lounge when it launches this fall, and exclusive members-only items like Metro Weekly Membership Mugs and Tote Bags! Check out all our membership levels here and please join us today!

You must be logged in to post a comment.